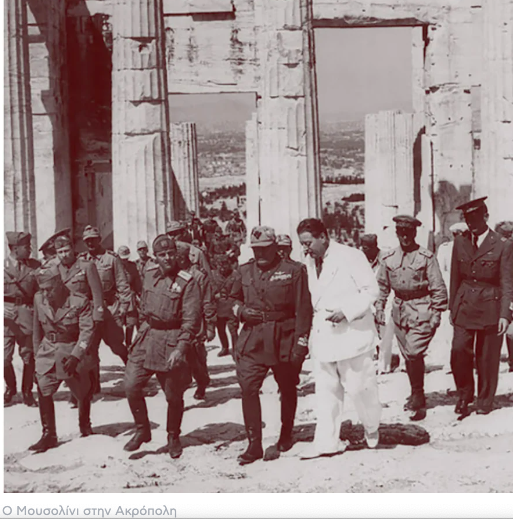

One of the lesser-known but significant issues from the WWII occupation of Greece is the forced occupation loan extracted by the Nazis and, to a lesser degree, the Italians. This controversial topic is thoroughly explored by journalist and political analyst Giorgos Harvalias in his book “Jawohl! Blood, Oblivion, and Subjugation,” with its 4th edition published in 2024 by Pedio Publications.

Nazi Strategy to Exploit Greece’s Wealth

Before WWII, Germany was Greece’s primary trade partner. However, when the invasion was decided, a detailed plan was drawn up not by military leaders but by executives from German companies, spearheaded by the industrial giant IG Farben. Historian Mark Mazower highlights that these businessmen, familiar with the Balkans, were sent to oversee the planned plunder of occupied countries, including Greece.

The Kiel Institute, which would later become renowned for its involvement in Greek debt matters, laid out a scheme targeting six key sectors of the Greek economy: food industry, shipbuilding, textiles, rubber production, iron manufacturing, and mineral mining. This plan was authored by Karl Schiller, a Nazi economist who would later become Finance Minister in post-war West Germany.

Systematic Pillaging of Greek Assets

Within days of Greece’s capitulation, senior executives from Krupp, Germany’s largest industrial conglomerate, arrived to seize Greece’s metal reserves. German representatives also took control of Greece’s electricity companies, shipyards, and other critical industries. Even Greek tobacco stocks vanished, and several Greek companies, such as the paint industry leader XROPEI, were confiscated by the Nazis.

The financial exploitation didn’t stop there. Deutsche Bank and Dresdner Bank linked up with Greek banks like the National Bank and the Bank of Athens, aiming to place the Greek financial system under full German control.

