If there was a malevolent demon in the modern history of the Cyprus issue, it is the junta. Despite their patriotic rhetoric and grand statements, the colonels proved to be “insufficient” both as military officers and as rulers.

The first move to defensively strip Cyprus was the withdrawal of the Greek division that had been secretly sent in the early 1960s after the Turkish uprising of 1963-64. The final blow was the coup against Makarios on July 15, 1974, which became the pretext for the Turkish invasion and the 50 years of occupation of 37% of the territory of the Republic of Cyprus. These 50 years during which the occupation turned into Turkification and the prospect of a solution seems to remain an unfulfilled expectation.

Weeks before the coup on July 15, 1974, everyone was talking about the planned overthrow of Makarios, as the conditions in Cyprus were, to say the least, abnormal. Archbishop and President Makarios, in his efforts to counter the illegal activities of EOKA B’, which was created by General Grivas who had secretly arrived on the island, encouraged the formation of paramilitary armed groups.

Grivas died in Limassol, but EOKA B’ was not dissolved. Control of it was taken over by Ioannidis’ junta along with Greek officers serving in the National Guard of Cyprus and Cypriots who harbored a deadly hatred for the “priest.”

Having survived several assassination attempts and destabilization efforts by EOKA B’ to overthrow him, Makarios was convinced that Ioannidis would not dare to stage a coup, knowing what would follow. Even at that time, Makarios credited the junta with a minimum of rationality and patriotism, believing that the confrontation was solely about him.

On July 5, 1974, after sending his well-known letter to president General Gizikis in Athens, he held a press conference and was asked if he feared a coup. Makarios seemed to be unaware of the danger and replied, “I give no importance to the coup reports. In my opinion, there is no possibility of a coup. But even in the event of a coup, there is no prospect of success.”

It turned out that he was wrong in everything, naively again facing the real dangers.

The escalation of tensions in the relations between Makarios and the junta was also related to Makarios’ turn towards the Soviet Union, which caused concern in NATO, the USA, and the guarantor powers (Greece, Turkey, and the UK), which were NATO members.

At the height of the Cold War, Makarios chose to visit Moscow in June 1971, and a year later he proceeded with the secret importation of weapons from Czechoslovakia, which was a member of the Warsaw Pact.

While Makarios’ rift with the junta regime in Athens was complete, it reached its peak with Ioannidis’ interventions in the National Guard of Cyprus. Makarios decided to reduce military service to 14 months, and removed from the list of candidate officers those who were sympathetic to EOKA B’ and the junta. He also demanded the withdrawal of most of the Greek Army officers from Cyprus.

On July 2, 1974, through the Cypriot ambassador to Athens, Nikos Kranidiotis (father of Giannos Kranidiotis), Makarios sent his well-known letter to Gizikis. The letter was considered -and indeed was-hostile and confirmed the junta’s “correct” decision to overthrow him with a coup.

The letter from Makarios to Gizikis was not the trigger for the decision to stage the coup. The decision had already been made by Ioannidis and was known to Gizikis, prime minister Androutsopoulos, and Chief of the General Staff of National Defense, General Bonanos.

The operation was undertaken, at the operational level, by the Commando Forces led by Brigadier Kompoki and Colonel Georgitsis.

From what has become known so far, those who knew the coup plan were few. For this reason, before July 15, the Chief of the National Guard Lieutenant General Denisis, the Commander of ELDYK Colonel Nikolaidis, and the Director of the 2nd Staff Office of the National Guard (Intelligence) Lieutenant Colonel Bourlos, were called to Athens for meetings at the General Staff of National Defense. All were kept in Athens on Bonanos’ instructions so they would not be in Cyprus on July 15.

“Makarios is dead,” “you recognize the voice you hear.” These two statements could sum up everything that happened on July 15, 1974. Two statements that traveled over the airwaves of the junta-controlled RIK and the free radio station of Paphos. It was the technology of the time that had its place in history. To this day, the events of the coup overshadow the political life of Cyprus and are an integral part of the tragic picture composed of the Turkish invasion and occupation of 37% of the territory of the Republic of Cyprus for half a century.

What happened at 8:15 on July 15, 1974, is well known, and the sirens that tear through the skies of the free areas with their chilling sound remind us of it every year.

