I didn’t know any of the things I learned from talking to him, except for one: that Professor of Physics Konstantinos Fountas is set to assume the presidency of the CERN Council on November 6. You may ask, what is this CERN? The answer is overwhelming. It’s the scientific institution based in Geneva, considered the best, the highest in the world. Its acronym stands for the European Organization for Nuclear Research. It was established in 1954, and Greece was one of the twelve founding members!

I also didn’t know that the physicist Theodoros Kougioumtzelis, known as the “Greek Oppenheimer,” played a key role. He also established “Demokritos,” and it was him who brought Greece into CERN. Moreover, CERN invented the Internet. I didn’t know either that most of the minds behind the creation of the atomic bomb came from Europe. Or that every secretary of the relevant ministry proposed that we leave CERN to avoid paying the annual 12 million euro participation fee! That in 2016, they were about to throw us out because we couldn’t pay! And that now, from being at the bottom rung, we’ve shot up to the top floor of CERN. Because, take note, on November 6, in addition to Mr. Fountas becoming president, we might also have Professor Paraskevas Sfikas as the executive director!

Scene 1

“My professor Giannis Diakogiannis”

DIMITRIS DANIKAS: Let’s say I’m someone who knows absolutely nothing, and I read one day that Konstantinos Fountas, professor and nuclear physicist, is taking over as president of some institution called CERN. Who is Fountas? Was he interested in such things from a young age?

KONSTANTINOS FOUNTAS: Yes, more or less. Essentially, I decided to pursue physics in high school—back when it was the Six-Year Gymnasium.

D.D.: Which Gymnasium did you attend?

K.F.: I started in Pylos, Messinia, where I was born, and completed the first two years there. Then I moved to Athens and went to the 14th Boys’ Gymnasium on Faliro Street.

D.D.: Did you have a good teacher?

K.F.: In Athens, I had an excellent teacher, and we would even go out together to little taverns and such. This was from 1973 to 1976. His name was Giannis Diakogiannis, and I’ve lost touch with him.

D.D.: So, there were important teachers in this poor country.

K.F.: Absolutely! And later on in the preparatory schools too. You know, back then, university entrance exams were tough. Only about 10% got in, if I remember correctly, and everyone attended the big prep schools in Athens. There, at “Gnomon,” I met Mr. Panagiotis Moustakas, with whom I’m still in touch today. He was the one who really taught me physics.

D.D.: So, there’s a solid foundation of significant teachers and professors.

K.F.: Always! For me, for example, apart from my mother, my elementary school teacher in Pylos was very important. I kept visiting her until she passed away in her 90s. A teacher in elementary school plays a huge role in shaping a child’s character.

D.D.: What did your father do?

K.F.: He was a grocer. Back then, grocery stores were even open on Sundays, so he didn’t have much time to influence my life.

D.D.: Do you have siblings?

K.F.: I have a brother; he’s a mathematician.

D.D.: So, the two children of a grocer excelled. That’s Greece for you, Mr. Fountas—the Greece we unfortunately keep hidden.

Scene 2

With a scholarship to Columbia

D.D.: So, from Athens to Ioannina?

K.F.: I then went to Ioannina as a student of physics and graduated in 1981.

D.D.: Still with good professors?

K.F.: Yes, there were good ones. People had started coming back from America. My father didn’t have the money to send me abroad, so my only hope was the scholarships offered by American universities.

D.D.: From the bad universities in the “bad” America… I’m being sarcastic.

K.F.: I had the best impressions.

D.D.: Of course, you did—why would you have bad ones?

K.F.: They wrote me letters of recommendation. There was Giannis Vergados, with whom I still have coffee, and the late Pericles Tsekeris, among others. They had gone to America, and because, you know, students start to imitate their professors, I decided I would go to America too. I applied and got a scholarship to Columbia University in New York. I went there and finished my Ph.D. in 1989.

D.D.: What was your dissertation on?

K.F.: It was on high energies.

D.D.: What does “high energies” mean?

K.F.: It means looking inside the proton. The higher the energy, the smaller the distances you can see. Today’s accelerators and labs work like microscopes. High energies let you look inside the proton, which contains quarks, gluons, and other particles.

D.D.: What exactly is a proton?

K.F.: A proton forms atomic nuclei. You consist of atoms. Atoms have nuclei, and electrons orbit around them. The nucleus is made of protons and neutrons.

Scene 3

Cheap electricity from nuclear reactors

D.D.: How do these things affect our lives?

K.F.: You can never predict what will come out of such research. For example, when Otto Hahn and Lise Meitner split the nucleus before the war, they didn’t do it to create reactors or atomic bombs. They did it purely for knowledge. Yet, reactors came out of it, which solved an energy problem. Right now, I can’t tell you that we’ll produce a washing machine from the Higgs particle, for instance.

