The Bektashi sect (Bektaşi) of dervishes belongs to Sufi Islam and represents an important chapter in the history of Islam in the Middle East, Asia Minor, and the Balkans during the Ottoman period. It is a blend of Muslim faith, Christian Orthodox monasticism, and Masonic mysticism. The followers of this sect are monogamous, eat pork, and drink alcohol.

The Bektashis in Islam are akin to the Knights Templar in Christianity; that is, a heretical, mystical order with a hierarchical structure, unique architectural temples, and economic power. For centuries, the Bektashi order exploited the lucrative salt mines of the Ottoman Empire, with the salt from those mines being known as Hacı Bektas.

The Sect of the Poor and Farmers

The Bektashis, along with the Mevlevi and Nakshbandi, are considered the most well-known branches of Sufism during the Ottoman Empire. While the Mevlevi and Nakshbandi had more influence over urban classes of artisans, merchants, and nobility, the Bektashi resonated more with the poorer social strata of villages and communities within the Empire, consisting mainly of farmers and herders.

The ideas of the Bektashis are linked to the liberal thought of 18th-century philosophers in France. They had connections with one of the networks that promoted the ideas of these philosophers: Freemasonry. Many active politicians in Istanbul were connected in one way or another with Freemasons during the 19th century, a period when French and English lodges were established in the city. The membership of these lodges increased toward the end of the 19th century, leading to the emergence of a group of opponents to Sultan Abdul Hamid II (1876-1909), known as the “Young Turks.”

