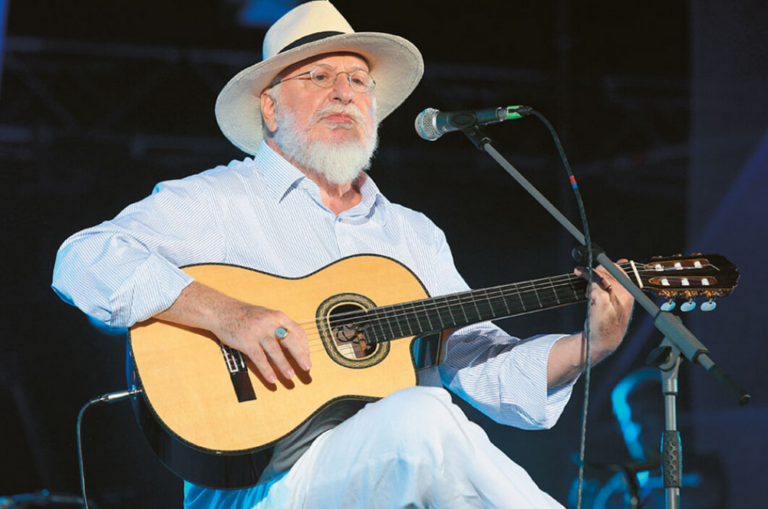

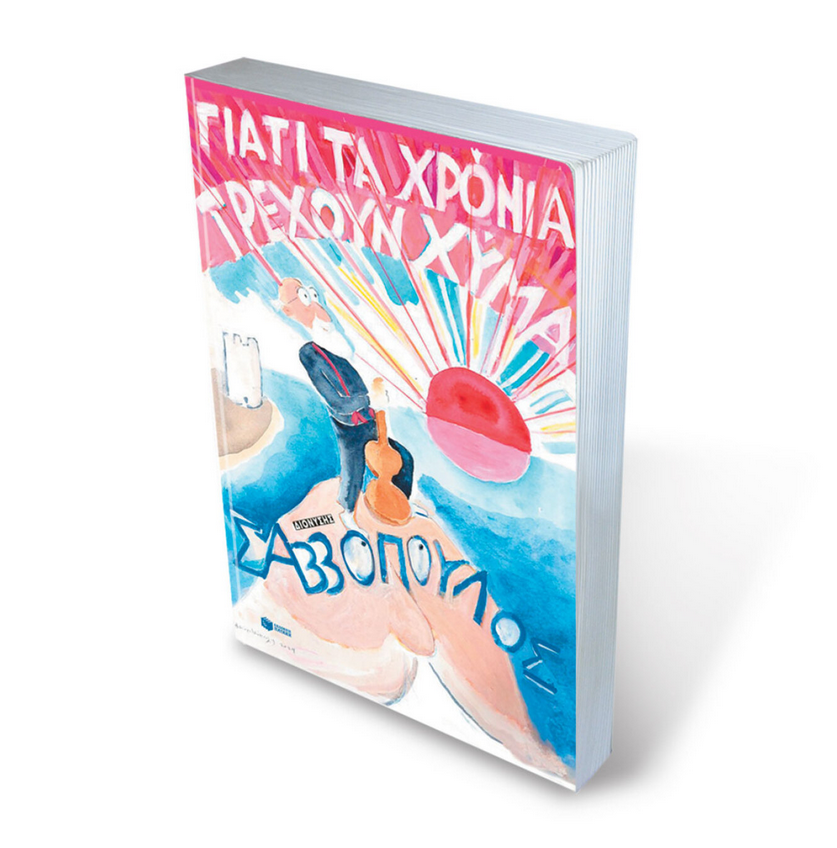

Deeply confessional, more than ever at 80 years old, exercising harsh self-criticism for his passions and mistakes in both his professional and personal life, and revealing the true face behind the role he created for himself, is Dionysis Savvopoulos in his autobiography titled “Because the Years Run Wild,” which has just been released by Patakis Publishers. And it is this unexpected, raw, and brave honesty of his, as well as his witty and enjoyable writing style – storytelling has, after all, been one of his strongest tools throughout time – that captivates, sweeps along, and even surprises the reader.

Because Savvopoulos was always perched on a pedestal, untouchable and full of contradictions that raised legitimate questions: familiar yet at the same time distant, dynamically present but elusive, polite yet eccentric, an excellent conversationalist but also dogmatic in his opinions from time to time. The fact, then, that he consciously chose to step down from this pedestal, to remove the armor of his myth, and expose himself publicly proves not only his courage but also his deep desire to ask for the account of his life and settle it.

The apologies

His “debts” are many and to many, as he himself admits. First of all, to his children, his two sons, to whom he was not always a good father, as he confesses deeply regretting.

“I slapped my children when they were little. Yes, sometimes I slapped them. I wish the earth would open up and swallow me now that I’m saying this. I am ashamed. I’m ashamed that you’ll all read this now. ‘Artist,’ they say, ‘a person with sensitivities’… I used to scold them too, screaming like a harpy. My little birds would look at me terrified…”.

When years later he apologized to one of his sons for the times he hit or insulted him, the son gave him the most sincere, completely justified, but also harsh answer: “Yes, but I don’t know if I can.” And when he later brought the matter up at a family table, he did not get the answers he had hoped for, the ones he needed to hear to calm his guilt. He admits it frankly in the book: “I really want this forgiveness, but I still don’t know how to ask for it.”

