The history of the looting of the Parthenon sculptures is complex and controversial. Contrary to claims that a Sultan’s firman authorized Elgin, no such document has been found. Instead, a disputed license from the kaymakam Seged Abdullah has surfaced, raising questions about its legitimacy. The full text of this license, its contentious wording, and valuable insights from Adolf Michaelis’ book “Der Parthenon” shed light on this historical episode.

The Controversial Parthenon Sculptures

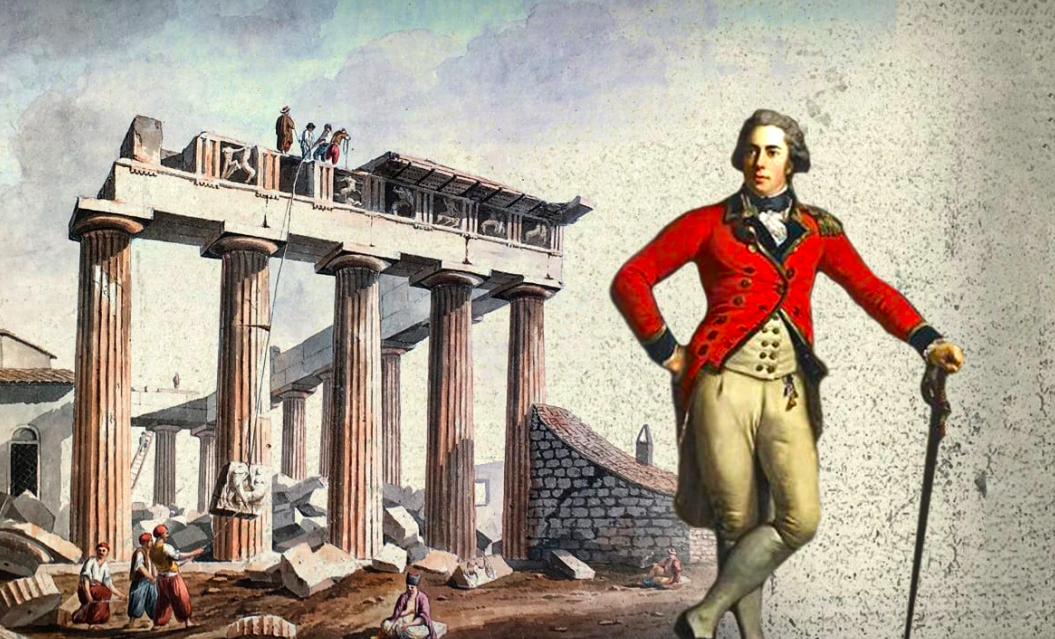

The Parthenon Sculptures, stolen by Scottish Lord Elgin over 200 years ago and now housed in the British Museum, have resurfaced in the news. Turkish archaeologist Zeynep Boz, speaking at UNESCO’s 24th Session of the Intergovernmental Commission on the Return of Cultural Property, stated that no legal document exists for Elgin’s acquisition—more accurately, seizure—of these sculptures. Boz revealed that her team, along with other Turkish archaeologists, found no firman in Ottoman archives authorizing Elgin to remove the Parthenon Marbles. The British have long cited a firman translated into Italian, the authenticity of which remains disputed.

A Deeper Investigation

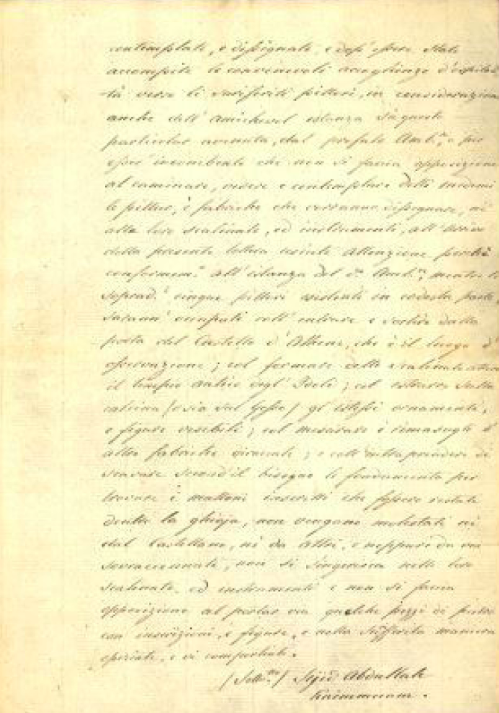

Given our interest in the Parthenon Sculptures, we decided to investigate thoroughly. We referred to Kyriakos Simopoulos’ classic work, “Foreign Travelers in Greece 1800-1810,” Volume C1 (PIROGA Publications), and Antonios Miliarakis’ significant work, “About the Elginian Marbles” (1st Edition 1888, 2nd Edition 1994), which provided valuable information. Additionally, we examined Adolf Michaelis’ “Der Parthenon,” published in Leipzig in 1870-1871, available online in German. This work includes the purported firman given to Elgin on page 355.

Miliarakis, who translated the license, noted it is not a firman (which should bear the Sultan’s seal and signature) but rather a license from a kaymakam a senior Ottoman official. This license, translated into Italian and later into English, does not grant Elgin permission to take pieces of the Parthenon.

Clarifying Misconceptions

There is no firman, as it would have required the Sultan’s seal and signature. Nor did the Grand Vizier provide Elgin with any document, as he was absent in Egypt at the time. The kaymakam who issued the license was a high-ranking official, though her exact position is unclear. The document was included in Michaelis’ “Der Parthenon,” translated into English, and cited by Miliarakis with the help of an English expert. We republish this information today for our readers.

The License Controversy

How did Elgin obtain this contentious license? Thomas Bruce, 7th Earl of Elgin, was a British diplomat born in 1766 in Broomhall House, Scotland. He received an extensive education and was deeply interested in archaeology and ancient art. He served as the UK ambassador to Austria (1792), Prussia (1795), and the Sublime Porte (1799). During the mid-18th century, archaeological books on Athenian antiquities began circulating in Europe, spurred by depictions by Stewart (1748) and Revet (1754).

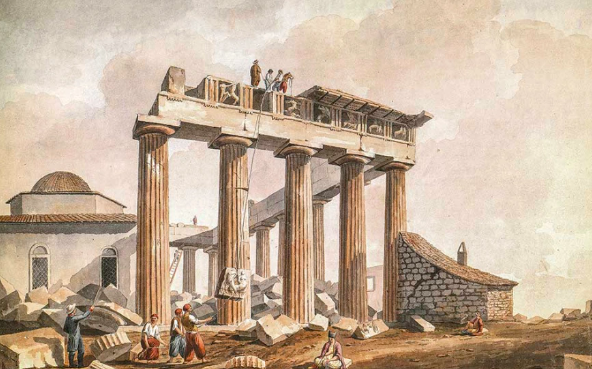

Only the eastern part of the Parthenon remained intact, with various reliefs removed from other sides. Chateaubriand noted in his travelogue that the English could not accurately depict the clean lines of Phidias’ works from the 5th century BC, indicating the skill gap in the 18th century.

Conclusion

While in Constantinople, Elgin discussed the importance of ancient monuments with architect Thomas Harrison. The legitimacy of Elgin’s actions remains contested, and the absence of a proper firman underscores the controversial nature of the Parthenon sculptures’ removal. This exploration, drawing from historical texts and modern investigations, invites readers to form their conclusions about this enduring cultural dispute.

Ask me anything

Explore related questions