For 20 years now, PASOK’s internal party ballots have been hailed as a great celebration of democracy and mass popular participation. They are celebrated as a genuine expression of citizens taking the business of electing leadership into their own hands, a fact that is celebrated as proof of the party’s vitality. However, of the six presidents of the Movement to date in a political journey of half a century, only four have been elected by open ballot with the participation of party members and friends alike.

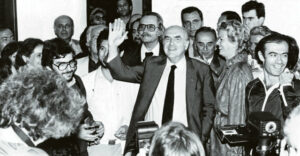

No party leader is eternal, indestructible, everlasting. On January 15, 1996, the historic founder and natural leader of PASOK as well as the country’s prime minister was hospitalized in deteriorating health at the Onassis Hospital. He had been there since 20 November 1995, after being rushed to hospital with respiratory problems. Almost two months later, on that chilly Gena Monday, the excitement in the “tent” in the hospital’s courtyard, crowded with journalists, was beyond the limits of frenzy.

In all the corridors and floors of the building the agitation of the patient’s first-degree relatives – his current wife Dimitra Liani-Papandreou on the second floor lobby and his former wife Margarita Papandreou with their children on the sixth floor – is reaching a peak. Likewise, the agitation of the crowd of party, government and state officials crowding into the sanatorium is intensifying to the point of breaking point. At the same time, channels, radios and newspapers – the Internet is in its infancy – are on alert.

Papandreou’s resignation

Developments are racing along without anyone being able to stop them. At 8pm, the surgery-weakened, weak Andreas Papandreou signs his resignation letter on the first floor of the cardiac surgery center. He addresses it to the Parliamentary Group and the Central Committee of the Movement. The 265 words of the written text are about to turn the page on PASOK and the governance of the country. The thriller for the succession of PASOK’s undisputed president of 22 years is about to begin as a matter of urgency.

The spotlight is now on Akis Tsochatzopoulos, who during Andreas’ hospitalization is temporarily acting as prime minister and representing the government at EU summits, as well as on Costas Simitis, who is fighting political battles in parliament over the budget. Three days later, on 18 January, the ruling party’s parliamentary group convenes to elect a new prime minister. The candidates in the elections are initially four: Akis Tsochatzopoulos, Gerasimos Arsenis, Kostas Simitis and Yannis Charalampopoulos. In the first vote, Simitis and Tsochatzopoulos are tied with 53 votes, while Arsenis with 50 votes and Charalampopoulos with 11 are eliminated from the race.

In the afternoon of the same day, a second vote takes place. The derby is a tough one. In the end, Costas Simitis is elected with 86 votes against 75 for Akis Tsochatzopoulos on the day of his feast day, St. Athanasius. Five members of the Parliamentary Group voted no. Simitis, one of the founding members of PASOK in 1974 and a minister in almost every government formed by Andreas Papandreou, is now the country’s prime minister. He is supported by the informal but powerful internal party “Group of 4”, which he forms together with Vaso Papandreou, Theodoros Pangalos and Paraskevas Avgerinos. And of course he has been supported in the second round by George Papandreou and Costas Laliotis. The next step for the Panteion professor is to be elected president of PASOK.

Meanwhile, at dawn (01.30) on Sunday 23 June 1996, Andreas Papandreou dies at the age of 77 after an acute ischemic attack at his home in Ekali. His close associates have previously drafted the text of his short speech-intervention at the party congress, which will take place a few days later. But he does not have time to approve it. And so it is never made public.

Turbulent conference

A week later, on June 30, the tumultuous 4th PASOK Congress convenes in a hall in the OAKA. In his address to the delegates, Simitis poses the dilemma of “either become president or resign as prime minister”. Blackmail works effectively. PASOK, which was electorally victorious at the time, has an astonishing instinct for self-preservation. Who is in the mood for populist adventures when the country is preparing for joining the EMU and organising the Olympic Games? The continuity in governability is guaranteed by Simitis.