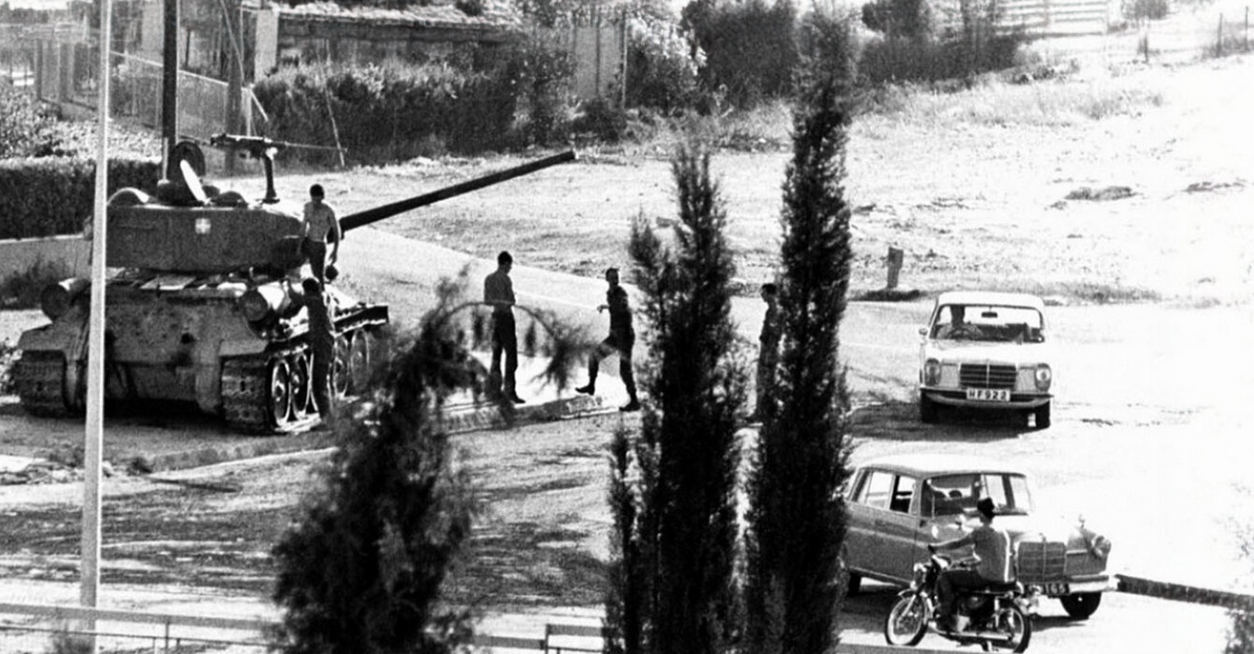

The coded signal sent to the forces involved in the coup stated: “Alexander entered the clinic.” Tanks entered the Presidential Palace while Makarios was receiving Greek children from Egypt.

“This morning, the National Guard intervened to stop the fratricidal war among Greeks. The National Guard is currently in control of the situation. Makarios is dead.” With this simple, repeated announcement from the studios of RIK radio, the coup plotters informed the public of the crime, which would be completed five days later with the Turkish invasion.

The “dead” Makarios heard the announcement of his death while heading to Paphos, having managed to escape the murderous gunfire of the coup plotters at the Presidential Palace through a window in his office. By spreading the news that Makarios was dead, the coup plotters boastfully signed off on their crime. After all, Ioannidis had given clear instructions to “President” N. Samson. He had said, “Nikolakis, I want the head of Mouskos” (Makarios’ surname).

And while the coup seemed to be establishing itself, a faint voice, muddled in the fog of the radio waves’ buzz, changed the grim picture and opened a window to illuminate the darkness that had covered the island early on that Monday morning. Makarios, having hastily written a text on a piece of paper, kept the resistance alive from Paphos. The surviving handwritten document has become a historical record of a story whose end we do not yet know. Makarios’ broadcast from the free radio station of Paphos is well-known to everyone. However, one interesting sentence, written by the President and Archbishop himself and then crossed out, suggests that he did not want to give the impression of personalizing the responsibility or attributing it to the junta’s puppet, Nikos Sampson.

Shortly before the end of the speech, Makarios’ handwritten draft included the sentence: “I regret that there was even a ridiculous figure named Sampson, and the junta appointed him president.” This sentence was bracketed and crossed out with an “X” by Makarios himself. Although it was not broadcast over the radio, it is a historical element showing the Archbishop’s view of the junta’s choice to install a willing collaborator of minimal to non-existent seriousness in the “presidential seat.” An indicative incident was recounted to the author by veteran journalist Panagiotis Papadimitris, highlighting Sampson’s seriousness and understanding of the gravity of the crime he had committed. “He complained,” Papadimitris said, “because he was called the eight-day president, arguing passionately that he remained in ‘power’ for nine days and therefore should be called the nine-day president!”

The coup of July 15, 1974, did not come out of the blue. It was preceded by a series of events, including an ecclesiastical coup organized by the junta with Grivas’ involvement. The demand made by three Cypriot Metropolitans in 1972 for Makarios to resign from the presidential office led to the dethronement of then-Metropolitan of Paphos Gennadios by clergy and laity. However, Gennadios remained Metropolitan, having taken refuge in Limassol. On April 3, 1972, he sent a letter to Archbishop Makarios, openly threatening him by stating that he was receiving urgent recommendations for his immediate return to the Metropolis of Paphos “under the responsibility and protection of others, equally or more powerful and determined than the political supporters of Your Beatitude. (…) I wonder, however, how long I can restrain the wrath of national fighters, who are ready to liberate the Metropolis of Paphos from the invaders and to put the entire province in order…”.

In response to Gennadios’ letter, Makarios made two handwritten notes. In the first, he wrote: “Returned. The content is unacceptable.” In the other note, he commented: “Much hypocrisy and cunning characterize the content of the letter.”

From the tone of Gennadios’ letter and Makarios’ comments, it is clear that as early as 1972, the situation had started to become dangerous, with a metropolitan openly threatening intervention by national fighters (EOKA B) to remove control of the Metropolis of Paphos and the entire province from the Archbishop and President.

The conflict between the Archbishop and the Metropolitans of Paphos, Limassol, and Kition was the first spark of the clash with the conspirators. The situation escalated with the illegal dethronement of Makarios and eventually the removal of the three Metropolitans by the Major and Superior Synod convened by the Archbishop after his re-election to the presidency of the state.

Ask me anything

Explore related questions