It’s a weekday afternoon. Guests at home sip coffee and chat before getting to the main event—the Tupperware party. A young woman presents the latest plastic containers to the gathered housewives, who, out of politeness or obligation, make a purchase. This scene, straight out of 1980s and 1990s Greece, now belongs to the past—just like the industrial Greece it once represented, with its factories that defined an era.

One such factory was the Tupperware plant in Thebes. Established in 1967, it was one of the four European facilities of the American plastic container giant and among the most advanced in the world. But times change, and plastic doesn’t sell like it used to. The parent company in the U.S. came close to bankruptcy, and as part of its restructuring, the Greek factory—once synonymous with airtight container demonstrations—officially shut its doors.

The Decline of “Made in Greece” Industries

It’s not just Tupperware. A series of closures of historic factories that once defined “Made in Greece” have turned into symbols of a fading industrial past. From Tupperware to Youla (which produced caps for sodas and beer), Pitsos, Frigoglass, Reckitt Benckiser (where Quanto fabric softener was made), Pirelli, Goodyear, TEOKAR, Keranis, Klonatex, the International Clothing Industry, the Madison sock factory, and many more—all have shut down, marking the end of an era.

When the Smokestacks Went Dark

Ironically, the 1980s and 1990s—often remembered as Greece’s most productive decades—were also when its industrial smokestacks began shutting down en masse. This period marked the country’s deindustrialization, which culminated in the decade-long financial crisis that began in 2008.

Sometimes, numbers paint a clearer picture than words. According to an older PwC report, 26,570 manufacturing businesses closed in those two decades, leading to the loss of 160,000 jobs. The question is: why did this happen in a Greece that once produced everything—from toothpicks to cars?

The answer is complex. On one hand, government and EU policies were often unfavorable or ill-fated for Greek industries. On the other, a mix of unfortunate events played a role. A fire, for example, led to the closure of Greece’s largest toy manufacturer, El Greco, in Ano Glyfada. Employees mourned their fate, saying, “Fotinoulis burned us,” referring to the electrical short circuit that ignited the fire—ironically in the production line of the popular doll of the same name, which was also a hit in Italy.

This decline began long ago, with major industrial giants like Piraiki Patraiki and the Skaramangas Shipyards collapsing. It continued over the decades, leading to the latest round of closures, such as the historic glass manufacturer Youla. Some of these shutdowns left deep marks, signaling the definitive end of an era.

“The Glass Shattered” at Youla

If this year’s closure of Tupperware represents the final nail in the coffin of a bygone era, last year’s shutdown of Youla was the shattering of glass—both figuratively and literally. As Greece’s last glass manufacturer and the largest in Southeast Europe, Youla closed its doors after 77 years of history. Acquired by the Portuguese group BA Vidro in 2016, the factory ceased operations, marking yet another chapter in Greece’s industrial decline.

Youla: A Glass Giant That Shattered

For Generation Z and older generations alike, Youla—named after the sister of its founders, Kyriakos and Giannis Voulgarakis—was the ultimate success story of the 1980s and 1990s. Nearly every Greek household had at least one of its glass products, whether a dish, an ashtray, or a decorative piece. But beyond its local presence, Youla became a powerhouse, exporting to over 80 countries and acquiring factories across the Balkans.

However, the high cost of energy and borrowing made the glass industry fragile in the face of global competition. In March 2024, the historic Youla factory in Aigaleo switched off its machines for the last time.

The Fridges Went Cold

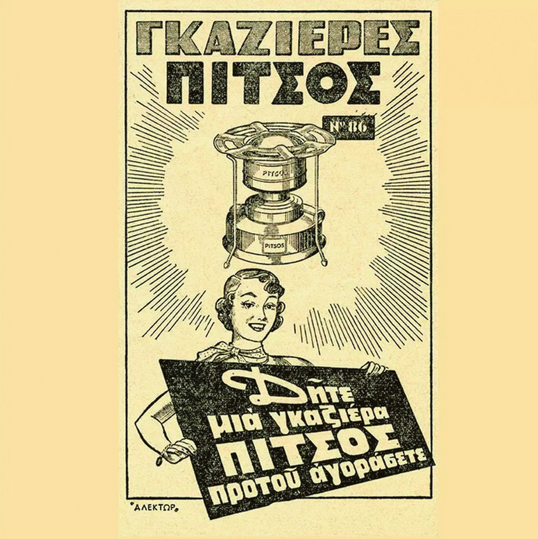

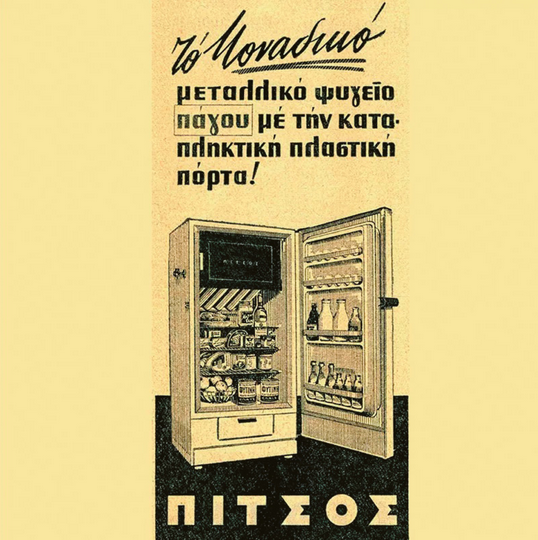

Though Pitsos was founded in 1865 by the Pitsos family, its first factory—producing gas stoves—opened in 1940. The real breakthrough came in 1959 when the company began manufacturing electric refrigerators, a move that cemented its place in Greek history. Pitsos became a household name, known for innovation and reliability, finding its way into nearly every Greek home.