Who was elected president at that congress with a percentage of about 53%, having again been opposed by Akis Tsochatzopoulos. It is on the day of the Holy Apostles, Akis’ other name. PASOK will be bathing in the latter’s hair a few years later. In any case, however, on those moons the modernist era of Simitis was inaugurated, with a record of eight years and two months in office. His departure from the presidency of PASOK puts a definitive end to the election of the party leader by the top party organs.

The “ring” to George

He quit the party presidency before the March 2004 national elections in order to avoid the upcoming defeat in the election battle. PASOK’s pre-election slogans of “party, party on March 7” are encouraging, as ashes to the eyes, to its loyal voters, as all polls detect, if not point with certainty, a triumph for Kostas Karamanlis’ New Democracy. Faced with the impending electoral debacle on that rainy night of Epiphany on January 6, 2004, Costas Simitis meets George, Foreign Minister and son of Andreas, to whom he hands over the succession ring.

This handover-receipt procedure raises many questions about its democratic nature. It is reminiscent of the cashing of old bills. Nevertheless, it passes without objections within the walls of the party’s HQ. George’s heavy surname, his good international image and his moderate style have helped him to achieve high popularity. So he also offers scattered hopes for the re-election of PASOK under his leadership. But these expectations will not be confirmed.

However, he is taking care beforehand to legitimize to the people that glittering ring he received, which will later appear dull to him. He rushes to its approval by the people, initiating, unprecedented in the usual party mores, a pioneering process. On 8 February 2004, he was the only candidate to run unopposed for the presidency of PASOK in an open vote of party members and friends alike.

More than 1 million people go to the polls – an extraordinary number – and George Papandreou gets 99.70% of the votes counted. Mass popular ratification of confidence in a candidate is now sufficient for his or her emergence as party leader. The innovative move he is introducing into the political scene will soon be emulated in an exemplary manner by the other parties of the democratic arc. The political map is changing with the release of each leader from the party infill.

This representative public crash test will also be faced by George Papandreou. In the autumn of 2007, immediately after his second consecutive defeat in the national elections by Kostas Karamanlis, the head of PASOK was severely challenged. Evangelos Venizelos, with the support of a number of party members, is boldly raising the issue of leadership. Before the votes in the country have been counted, he suddenly appears in the morning of 17 September 2007 at the Zappeion building.

Open questioning

From there, in an intercom, he throws down the gauntlet to George Papandreou by claiming the leadership of the Movement. The PASOK president picks it up.

The clash for definitive party supremacy begins. The conflict projects itself mercilessly. And it involves blunders.

After a series of misguided communication manoeuvres by the impulsive Venizelos and because of his overconfidence as a favourite instead of direct elections – the iron sticks to the boil – he is subjected to a two-month internal party campaign. During this period, hatreds, passions, quarrels, personal anger and plenty of conspiracy theories flare up, igniting an explosive climate of factionalism and division. With victory discounted, as he thinks, Venizelos plays it cool and often arrogant. For his part, the pending deposed Papandreou is addressing – in his “father’s name” – the traditional PASOK, declaring war in general on the “interests” that want to bring him down. Gradually he is gaining valuable points.

More than 750,000 voters turn up at the “green” polls on 11 November 2007. Papandreou is re-elected in the first round with 55.91% of the votes against Venizelos, who is second with 38.18% and Kostas Skandalidis, who is third with 5.74%. Papandreism, with deep roots in the country’s political history, is proving to be unbeatable. The mass popular choice of the son and grandson of the leaders of the democratic party means the beginning of the countdown for the prime ministership. To his credit, the brilliant but brilliant Venizelos with his professorial stature does not even attempt to split the party and supports its unity.