The Founder and His Worldview

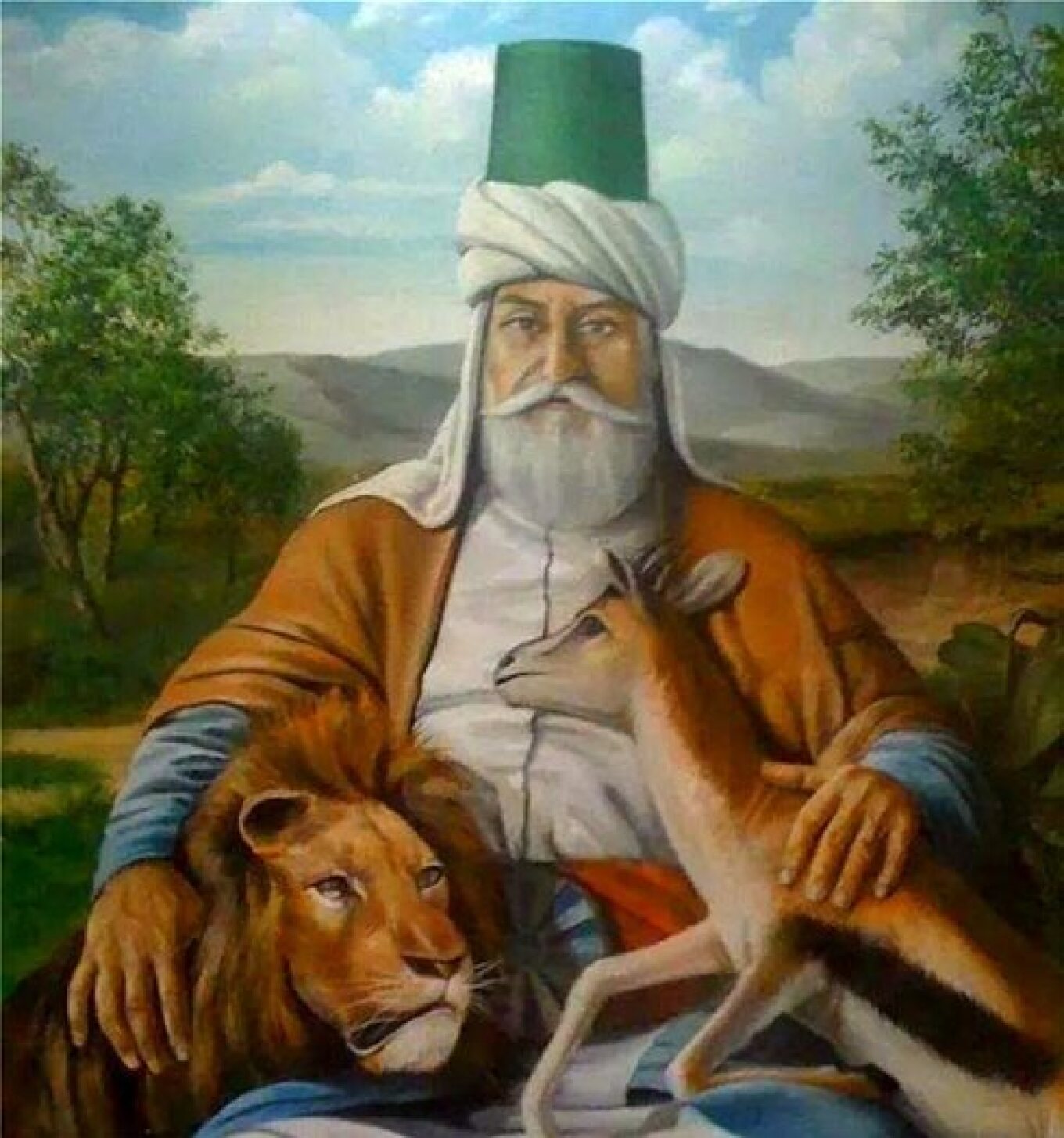

The founder of the sect is considered to be Hacı Bektaş Veli, a wandering dervish who lived in the 13th century CE. Little is known about his life, and some scholars have even argued that he may not have been a historical figure.

His worldview contrasted with orthodox Muslim doctrine, which promoted a rigid and puritanical religious law that all were expected to follow blindly. The Brotherhood envisioned by Hacı Bektaş was based on an anti-hierarchical understanding of religion, where humanity would be at the center.

Mysticism

The Bektashis rooted themselves in the popular layers of the Ottoman Empire. At the core of their ideology lies Islam. However, their ideology encompasses all currents of Ottoman history, the customs and traditions arising from the national lives of various peoples intertwined through the shifting borders of the 13th century. From this mixture developed a folk religion aimed at establishing a direct connection between humans and the knowledge of God.

The Bektashis do not have any public worship practices. In fact, the entire ritual of the Bektashi order is shrouded in absolute secrecy, fueling significant curiosity among researchers. Furthermore, when considering their beliefs regarding women’s freedom and the rejection of fanaticism among religious leaders, it is no surprise that they were officially abolished by the Turkish Republic within the borders of the national state.