D.D.: I’m not asking about washing machines—I’m talking about nuclear energy. We don’t have a reactor in Greece, right?

K.F.: “Demokritos” had one in the past, but not anymore.

D.D.: Isn’t it tragic that Greece doesn’t have a nuclear reactor?

K.F.: I haven’t studied the matter. Greece currently generates some of its energy from “green” sources, like solar power and hydroelectricity. To answer your question, I’d need to see its consumption, energy needs, and whether green energy will suffice in 50 years. But from what I see elsewhere, like Germany stopping its nuclear plants, that was a huge mistake.

D.D.: That’s what I say, because France still has nuclear plants.

K.F.: When I lived in France, the radiators in my home ran on electricity. I was terrified that I’d have huge bills, but the electricity was cheap because it came from nuclear reactors.

D.D.: Why don’t we do the same? Why not use nuclear reactors?

K.F.: I can’t say, but as I mentioned, you need to assess what Greece really needs. If you tell me that green energy can meet all of Greece’s demands, why bother with nuclear reactors?

Scene 4

“Quantum Physics was born in Europe”

D.D.: I see you were elected Associate Professor at Imperial College in the UK and worked on the Large Hadron Collider.

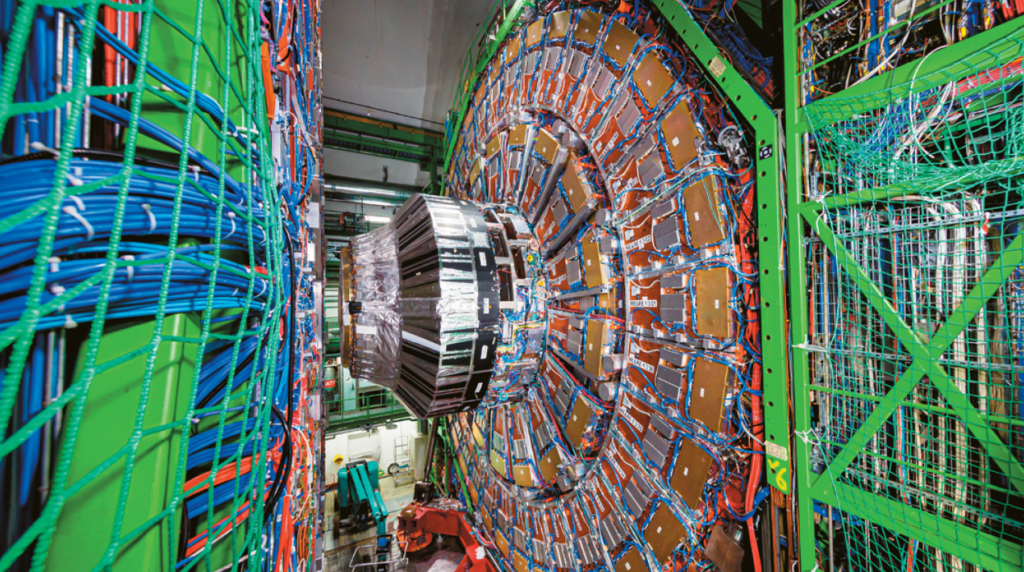

K.F.: Yes, the LHC is CERN’s accelerator.

D.D.: What exactly is the Large Hadron Collider?

K.F.: It’s a circular accelerator, a 27.5-km tunnel in Geneva, where beams of protons move. Imagine groups of protons, and each group has 10^11 protons. They collide 40 million times per second, recreating conditions like those that created the universe. This is how the Higgs particle was discovered.

D.D.: What is the Higgs particle?

K.F.: We have the so-called Standard Model in physics, which describes all particles. To explain nature, humans, and everything around you, you need 12 particles: 6 quarks and 6 leptons, plus their antiparticles and the way they interact. This whole model is called the Standard Model. High-energy physics started mainly after WWII.

D.D.: Did Oppenheimer or Einstein work on this?

K.F.: Of course! All of this is based on quantum theories. Einstein was one of the fathers of quantum physics.

Scene 5

“Most who made the atomic bomb were Europeans”

D.D.: Americans have the money, but Europeans have the brains.

K.F.: Before the two World Wars, Germany had what we now call the Max Planck Institute. Max Planck was one of the founders of quantum theory, a professor in Berlin. Back then, the institution was supported by the Kaiser and was not called “Max Planck,” but Kaiser-Wilhelm-Gesellschaft, meaning the Kaiser Wilhelm Society. The money was there, in Berlin, in Vienna. And, of course, the universities of England, such as Cambridge, Oxford, all of them, were the center of the world. With World War II, Europe was destroyed and stopped having money. Most people left, many fleeing from Hitler. Most of those who built the atomic bomb in Los Alamos were Europeans.