PASOK would triumph two years later, in the October 2009 elections, with 43.92% of the vote. The sleek, fit and technofreak Papandreou comes fired up to “change everything”. However, PASOK will be tested in the future by the accumulated fragments and fragmentary bits and pieces of the actual mosaic of that intra-party rivalry. At the end of October 2011, the troubles in the Papandreou government lead it to a deadlock. Bankruptcy, first memorandum, troika. Harsh austerity measures and crippling cuts make the situation worse. The debt crisis is rightly attributed rather to the previous five-year Karamanlis administration that had made a mess of things, but discontent in society is growing.

George Papandreou and Evangelos Venizelos fought a tough battle for the leadership at a time when PASOK’s ratings went from peak to trough and the country was under memoranda

The referendum and the resignation

George Papandreou, under pressure, retrieves lines from Cavafy and argues that “citizens must say the big yes or the big no”. He has proposed a referendum to approve or reject the EU summit decision. which, among other things, provides for a 10-year fiscal adjustment program, the creation of a permanent surveillance mechanism for Greece and an additional €130 billion aid package.

Papandreou is squeezed by both internal party opposition and the common attitude of the partners towards his initiative, which he eventually withdraws. On Sunday, November 6, he meets with the president of the opposition Antonis Samaras at the Presidential Palace, before President Karolos Papoulias. There the two political leaders agree to form a coalition government under Loukas Papademos.

Inevitably Papandreou resigns as Prime Minister, burdened with the mistakes, omissions and regressions of his administration during the country’s fiscal derailment. Despite the suggestions of his close associates, he will also delay resigning from the leadership of PASOK. He will do so a few months later. When the internal party recognition and respect for him has swept the bottom of his once popularity.

It is March 2012 when he decides to retire from the top post of PASOK as well, waiting for events to justify his future assessments, judgments and choices. The position of president is re-claimed, after almost five years, by the exuberant Evangelos Venizelos. He no longer has an opponent. On 18 March 2012, PASOK holds internal party elections to elect a new leader.

The time of Venizelos

More than 235,000 party members and friends of the party go to the polls. Venizelos is elected as the sole candidate with 97.44%. However, PASOK is now being bled dry by cadres who are adventurously looking for a flag of opportunity, and as a result it is shrinking electorally. In the May-June double elections of that year, it ranked third, having lost more than 30 percentage points from the previous victorious elections.

His alien overproduction has now collapsed. Electoral crashes seem only to preserve the once historic party’s shattered shell. Indeed, as long as PASOK participates in the Samaras government in order to prevent the country from sinking, it suffers disproportionate political costs. Its deterioration is rapid as the anti-rightist reflexes of its members are activated, accusing it of complete collusion with the New Democracy.

A large portion of its traditional electoral clientele is migrating towards the “indignant ideological and political mafia” represented by the kinetic Syriza. Venizelos will pay the price. PASOK, no matter how much it stood back to save the country from its precipitous plunge into the abyss, the voters despise it. It recorded the lowest percentage in its history, receiving 4.68% in the January 2015 national elections. It should not be forgotten that George Papandreou is also running in the same election with his own party called KIDESO.

In essence, he is splitting the remaining PASOK voters by attempting an informal revenge for his resignation, which he calls a “coup d’état”, bringing back unpleasant smells from the internal civil war of 2007. Papandreou finally suffers a humiliating electoral disapproval and is left out of parliament with a minuscule 2.46% of the vote. However, Venizelos’ days as party leader are now numbered as well. He stepped down as leader in June 2015, a little more than three years after being elevated to the post.

The baton to Fofi

It is the turn of Fofi Gennimata to take the baton of leadership of PASOK. On 14 June 2015, in an internal party election where only 52,000 friends and members take part, the daughter of the late George Gennimata wins the leadership from the first round with 51.6%. Co-candidates for the presidency at that stage are Andreas Loverdos and Odysseas Konstantinopoulos. Two years later, it is fully aware that it is venturing a grand coalition of forces under a new unified center-left body with the election of its president from the grassroots.