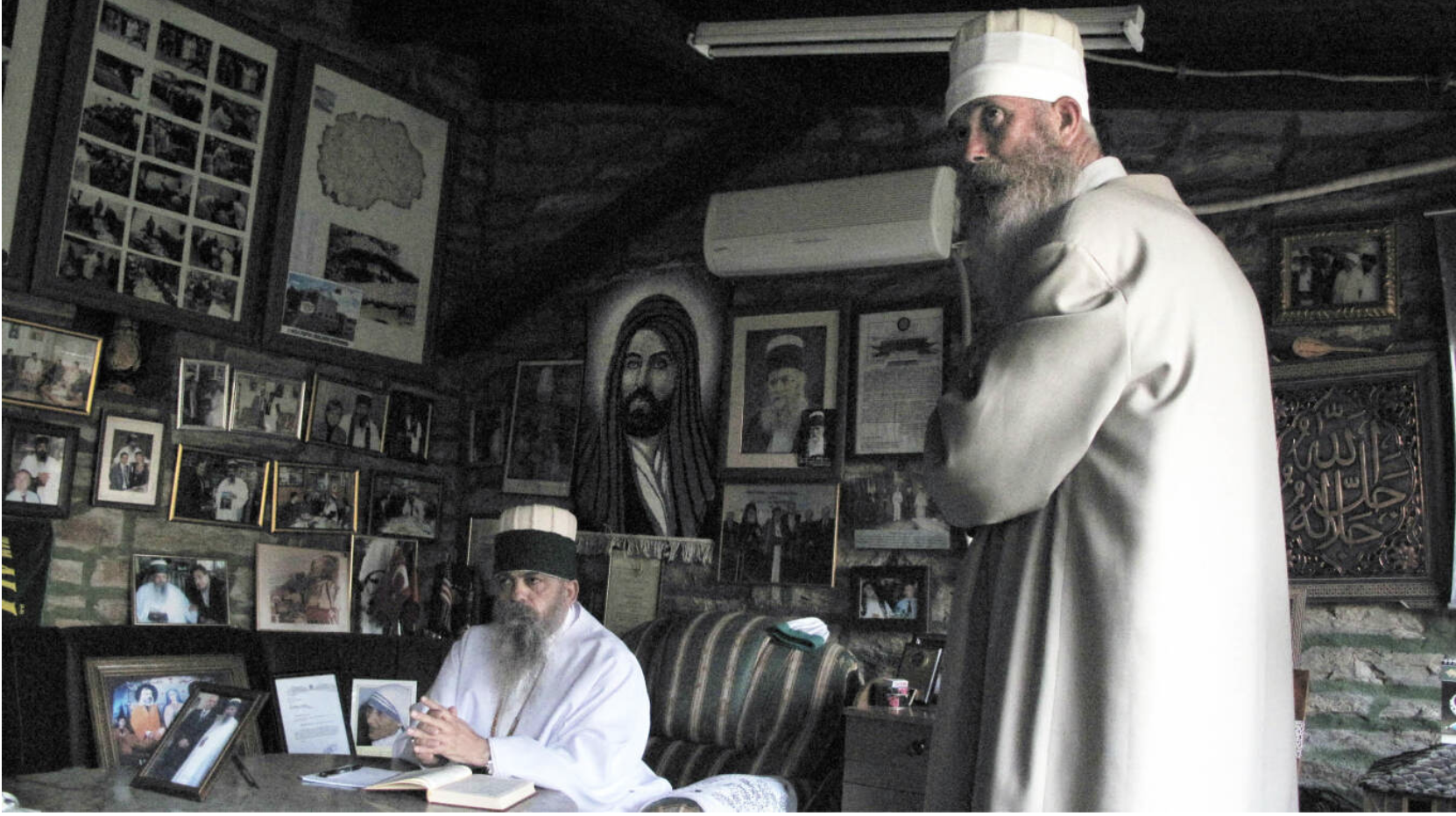

The Clergy

According to sources, the members of the order are divided into six main categories: the Aşik, connected members who have not been initiated, and the muhib, or initiated Aşik who have the right to participate in certain Bektashi rituals. Next are the Dervishes, who take an oath, gain skills in practicing the Path, and have permission to wear the ritual garments and insignia of the Bektashis. Following them are the Baba, who direct the local tekke and lead local communities. They essentially oversee the Dervishes, Ahi, and Aşik.

At the highest levels of the hierarchy are the Munjarad Dervishes, who take a vow of celibacy and are initiated into a secret ritual. They live solely in the tekke, shave their mustaches and beards, and wear a silver earring in the right ear as a symbol of their position. At the top of the hierarchy are the Khalifa, heads of regional tekke, some appointed by the head of the Dede-Baba seat.

The Downfall

In 1789, Selim III, a descendant of Mehmed II, ascended to the throne. Sensing the threat posed to his power by the highly conservative Janissary order, he believed that the survival of the Ottoman Empire was directly dependent on suppressing them, as well as the Bektashi order. It is said that Selim swore to behead 70,000 Bektashis, and when he could not find that many to execute, he ordered their heads to be cut off and counted until the number was reached!

The Bektashis in Albania

The ideology of the Bektashis spread to Albania from the island of Corfu by the Dervish Sarı Saltık toward the end of the 15th century. He established seven tekkes, including one in the mountains above Krujë, where legend has it that he killed a dragon. The sect grew throughout the country, except in areas that had embraced Catholicism in the north. It is worth noting that the repression by Mehmet II is also connected to the fact that Ali Pasha Tepelena, the warlord of Epirus, belonged to the Bektashi sect.

Many of the leaders of Albanian nationalism were Bektashis, and the order shaped the “left” wing of the Islamic spectrum in the Balkans. After the destruction of the Janissary corps in 1826, many Baba and ordinary Bektashi dervishes scattered to remote areas of the Balkans, away from the reach of the Ottoman government. During this period—especially after the annulment of the proscription of the Bektashis in 1860—the order significantly expanded its presence in southern Albania.