D.D.: So, the center of physics moved from Europe to America.

K.F.: After the War, and with encouragement from Oppenheimer, Europe created CERN. The reason CERN was founded was that no single country had the money to build its own center. Two people proposed the idea for CERN: Oppenheimer, who was then at Princeton, and Isidor Isaac Rabi, who was at Columbia. In fact, I had the honor of meeting him. Rabi was the elder statesman in the Physics Department at the time. I would go for a walk on a Sunday, for instance, and bump into Rabi and his wife.

Scene 6

Kouyoumzelis, “the Greek Oppenheimer”

D.D.: What is CERN, and what does its name mean?

K.F.: It means the European Council for Nuclear Research. It was founded in 1954, and Greece was one of its 12 members.

D.D.: How did that happen? Because of Queen Frederica? I’ve heard that Frederica had gone to Los Alamos.

K.F.: From what I’ve been told, she attended a lecture by Heisenberg in Greece and was thrilled. And, as far as I know, she played a key role in the founding of Demokritos.

D.D.: So, Frederica supported Demokritos?

K.F.: Yes, that’s what I know. A key role was played by a physicist named Theodoros Kouyoumzelis. There’s even a book about him—though I haven’t read it—titled The Greek Oppenheimer. He created Demokritos and, as I’ve heard, he was the one who got Greece into CERN. In fact, he was the vice president of CERN from 1972 to 1975. Now, I am vice president from 2022, and in January, I will be president.

Scene 7

“They said we should leave, stop paying 12 million a year”

D.D.: Isn’t it incredible that there’s such exceptional human capital, yet at the same time, there’s no infrastructure in Greece? How do you explain that?

K.F.: The talent alone isn’t enough. What’s needed—and what we lack, what we don’t have compared to larger countries—is continuity. Here, someone might come along who’s brilliant, does something great, but the system lacks continuity and organization. Let me give you an example: The Hellenic Foundation for Research & Innovation (ELIDEK) was created by Mr. Fotakis, who was then the Deputy Minister for Research and Innovation in Tsipras’s government. This foundation gave scholarships to students and professors for laboratories. Then Fotakis left, and they were saying they’d abolish it. Fortunately, they didn’t, and kudos to them! And recently, they’ve started strengthening it, which is very good.

D.D.: If you were to meet the prime minister, what would you tell him to help Greece stand tall and come closer to European countries?

K.F.: Strengthen basic research in Greece, strengthen meritocracy. And at the same time, adapt the education programs to the country’s economy—I think they’re either doing or want to do that. Let me give you an example: at Imperial College, in the fourth year, we had a course worth 10% of our degree that taught us how to start a startup company. So, a physicist graduating from Imperial, if they didn’t want to pursue an academic career—and only a small percentage does—had the knowledge to start a company that could produce something beneficial for the country. We don’t have anything like that here in Greece.

Scene 8

“In 2016, they were going to kick us out because we hadn’t paid”

D.D.: How much money does Greece give annually?

K.F.: Greece gives about 12 million euros to CERN. We pay one-hundredth of CERN’s budget—its budget is 1.2 billion, and we pay 1%. It’s based on GDP. At the same time, we contribute around 600,000 to the experiments we participate in, and we also have old debt. In 2016, they were going to kick us out because we hadn’t paid. We pay 2.5 million a year towards that debt—that was my first job when I became Greece’s representative in ’16, to negotiate the debt. They agreed to have it repaid by 2035, and currently, we pay 2.5 million a year. At one point, we owed 30 million euros. CERN’s charter says if you haven’t paid for two years, you’re out. Right now, we have 200 people doing research at CERN. But they’re not all there. Someone might be at the University of Ioannina but connected to CERN—they’re the so-called “users.” Inside CERN, there are about 100 Greeks. To give you some numbers, we currently have around 60 postdocs.

D.D.: What’s that?

K.F.: It’s the fellowship you get after your PhD. The typical career path of a researcher, after finishing their PhD, is to do two or three postdocs, each lasting two years, and then apply to become a professor. So, there are 60 Greeks. There are about 10–15 doing their PhDs. Then there are others, and possibly more, who are doing their master’s in computing. Not all of them are physicists, though; some are engineers or from other fields. Only a small percentage are doing pure physics. Even in CERN’s finance department, there are Greeks. We also have many permanent staff. While Greece pays 1%, it has 2.5% of the permanent workforce.

D.D.: What do we stand to gain from this participation?

