Naked youths, sometimes wrestling like modern boxers and other times wandering while holding strings of fish; imposing bare-chested noblewomen with elaborate skirts and refined dragonfly-adorned jewelry; blue monkeys (!) climbing rocks where crocuses grow; ships decorated with flowers, swallows, and various nature symbols lined up, ready to sail and conquer the seas—these are just some of the elements observed in the famous frescoes of Akrotiri in Santorini, revealing many aspects of that unparalleled civilization that showed astonishing signs of development even in prehistoric times.

If it weren’t for the earthquake that, in the 17th century BC, covered the houses, belongings, and all the goods of the Thera inhabitants with lava—forcing them to abandon the settlement of Akrotiri to save themselves—we likely wouldn’t have gained such valuable insights into one of the most advanced civilizations of the Bronze Age.

One only needs to visit the region, which is currently facing challenges, to grasp the great wonder of Akrotiri, a site that appears to have been first inhabited in the Late Neolithic Period—around 4500 BC—and thrived during the Late Cycladic Period until it was completely buried beneath lava during the so-called Minoan eruption.

Trade and Customs

Can you imagine them strolling around, joking or flirting as they prepared for their daily activities, playing the lyre and drinking their wine—already famous even then—or weaving some of the luxurious fabrics they traded in distant lands?

In this bay, which once provided a safe harbor for ships—long before Kalliste (Santorini) took on its crescent shape after the volcanic eruption, inspiring Plato’s imagination to associate it with the lost Atlantis—one of the Mediterranean’s greatest civilizations flourished.

Situated directly across from the equally advanced Minoan Crete and the grandeur of Knossos, to which the prehistoric community of Thera was closely connected, the island and its inhabitants developed their own high-level culture.

The alignment of trade routes and cultural influences was never random for these prehistoric inhabitants, just as it wasn’t for the ancient civilizations that later ensured mutual influence in their customs and rituals. The close relationship between Egypt and the prehistoric civilization of Thera is evident not only in the symbols used in frescoes, rosettes, and everyday or religious practices.

However, unlike Knossos and Egypt, where a powerful king stood at the center of society from an early stage, Santorini shows no evidence of imperial dominance. Instead, an elite class prevailed—distinguished by its intelligence and capabilities. Displays of power were just as important here as in Minoan Crete, where similar deities appeared—an early depiction of Poseidon, symbolizing earthquakes under the name Enosichthon (meaning “Earth-shaker”), was dominant in various artistic representations.

The symbols initially used on the vessels and later in the famous frescoes reveal much about how society functioned on the island: for example, the long garments of the passengers aboard the ships in the beautiful fresco of the ship procession indicate a high social status and demonstrate the distinguished community that left its mark. This is also evidenced by the expensive fabrics found intact, buried by the residents in hopes of retrieving them upon their return, as early signs of the catastrophic eruption were already evident.

“The inhabitants must have perceived the warning signs and left the island before the disaster, as no human skeletons were found in the houses and streets discovered by archaeologists in the 20th century,” writes Roderick Beaton in his fascinating book The Greeks (Patakis Publications), highlighting, of course, that “farther from the island, despite how terrifying the events might have been at the time, the eruption of the Thera volcano caused less disruption over time than might have been expected.”

The Minoans appear to have calmly dealt with the event, as they had experienced previous disasters. However, the consequences of this event may have worked in a latent way and may not have manifested immediately,” argues the well-known academic, aligning with the latest theories that reject the notion that the Minoan civilization was destroyed by the eruption of the Santorini volcano.