During the Ottoman rule, particularly after the Russo-Turkish War of 1877-78, as the Ottoman Empire was in a state of disintegration, the Albanian separatist movement emerged. To control the situation, the Ottomans attempted to impose the Turkish language on Albanians as well as on the Pomaks.

In response, Albanians formed secret communities in neighboring Balkan countries and secretly established schools for primary education in the Albanian language. The Bektashi order contributed to the maintenance of the Albanian language by operating clandestine schools during the late Ottoman period. In 1902, Sultan Abdul Hamid ordered the closure of schools and the prohibition of books in the Albanian language. At that time, the tekkes of the Bektashis formed a network of illegal schools where educated dervishes preserved the national culture of the Albanians.

In 1922, an assembly of representatives from all the tekkes of Albania separated the Bektashis’ relationship with the Supreme Bektashi, who had settled in the new capital of Ankara, before the order was suppressed by Mustafa Kemal Atatürk. Tirana became the headquarters of the order, and in 1929 it was recognized as an autonomous Muslim order, with a new statute.

In Greece

A Bektashi monastery (tekke) named Ireni Tekke existed until a few decades ago near the village of Asprogeia, Farsala, in Thessaly, where Albanian Bektashis used to reside.

Near the village of Roussa in Evros is the Tekke of Seyyid Ali Sultan. Approximately 3,500 Greek Muslims follow the mystical order in Greece. They are mainly concentrated in ten villages around Roussa, where the famous tekke of Seyyid Ali Sultan (Kızıl Deli) is located. Seyyid Ali Sultan arrived in Thrace in 1354 and established his tekke outside Roussa. He was the first representative of Bektashism in the Balkans, and his tekke is the second most significant sacred site for the Bektashis globally, after that of Hacı Bektaş Veli in Anatolia.

The Greek community’s outreach began recently with the first international symposium on Alevism—Bektashism in Greece, titled “Bektashis and Alevis in the Balkans and the East.” It was organized by the MOHA Research Center at the “Imaret” hotel in Kavala, which was built between 1817-1821 and functioned as a religious, educational, and charitable institution. In recent years, it has operated as a hotel.

For the Greek Alevi Bektashis, the position of women is equal to that of men. They drink alcohol, eat pork, and pray side by side, men and women. Polygamy is not allowed, and women are free to decide whom to marry.

At the symposium, which took place from November 3 to 5, 2023, Greek and foreign professors participated, including Konstantinos Tsitselikis, who teaches at the Department of Balkan, Slavic, and Eastern Studies at the University of Macedonia, and Heath Lowry, a professor of Ottoman and Modern Turkish Studies at Princeton University, as well as members of the Bektashi community of Thrace.

The researcher, journalist, and author Vangelis Aretaios, speaking to the Athens-Macedonian News Agency regarding the conference, emphasized that “the aim of this special gathering of people was to make the existence of the community more widely known while simultaneously highlighting the unique role they played in the region.”

“The Alevis—Bektashis are an integral part of the cultural identity of Thrace and have historical significance, as they have been in the region since the 14th century,” Aretaios stresses, adding: “From both an anthropological and religious studies perspective, this community is significant because its members maintain traditions that tend to be lost in many places. In Greece, we have a very vibrant Alevism, with people who keep alive customs, traditions, and spirituality of centuries that in other regions of the Balkans, where similar communities exist, are on the verge of fading or being reshaped, thus altering the culture and tradition.”

Approximately 3,500 Alevi—Bektashi Muslims currently live in the broader area of mountainous Roussa, in the municipality of Soufli, distributed across ten major villages (Goniko, Mega Derio, Mesimeri, Petrolofos, Myrtisiki, Chloi, Sidiro, Mikraki, Kisos). “These communities,” Aretaios emphasizes, “have one of the oldest organizations in the field of Alevism both in Turkey and in the southern Balkans. They consist of extended families that form an ‘ocağ’ as they are called in Turkish. In each village, there are one or two large families, from which the structure of the pyramid begins. Each ocağ has its own place of worship (cem-evi), and there is a council comprising all the ocağ from the villages that manages communal affairs. It is an entirely authentic organization of society, where they preserve intact the hierarchy of the extended family, which today is not found elsewhere to this extent.”

Ask me anything

Explore related questions