In his deep confession, he could not fail to mention the woman of his life, Aspa, with whom he has walked side by side for decades, through both the easy and the difficult times. Yet, even this ideal relationship in the eyes of the world, he does not idealize. On the contrary. He admits that there were times when they almost separated, that the conditions of his work and the temptations occasionally distanced him from her, and that they even lived apart for several months. However, the way in which he recognizes his mistakes and his choice to put himself in his wife’s shoes, to feel her, understand her, and ultimately justify her, is a sign of intelligence, bravery, and deep love.

“Sometimes we almost (separated), but we fell back into each other’s arms. And other times, there were days when the gravestone of everyday life would fall heavily upon us again. I worked in clubs full of young women, sexually willing and moreover in love with the protagonist. I felt like a little child who is put in a room where toy trains run, talking robots, a bunch of luxurious toys, but I wasn’t supposed to touch anything, just watch. ‘You wanted marriage, well here it is!’ I would blame her, the fool that I was. But even if I was tempted and sometimes went overboard, I confessed it to her. I couldn’t keep secrets from my wife. They suffocate me. What could I do? I tell her everything. After all, I’m a man, didn’t I have any excuse? No, I had no excuse. I could hear it in her cold silence. I could see it in her cold green eyes. I was a patriarchal type who was tortured by his very patriarchy. That’s how I was back then…”

But these are not the only apologies we find in his book. “Nionios” condemns himself for several other times he wronged or mistreated people, as he meaningfully emphasizes that even musicians are “little men, complex, insecure, with wounded egos, sometimes envious and intolerant, who when we start to play something or sing, we balance, we improve, as if we become more beautiful.”

His apologies are directed, among others, to Thanos Mikroutsikos – “What kind of stinginess was this on my part?” he wonders, referring to his failure to respond to Mikroutsikos’ repeated attempts to mend their cold, unjustifiably strained relationship – to Giorgos Dalaras for their quarrel at the big concert in ’83 at the Olympic Stadium – “because of my stupidity,” he admits without hesitation – but also to his close friend and the voice of “Acharnes” Nikos Papazoglou – “I lost the opportunity, the idiot, back then in Crete to hug him again.” And he never saw him again after that.

The Parties and the Demolition

The name and songs of Dionysis Savvopoulos have always been associated with a political tone. For many years, they were firmly linked to the struggles and messages of the Left, with which he himself aligned in his youth. “We gave our best years to the Left. Not in vain. We were teenagers, and it was these very years that opened the way to our hearts and illuminated, even if by accident, the sacred element of the society we share. It was these years and not their politics,” he clarifies in his autobiography, then explaining the reasons that led him away from this political direction and gradually to the opposite shore, always following his musical path.

“With ‘Kourema’ I made a shift to the Right, exhausted by the pseudo-progressivism of the time and its arrogance. It was a progressivism that was cloudy, counterproductive, very cultured, and completely anti-spiritual. Unfortunately, the Left allowed itself to be swept away by that cheap progressivism. Former Leftists who, justifiably, hated the Right because it once humiliated them and forced them to sign declarations of repentance, but also never got rid of their unspoken anger towards their own Left, which trapped them back then, once PASOK emerged, they all moved there. PASOK became the refuge for every wounded ego. Not to mention its populism. It was so irresistible that it negatively influenced the entire political system, almost all the parties. So much fanaticism,” he describes meaningfully.

He may regret many things, but for the song “Koloellines,” which became the flag of the most controversial album in his musical career, he doesn’t regret: “The kolohellenism, which is the heavy legacy of all of us, we mostly keep under control. But when it erupts collectively, you don’t know where to hide. It no longer matters whether we are right-wing or left-wing, and we become a mob of envious people, hungry for power.”

The Advice

Savvopoulos paid dearly, it’s true, for this song and the 1989 album it was part of. His large, fanatic audience, all those who had idolized him just a few years earlier for “Trapezaki Exo,” turned angrily against him. “My rift with the audience in ’88-’89 with ‘Kourema’ at the ‘Zoom’ in Plaka was the hardest of my life, but I endured it. I have it almost like a badge of honor… The public had now become cold with me, I had the human-repeller. I ended up playing in the empty ‘Zoom’ with about twenty clients, who moreover couldn’t stand me, they were heckling me, getting up and leaving… They threw coins at me on stage, shouting ‘shame,’ and leaving the room. Angry drivers surrounded me at traffic lights and cursed me with fierce eyes, passersby shouted at me from the opposite sidewalk. Others wrote insults on the wall of our house, calling me a traitor, saying I sold out…” he recounts the darkest side of his personal journey.

As for SYRIZA? He limits himself to the general but utterly dismissive statement: “I only think about all this fascinating story of the renewing Left, how it started and how it slowly ended up being this,” while vividly describing his reaction when he heard about the bank closures, just before entering surgery for a bypass, when he shouted from the stretcher to his family: “Lift it up! I have it in Eurobank.”

Now, having traveled most of his personal journey, sometimes with a “Truck” and other times with “Planes and Ships,” he is ready to pass the baton to the next generations, along with a piece of advice: “You, younger children of this state, who with its sacred madness and passion gave birth to Democracy, protect it. Protect the Democracy of our small country. May our land live, may our Democracy live.”

Ask me anything

Explore related questions