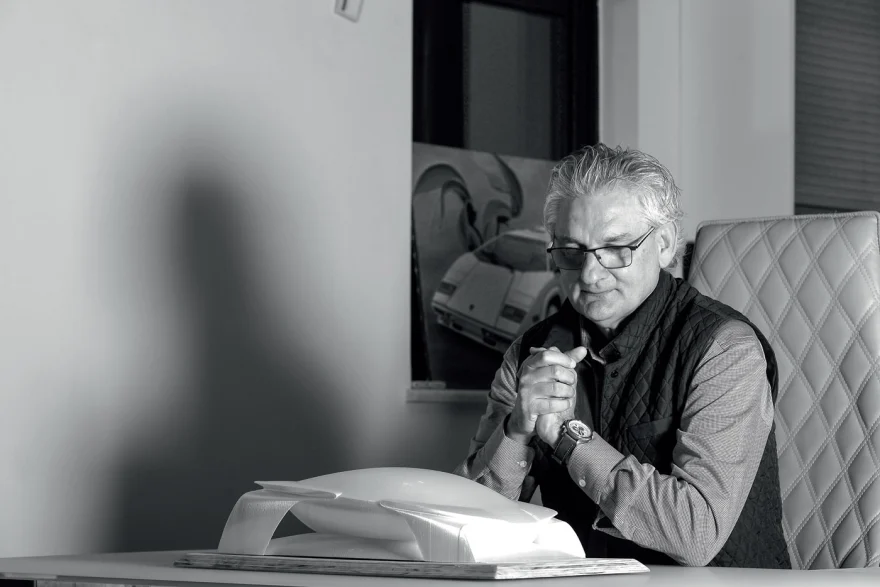

Sotiris Kovos reveals the secrets to his success, why Greece is an eternal source of inspiration for him, and how he envisions the car of the future, as well as a project he’s currently working on. He believes that in the future, driving lessons will be something done only as a hobby, as vehicles will no longer require drivers. He also discusses why Greeks are so demanding and bold when it comes to choosing their cars.

Vasilis Tsakiroglou: There are two aspects that make you a particularly unique designer: First, the cars you’ve designed have sold over 10 million units. Secondly, your first degree is in Sociology. Do these two characteristics combine in your work?

Sotiris Kovos: I believe they do because studying Sociology provided me with the intellectual tools to better understand and analyze the trends that emerge in human environments. It helps me more accurately grasp what the public wants, both their practical and aesthetic needs. On the other hand, no one starts out by saying, “Let me design a model that will become a global bestseller.” You always start with the goal of designing a beautiful car, a vehicle that makes people feel good—whether they drive it or simply admire it from the outside. Above all, cars should be viewed as moving sculptures. Not everyone needs to own a Ferrari or a Lamborghini, but when we see such exceptional vehicles on the road, it stimulates our senses and lifts our spirits. Beautiful cars brighten our lives, giving us joy because they play such a big role in our everyday existence, influencing how we develop our aesthetic criteria and tastes.

V.T.: How has being Greek influenced your approach to design, style, and aesthetics?

S.K.: In terms of pure design work, I honestly can’t pinpoint specific elements that are directly linked to my Greek heritage. Greece is inside me, however, as a spirit of freedom. Everything the Greeks have achieved, from ancient times to the present, is due to the fact that they never accepted limits on their thinking. And with the Yaris, for example—the original 1998 model—I designed it with complete creative freedom granted to me by Toyota. I didn’t consciously draw inspiration from anything specifically Greek, but rather from a universal motif. Specifically, I was inspired by the posture of an athlete on the starting blocks, ready to begin their race, embodying the explosion of energy and synchronization seen in sprinters.

V.T.: The first Toyota Yaris revolutionized the car industry; it was unexpected and revolutionary, as before then, supermini cars often looked like boxes on wheels. Since then, you’ve designed many vehicles—cars with 2, 4, or more wheels, and even yachts. Many of them have had great success, for prestigious companies such as Toyota, Lexus, and Suzuki. Is there a common characteristic in all your works?

S.K.: While it may sound abstract, my primary aim is to give every car I design a unique character, to make them stand out. That’s why I always try to create something different. Whether I succeed or not, that’s for others to say. The Yaris, for example, is a great example because it had a groundbreaking shape, a character that was unlike anything else on the market at the time. It was completely different in terms of proportions and details. The Lexus SC 430, even after two decades, is still considered a beautiful car. I was recently driving the Lexus GS, and someone on the road asked, “Is it new?” I designed it in 2002. For me, this was a reward because it shows that, in the eyes of an ordinary person, it’s a design that has stood the test of time, which is very important—and very difficult.