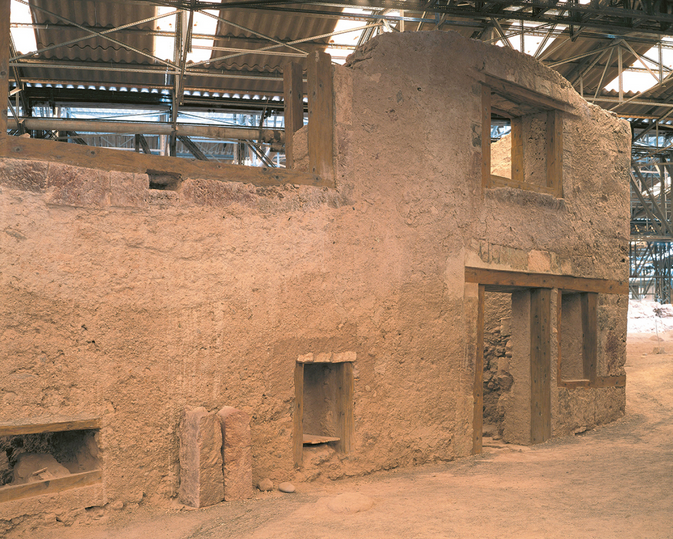

Nevertheless, signs of the urgent situation that forced the population to flee, analogous to Pompeii, are found in the fact that the inhabitants of Akrotiri hid various items—apart from fabrics—materials in niches within the rooms, indicating their belief that they would return to their homes. These impressive buildings with multiple floors and hewn stones, which Spyridon Marinatos called Xestes (known as such to this day), are unique in the Mediterranean world.

Protection System

It is remarkable that the prehistoric Thera inhabitants, already familiar with earthquakes, had developed an early seismic protection system, reinforcing their buildings with slate slabs or pebbles placed on compacted soil.

They built roofs with wood and reeds, placing compacted soil on top, which acted as insulation, ensuring coolness in summer and warmth in winter. The ground-floor rooms were presumably used as workshops or workspaces, while the upper floors were the main rooms, as evidenced by the beautiful frescoes that adorned them.

This highly developed civilization impresses not only with the wealth and technology it developed but also with its cosmopolitanism: their ships sailed across the Mediterranean, reaching the farthest corners of Asia Minor, where rivers depicted on the vessels flowed. Gold was abundant, and the adornment of women was rich, just as the garments referenced similar customs not only in Minoan Crete but also in Egypt.

Through her fascinating studies, like the one on Akrotiri titled Akrotiri-Santorini (Militos Publications), Nanno Marinatos, the daughter of archaeologist Marinatos, reveals many details about the close relationship between the Akrotiri civilization, Crete, and Egypt, comparing rituals as revealed in the corresponding details. She explains, for example, the presence of monkeys (!) in the frescoes from the Xestes: she reminds us that the Egyptians wore monkey amulets as talismans and occasionally associated them with the fertility god Bes. It is no coincidence that these monkeys were always near goddesses, as seen not only in the frescoes but also in the sealing cylinders of the Near East.

It is astonishing to see monkeys holding swords (!), jumping on mountains, or playing instruments. All these, according to the well-known scholar of Minoan Civilization, constitute evidence of the life cycles that this ancient civilization honored in its own way.

What Came to Light

It was enough for an olive branch found in the Caldera of Kameni in Santorini to pinpoint the volcanic eruption with relative accuracy, revising the initial estimate back to around 1613 BC, rather than 1450 BC, as was previously thought. Even earlier, Nanno Marinatos had placed it in a different chronological framework, using findings and vessels as her basis.

It was the largest eruption experienced by humanity in the last 10,000 years, and one of the reasons most archaeologists, such as the Englishman Arthur Evans and Spyridon Marinatos—who carried out excavations in Akrotiri and tragically died in the same area due to an accident in 1974—believe that the Minoan Civilization was destroyed. However, a series of findings and comparisons, as well as geological studies, like that of Paraskevi Nomikou conducted in recent years, have overturned these claims, suggesting that other external factors, not the volcano, caused the gradual collapse.

And we can all imagine the scene after the famous eruption: “In 1500 BC, only mounds of white ash are visible, marked by black pyroclastic flows, which at the moment of the eruption must have reached temperatures of several hundred degrees. No living organism could have survived the destruction. Even after half a century, the vegetation that would have begun to sprout would have been stunted. The sea winds scour the land, creating dangerous and changing ravines, scattering ash and gravel far into the sea. A long time will pass before any daring sailor sets foot on Thira again,” writes Beaton in his book The Greeks.