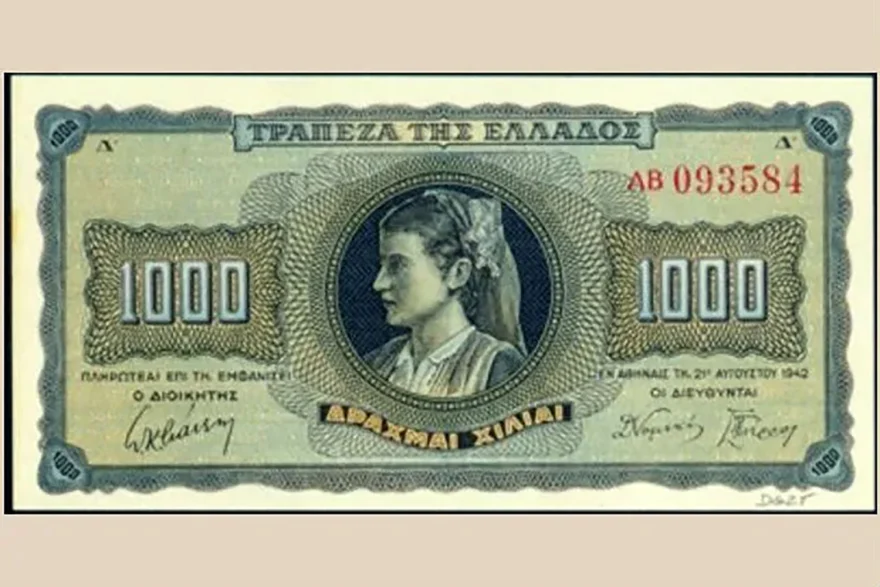

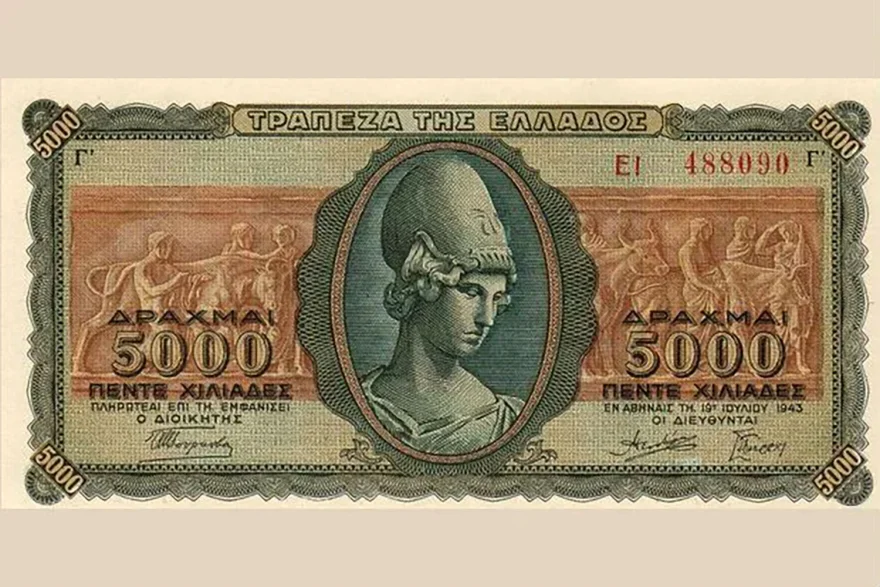

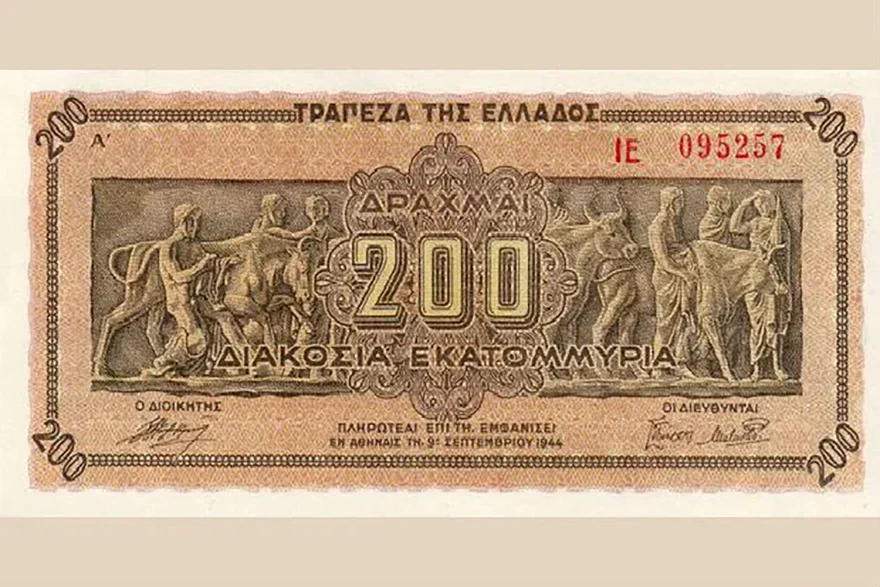

The “Occupation Marks” and Inflation

For several months, the Axis powers in Greece used “Reichskreditkassenscheine” (R.K.K.S.), better known as “occupation marks,” along with Italian “Mediterranean drachmas.” These worthless currencies enabled German and Italian troops to buy Greek goods without real payment, contributing to rampant inflation and skyrocketing prices in occupied Greece.

The Sbarounis Report and the Forced Loan

In 1942, to legitimize their looting, the Germans sought a formal agreement on occupation expenses. Greek economist Athanasios Sbarounis bravely countered their extortionate demands, arguing that the cost of maintaining excessive forces in Greece should not be borne by the Greek state. His report led to the creation of the “forced occupation loan,” a legally binding agreement that remains a cornerstone of Greece’s claim for repayment today.

The Rome Conference of 1942: Formalizing the Loan

In March 1942, a secret Italo-German agreement was signed in Rome, requiring Greece to pay 1.5 billion drachmas monthly for the Axis forces stationed there. Any additional expenses were treated as an “interest-free loan” to Germany and Italy, to be repaid at some undetermined future date. This agreement forms the basis of modern Greece’s demand for reparations.

By the summer of 1942, the Germans were draining Greece’s economy to fund their campaigns in North Africa, with monthly payments reaching astronomical sums. The loan’s burden pushed Greece’s GDP to the brink, surpassing even the costs of maintaining the occupation forces.

Ask me anything

Explore related questions