V.T.: One of the dominant trends today is SUVs, which weren’t as popular 20-25 years ago. Back then, the trend was more about MPVs—relatively large family cars like small vans, without much aesthetic attention. What do you think changed in car design during this time?

S.K.: Today, SUVs dominate, which is very interesting because this type of body style didn’t become popular because it answered different societal needs. I would say that SUVs mainly address psychological needs—people want to feel powerful, imposing, as though they are dominating others through the car they drive. That’s why people today want bigger SUVs.

V.T.: Isn’t it paradoxical that while the number of vehicles on the streets increases, thereby limiting available space, at the same time SUVs (and other vehicles) keep getting larger?

S.K.: Yes, exactly. But reality is always more complex. Today, for example, our lifestyle requires more space inside the car we drive. However, most SUVs don’t offer more space than station wagons, which have almost disappeared from the streets because they’re no longer in fashion. So, why are SUVs so popular? The only practical advantage they have is better visibility. But how is it that you have better visibility in an SUV when most people around you are also driving SUVs? The issue here is that the car is a symbol—it makes you feel better, just like clothes make many of us feel more attractive and boost our confidence. Without being sexist, this is especially true for women, who are often socially pressured to pay a lot of attention to what they wear. From this perspective, are high-heeled shoes practical? Certainly not. But they make the woman wearing them feel better. The same goes for SUVs. Yes, you sit higher and more comfortably, but the center of gravity is also higher, which isn’t ideal for stability and handling. SUVs are also proportionally heavier, so they consume more fuel. Yet, people still prefer them.

V.T.: Have Greek preferences changed over the last 20-25 years?

S.K.: Greeks have always been unique in their car choices—demanding and bold. It’s hard to fit them into molds. I would say that Greeks want to shout that they are different. They also want to feel proud of what they are and, by extension, what they drive. On the other hand, I’ve lived abroad for 33 years, so I haven’t been able to closely follow the trends in Greece over the past two decades. But one thing I can say with certainty is that the Greek market is more open to extreme design features and radical, unconventional models, such as some electric vehicles from Chinese manufacturers. This is a good thing because these cars are indeed groundbreaking in terms of design and quality.

V.T.: Despite occasional discussions and plans for various projects, Greece has never had a significant presence in the automotive industry, either in terms of car manufacturing or motorsports. Doesn’t this seem somewhat contradictory, given the passion Greeks have for cars and motorcycles?

S.K.: Yes, but we shouldn’t overlook that in our automotive culture, there’s the tradition of the Acropolis Rally, our national motorsport event, which strongly influences our interest in sports cars—particularly classic models from the ‘70s and ‘80s like the Lancia Stratos, Ford Escort, Opel Ascona, etc., all of which I loved as a child. These cars inspired me to become a designer. Feeling proud is important for us, wanting to feel that we are prominent on an international level. That’s why the Acropolis Rally is somewhat like tennis, which we recently “discovered” thanks to Stefanos Tsitsipas and Maria Sakkari. Before, few people watched tennis, but now, because of these two, we’ve all suddenly become tennis fanatics and, naturally, experts. Something similar happened with basketball, too. At the same time, Greeks remain loyal to classic brands and iconic models. Like the Alfa Romeo Giulia or Renault 4 and 5, which are making a comeback as electric cars, both identical and different from their original versions. Personally, I really like them.

V.T.: What do you think of the trend to revive older models, but in a modern version?

S.K.: It’s a complex issue. For example, the modern Ford Puma has nothing in common with the original model, but it’s a nice, well-designed car, despite the name being the only thing retained. The Renault 4 and 5, which I mentioned earlier, follow a different approach, maintaining the original shape in a modernized version. If we look at recent history, in the past 20-25 years, the Mini was very successful, while the VW Beetle revival failed. Why did the Beetle revival fail? Personally, I believe it was because of its packaging—too limited in space. You can’t have a car today where the back seats are uncomfortable. There needs to be a balance between classic proportions and modern, real-world needs for those who will use the vehicle.

V.T.: Isn’t it also a matter of cost? Aren’t cars today generally very expensive?

S.K.: Staying with classic shapes, reviving an older model doesn’t necessarily mean it has to be expensive. The Beetle was a car for the people, and that’s why it sold millions of units. The same goes for the Fiat 500. So today, these cars should remain affordable, not because something is “classic,” should we add an extra 30% to its price.

V.T.: Is the future of automotive industry electric?

S.K.: Personally, I have no doubt about it. But I would say that even now, the present is electric. In the beginning, electric vehicles had a strange, odd look, purposely

Ask me anything

Explore related questions