How the Settlement Was Found

It all began with the need to construct the Suez Canal (!) in the second half of the 19th century, when French engineers turned to Thira to procure the valuable pumice for insulating the canal’s walls. The indications of a civilization buried beneath the earth led French archaeologists to Santorini in 1870, who conducted research in the area with the help of specialist geologists.

The first excavation took place at the location of Favatás, which was named so because it produced a lot of fava beans, which had long been one of Santorini’s main and renowned products. This was south of the present-day Akrotiri, where the first archaeological remains were uncovered.

Excavations continued under Marinatos, after a local resident pointed out a valuable spot: the goal of the then Curator of Antiquities for Crete was to prove the direct relationship between the Minoan and the Thiraic civilization—and importantly, unlike Evans, he did not make questionable and later interventions in the settlement. What came to light from Marinatos’ work, and continued with the excavations carried out by Christos Doumas, was an incredible city with dense construction, multi-story buildings that had never been uncovered before, with beautiful frescoes, specially designed rooms, storage spaces, and workshops.

There were, of course, also the sanctuaries where rituals were performed, but the spaces were very well connected with paved roads. The highly developed drainage system and the well-organized urban planning are impressive. The fact that many of the works for the road extensions were left unfinished also suggests the abandonment of the inhabitants, presumably after warnings of an impending eruption.

However, the lack of fortifications in both Akrotiri and Knossos indicates that it was a peaceful community in great prosperity, unlike the later Classical period when Thira became the only island that refused to join the Delian League, fighting alongside Sparta, honoring its Doric heritage. During the Hellenistic period, the island became the primary naval base for the Ptolemaic kings of Egypt.

The Delicate Women

It is not only the indications of a flourishing civilization, the way the inhabitants of prehistoric Thira lived, and their cultural footprint, but also the proof that their artistic mastery makes them, as stated by the head of the Cycladic Antiquities Department, Dimitris Athanasoulis, creators of the oldest surviving complete works of painting in Europe.

Furthermore, there are so many depictions of women adorned with intricate jewelry, beautiful attire, and strong characters, like the Minoan women, that provide us with information on how women lived at the time. In fact, we recently had the opportunity to see one of the most impressive frescoes up close at the exhibition “Cycladic Women” at the Museum of Cycladic Art. This particular section of the fresco, featuring three women, reveals much about the customs and cultural norms of the era, captivating visitors: on the left, the woman with the necklace, who is the central figure with particularly developed breasts and impressive hair, wears an extravagant necklace that suggests she probably belonged to a higher social class. To the right stands the peplos-wearing girl with a shaved head, but the real star of the scene is the wounded woman in the center.

Her blood, which falls to the ground, gives rise to a crocus flower, emphasizing both the healing properties of the plant and the birth caused by this initiation ceremony. Nanno Marinatos, in her book “Akrotiri”, extensively discusses these ceremonies, drawing attention to the hairstyles of the women which reveal much. The most initiated women have full hair, while the younger ones are shaved. These initiation ceremonies are not related to marriage but rather to more religious matters, as they were not dominant rites—the most important were the initiation and transition ceremonies.

The Renovated Museum

Most of the frescoes from Akrotiri are housed in the renovated Museum of Prehistoric Thira, which remains open, apart from the well-known ones that are featured in the Thira Hall at the National Archaeological Museum. As for the fresco from the Adytum, it dominates the “Cycladic Women” exhibition at the Museum of Cycladic Art in Athens, along with the impressive Thira girl, which was found lying on her back by the excavator Charalambos Sigalas and is one of the three known “Daedalic Maidens” from 660-650 BC.

This towering (standing at 2.50 meters) aristocratic figure from Thira will return to her birthplace along with all the findings from the exhibition. These will inaugurate the under-renovation Archaeological Museum in Thira, which will house priceless treasures spanning the entire range of antiquity, from the Geometric Period to the Roman era.

The inauguration is expected to take place, according to reports, in the early summer, marking a positive sign for the symbolic restart of the island and a strong proof that the culture of Thira remains elevated and unyielding, despite the destruction and difficult conditions in which it flourished. It was destined to confront the elements of nature that made it so uncompromisingly astonishing and dominant throughout the world.

Ask me anything

Explore related questions