K.F.: There’s a lot to gain. Where we have a problem is with what’s called “industrial returns.” CERN tries to return some of the money it receives to countries in the form of contracts with companies. For example, if CERN needs a hundred shielded iron doors for the accelerator, it gives the contract to a Greek company, so some of the money we pay comes back in contracts. We were doing well in this until 2019. It has declined since, and we’re trying to fix it. Until 2019, Greece essentially got back as much as it was paying to CERN, whether in salaries for people working there or contracts or other means.

Scene 9

“The internet was created at CERN”

D.D.: What can CERN offer to the daily life of an ordinary person? In energy? How can we benefit?

K.F.: I don’t know if you know, but the internet was created at CERN. CERN is like a large city. When someone needed a paper from a certain building, they had to walk 4 kilometers to get it. So, a system was needed to transmit information without someone having to walk. And that’s how the first browsers were created. And because CERN’s charter forbids it from selling its research, it gave it away. If CERN had sold the internet, it wouldn’t need government funding today.

D.D.: Can we say that CERN is Europe’s Los Alamos?

K.F.: CERN doesn’t conduct military research. There’s another lab that’s its equivalent in America, Fermilab in Chicago. Essentially, CERN is Europe’s high-energy physics lab, and Fermilab is America’s. But CERN is superior. Remember how we said that the center of physics shifted to America? CERN allowed it to return to Europe. Imagine, even Americans visit us because they don’t have a lab with such energy capacity.

D.D.: There’s a race to get ahead.

K.F.: Exactly, it’s the West versus China. CERN has American support, without which nothing would happen. Unfortunately, we expelled the Russians—a mistake in my opinion, but it’s done.

D.D.: A political decision.

K.F.: Yes, it’s a political decision, not my concern.

Scene 10

The Greeks at the top

D.D.: How many people are at CERN?

K.F.: On a normal day, about 7,000 people. Not all of them work for CERN. Don’t forget it has many restaurants, hotels, and other services. It’s a whole city. The employees are about 2,500–3,000.

D.D.: Suddenly, in this massive scientific and research city, which competes with the Chinese, the boss is a Greek! Incredible!

K.F.: I am the president of the Council. The Council is the boss, consisting of representatives from the 24 countries that are full members. It determines the policy and programs of CERN, deciding on everything. The executive power is held by the director-general, who implements the Council’s decisions.

D.D.: What exactly does the president do?

K.F.: The president oversees the meetings of the Council, determines the topics to be discussed, and checks whether the Council’s decisions have indeed been implemented. They participate in all committees, such as scientific, political, and economic. But one of the most important things is that we try to ensure that when we make decisions, all countries agree, meaning we avoid having a minority and majority.

D.D.: Did you go as vice president during the SYRIZA government?

K.F.: No, Mr. Fotakis appointed me as Greece’s representative. I became vice president in 2022, when the Mitsotakis government nominated me. I can’t become it on my own; my country has to propose me. And now that I have become president, I was nominated by the Minister of Foreign Affairs, Mr. Gerapetritis.

D.D.: And how long will you remain president?

K.F.: Three years. Let’s also say that Greece has a very good reputation at CERN right now. At this moment, there is a Greek, a very distinguished person, a candidate for director-general. Mr. Paraskevas Sfikas from Athens. He is a professor at the National and Kapodistrian University of Athens and came to EKPA from MIT. He is one of the three candidates for the election of the director-general that will take place on November 6.

Conclusion

Greece from rock bottom to the top

D.D.: Imagine now, on November 6, we have Mr. Founda as president and Mr. Sfikas as director-general. CERN will become Greek!

K.F.: And think that in 2016 we were at the bottom there.

D.D.: And now we will be at the top. This is Greece, from the bottom to the top.

K.F.: And I hope it continues. And to answer your previous question, how I feel as president, I will tell you this: there are two major issues at CERN right now. We are upgrading the accelerator. And at the same time, there are experiments for a new program that will start in 2030. The cost for the accelerator is around 1 billion and then there are another 600 million for the experiments. This program must succeed—for research purposes, obviously, but it is also important because in this way we prove that we can carry out projects within the time frame we have set and within budget. Because the next project, the FCC, in which we are competing with the Chinese, will be a huge accelerator. It has a 90 km circumference, 10 times more energy, and costs 15 billion. So these two are the challenges for the president at the moment. First, to make the existing program succeed, and second, to lay the foundations for the next one. So that Europe can maintain its primacy and compete with the corresponding Chinese laboratory.

D.D.: With a Greek president, this is significant. And with a Greek director-general as well. Mr. Founda, I wish you all the best!

Ask me anything

Explore related questions