In November 2017, elections are held for the leadership of the Democratic Coalition. A total of nine candidates are participating, including Fofi Gennimata, Nikos Androulakis, Giorgos Kaminis, Stavros Theodorakis and Yannis Ragousis. Fofi wins the first round in which more than 210,000 voters turn out. She clearly prevails in the second round with 56.75% against Nikos Androulakis. Next spring, the party is officially renamed the Movement of Change, from which Stavros Theodorakis’ Potami, which will gradually disband, will leave in a few months. In the six years that she remains leader, Fofi has made a soulful attempt to tidy up and renew the party organizationally, as well as to bring it back to its identity choices.

Mostly she is trying to gain electoral viability. In a show of force, she expels her predecessor in the leadership, Evangelos Venizelos, from the party. Just as George Papandreou had previously expelled Kostas Simitis from the parliamentary group. The truth is that Fofi Gennimata will fight it bravely, as a consciously fighting lady of politics, until her death, at only 57 years old, in October 2021. But already since last autumn the discussion about the internal party elections has begun. She has announced that she will run again. Unfortunately, she didn’t make it.

Androulakis victory

On December 5, 2021, 270,000 voters go to the internal party polls. They queue up at polling stations to elect a new party leader from among six candidates – Nikos Androulakis, Andreas Loverdos, Pavlos Christidis, Pavlos Geroulanos, Haris Kastanidis and – surprise – the kindly emerged centrist George Papandreou. Who is running for president for the third time in 17 years. He has already rejoined the party after his misguided experiment with KIDESO to enter the succession race under the slogan “New Change”. Obviously, he was not a Hydraian hanging around Larissa, according to the line of the surrealist Nikos Engonopoulos in his poem “Bolivar”.

But at 69, he doesn’t exactly embody a liberating general who optimistically illuminates the party’s destiny. Nikos Androulakis finally prevails in the first round and is elected leader of the Movement in the second round, winning with an overwhelming 67.1% against George Papandreou. The new president initially creates expectations of electoral ascendancy after his election. Indeed, he is tweaking some higher percentages than in the past in the 2023 national elections. And as SYRIZA is a crisis after its electoral collapse and the departure of Alexis Tsipras, hopes for PASOK’s surge to second place are raised. They go for naught in the end and they are disproved in the 2024 European elections.

Inevitably, challenging the leader from within necessarily leads PASOK to elections for new leadership. In today’s first-round ballots, Nikos Androulakis (a third-time candidate), Pavlos Geroulanos (a second-time candidate) and Nadia Giannakopoulou, Anna Diamantopoulou, Haris Dukas and Michalis Katrinis are competing for the people’s choice. It is unknown who will be the two of them preferred by the voters to face each other in the second round on 13 October, which will declare the 7th in line to become the president of PASOK. The important thing is that the current PASOK does not have as its would-be leaders charismatic messiahs, gifted populists, timid visionaries and privileged heirs.

The whole of PASOK

Nuggets of these characteristics may be present in each candidate’s profile. Legitimate. But they don’t fully describe each one. Especially since the party does not attempt to imitate the cliché “the whole PASOK in a tiny package”. Marching into the third decade of the 21st century, it has probably exhausted the reserves of its old glorious dowry. It has disposed of the incense icons of the past. It has passed the nostalgic litanies of the mythical “oh, good times!”

In the current juncture, being a serious party probably requires as its president a personality who possesses fortitude, grit, stamina, experience, fortitude and awareness of high level politics. These are prerequisites for ensuring a forthcoming electoral political success. Let’s say the filling, without feverishness or artificial terminology, of the chaotic vacuum in the opposition that the vaporized Syriza cannot serve. So PASOK does not need as its leader a colourless figure who will provide it with ephemeral flashes. Either way, history has filled its landfills with political expendables and filled its cemeteries of memory with irreplaceables.

Ask me anything

Explore related questions