Pitsos: The Pioneer of Household Appliances in Greece

Pitsos introduced groundbreaking innovations to the Greek market, such as No Frost refrigerators, the iconic POP stoves (with buttons that popped out at a touch), pyrolytic ovens, Astro fridge-freezers, and built-in home appliances. It also brought televisions with remote controls, heaters, vacuum cleaners, dishwashers, and many more products into Greek homes, becoming synonymous with modernity and innovation.

Over the years, Pitsos collaborated with German companies, like Siemens, and expanded significantly. However, in 2021, the German company Bosch Siemens Hausgeräte (BSH), now the owner of Pitsos, decided to close the historic and massive (53,000 square meters) factory in Rendi. The plant, which had produced stove tops for the international market and other home appliances, was shut down despite the employees’ efforts to keep it open.

While the factory has been repurposed and is now in the hands of Sklavenitis, the Pitsos legacy wasn’t completely erased. The brand was revived by another Greek company, Pyramis, breathing new life into a name that had been a household staple for decades.

The Strike That “Burst” Pirelli

“The tires on my car are Greek,” was a popular sticker on countless cars, trucks, and buses in Greece. Most of these vehicles were fitted with tires from the Italian tire manufacturer Pirelli’s factory in Patras, which boasted the most modern equipment.

However, a major strike in the factory played a pivotal role in its downfall. The factory, once a symbol of industrial success in Greece, struggled with the impact of labor unrest, contributing to its eventual closure. Despite being an important player in the Greek tire industry, Pirelli’s factory in Patras couldn’t withstand the challenges posed by labor strikes and the evolving economic landscape.

In 1991, the Pirelli factory in Patras unexpectedly closed and moved to Kozanli, Turkey, where labor costs were significantly lower. Several theories exist as to why the Italian company decided to shut down its Greek operation, with the most widely accepted version suggesting that after prolonged labor strikes, workers were finally ready to accept a 5.5% wage increase offered by the management. However, after the intervention of unionists from Athens, the strike continued, demanding a 6% increase. The Italian company responded by closing the factory.

Another theory suggests the factory was closed in retaliation after the Greek government stopped making direct tire purchases for the Athens Urban Transport Organization (EAS) and instead held a tender, which a South Korean company won. According to this scenario, Pirelli had prepared tire stock for the 1,800 buses of the EAS, but with the tender results, they faced unsold inventory and the loss of guaranteed government contracts, prompting them to relocate to Turkey.

The End of Nissan-TEOKAR

In the winter of 1962, car parts importer Nikos Theoharakis agreed to import cars from a then-unknown Japanese manufacturer in Europe. That same year, a Nissan Pickup 320 arrived in Greece. It was the first vehicle from what would later become an automotive giant to roll onto European soil. This marked the beginning of Nissan’s journey in Europe, with the company eventually forming a significant part of Greece’s industrial landscape under the TEOKAR factory. However, much like other industrial giants, TEOKAR eventually faced challenges and closures as part of the broader decline of Greece’s manufacturing sector.

The partnership between Nikos Theoharakis and the Japanese car manufacturer Nissan grew so strong that Theoharakis convinced the Japanese to approve the transfer of technology to Greece. He was granted permission to open the first of Nissan’s 48 factories outside Japan, which was not a direct subsidiary of the Japanese company.

Thus, in January 1979, with the presence of Nikos Theoharakis, a Nissan representative, and officials, a worker from TEOKAR laid the foundation stone for the factory, covering an area of 35,000 square meters, where “Greek” cars would be produced. Among the first cars produced were the iconic Datsun Pickup 1500, Datsun Cherry (in 1.0 and 1.2-liter versions), Nissan Sunny, and the 100NX in 1991. In the first year of operation, 4,685 cars were assembled. The Greek state also played a role, starting in 1981, by allowing the sale of cars assembled in Greece with partial credit, in contrast to imported vehicles.

However, while Nissan planned to build a larger factory in Volos to cover all of Europe, the Greek government, which insisted on having a majority stake in the investment, began undermining it through various decisions. Among these was the sudden announcement of the scrappage scheme, which disrupted the production plans, and the unexpected cessation of the program, leaving the factory with unsold stock. Additionally, changes to excise duties (E.F.K.) further complicated matters.

When Nissan President Yutaka Kume visited Volos to discuss new investment opportunities, no Greek officials were willing to meet with him. He was invited to London, where he met with Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher, and the inevitable happened. TEOKAR ceased car production in April 1995, while Nissan’s new factory in Sunderland was already operational.

Quanto Fabric Softener and Its Greek Connection

Quanto, the fabric softener produced at Reckitt Benckiser’s factory in Chalkida, became one of the British multinational’s hero products. Known for its iconic “Greek islands” scent, Quanto gained popularity both locally and internationally, becoming a staple in many households. Its production in Greece was part of the wider industrial landscape that saw global brands leveraging Greek factories to meet regional demand.

For more than two decades, Greece produced perhaps the most popular product of the British conglomerate Reckitt Benckiser, as well as the laundry detergent Finish Salt. The factory ceased production at the end of 2022, and the management sold the 9,328 square meter property in the first two months of 2023. This marked the end of an era for the local industrial scene, as another iconic production facility was closed.

Ask me anything

Explore related questions