“Son, where are you going?” – “Mother, I’m going to the ships.”

This line by poet and sailor Nikos Kavvadias encapsulates an entire era—when shipping was an escape route for thousands of young Greeks seeking work at sea.

But times have changed. Modern life, new habits, and different dreams mean that Greek youth no longer dream of sailing off. And so, the country became… off-deck: from 120,000 sailors in the 1970s, only 25,540 remain today.

Where Do Today’s Sailors Work?

According to a study by the Seamen’s Pension Fund (NAT)—Greece’s oldest fund—there are 25,540 registered sailors today. In 1970, over 120,000 Greek sailors were registered. Even though there was a 5.7% increase in seafaring employment from 2022 to 2023, it’s not enough to meet the growing needs of the Greek-owned fleet.

In 2023:

- 10,521 sailors worked on passenger ships

- 7,814 on tankers

- 5,469 on cargo ships

Regarding ranks:

- 1,292 were senior officers (captains and chief engineers)—up 60% from 2020

- 3,271 were cadet trainees, 10% of whom were women

Of these cadets:

- 2,543 worked on Greek-flagged or NAT-contracted foreign-flagged ships

- 728 applied to redeem time served on non-contracted foreign-flagged ships

Why Are Fewer Young People Choosing the Sea?

The easy explanation? Today’s youth “don’t want to ruin their comfort.” They won’t isolate themselves on a ship for months, away from home and their lives. They’ll choose a land-based job, even if it pays less—preferring the security.

But it’s more complex.

Retired commercial sailor Mr. Tsagaris notes that although technology has improved safety and communication, it also introduced new challenges:

- Longer working hours

- Many companies keep sailors onboard longer than the 6-month contract limit

- Short port stays—little to no shore leave

- Even with internet onboard, it’s often very slow

He adds:

“Being a sailor has always been hard—then and now. I’d say today there’s little left of the profession’s former allure. But the economic incentive still remains—then and now—it’s often about the money.”

Every Port, a Heartache

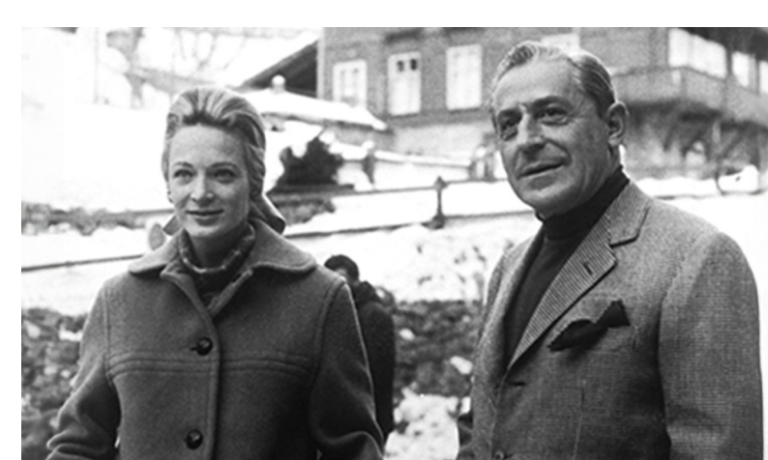

In the 60s and 70s, seafaring offered an escape from poverty and desperation, but it was no easy life. Everyone sought a connection (a “good middleman”) to get hired as a rookie on one of Niarchos’, Latsis’, or Onassis’ ships.

Ships back then lacked comfort and safety, especially those from smaller or foreign companies that didn’t prioritize crew wellbeing.

What security could a wooden vessel in stormy seas offer—or a steel ship with primitive technology?

Harsh Truths & Strange Wonders

Captain Stelios, now retired, recalls his first contract: 23.5 months at sea.

“My first flight ever was to Egypt, then on to India. From there we sailed to South Africa during apartheid. I saw things you wouldn’t believe—black workers in chains, like in the movies, forced to shovel coal in the ship’s hold.”

It wasn’t all “every port a love story.” There was danger, loneliness, and family anxiety that their loved ones might never return.

Hardships of the Old Days

Veterans recall how captains—often ship shareholders—cut costs, leaving crews hungry. Meals were as small as 200 grams. Fights over food were common.

Post-WWII seafarers were often tough, battle-scarred men, many of whom had survived torpedo attacks during wartime and faced new dangers with unnerving calm.

Water shortages were also frequent. Ships might carry enough for 10 days but sail for 15. Sailors had to go days unwashed to conserve water.

Privileges

Naturally, working and safety conditions have improved and are light-years away from what the older generations of seafarers described. As Korean, Japanese, and Chinese shipyards compete fiercely to secure the largest share of orders from Greek shipowners, the ships they offer are increasingly safer, more efficient, and more comfortable.

This means that newer generations of seafarers enjoy different privileges. With the aid of advanced technology, the massive ships that carry everything the world needs to keep going can sail through typhoons and tropical storms, defying waves as tall as apartment buildings and winds strong enough to uproot everything in their path.

But even if disaster strikes, beyond constant communication with the mainland and security services—as well as nearby ships—seafarers are no longer forced to escape in wooden boats like in the old days. Instead, they evacuate to armored, enclosed, fireproof, unsinkable lifeboats or wear special suits (the so-called “immersion suits”) that keep them afloat and protect them from hypothermia for hours, until help arrives.

Crews now have real-time weather updates at their fingertips and hourly communication via satellites and the Internet—even if they are at Point Nemo, the most remote spot in the ocean where the closest human is on the International Space Station rather than any landmass on Earth! Even the crew cabins—now air-conditioned—bear no resemblance to the bunk beds of the past, with their filth, deprivation, and cramped quarters. Seafarers now enjoy all the comforts they would have in their own homes.

Of course, it’s not just the improved conditions aboard ships—comfort, safety, and good pay. Nor is life at sea today all smooth sailing. Studies by NGOs—especially at a time when wages remain stagnant and inflation is skyrocketing—show that seafarers, not just Greeks but also those from other European countries, face a host of problems. Among them are increased workloads, fatigue, and high demands—including bureaucratic ones—in an environment often described as lacking “empathy” and marked by “social isolation.”

Bullying on Board

Due to the variety of nationalities and cultures that make up ship crews today, and the fact that women now also work on ships, incidents of bullying, harassment, and even sexual assault during voyages are on the rise. This is, after all, one of the reasons why, combined with the lack of guidance policies and medical prevention, cases of depression aboard ships are increasing—driven by isolation, intense work pressure, lack of recreation, and stress.

Added to these issues are the growing efforts by some shipowners to convince seafarers to stay on board for longer periods, due to the replacement difficulties left in the wake of the pandemic and the skyrocketing cost of freight rates.

Challenges are also reported regarding food on board, including insufficient food budgets, poor food quality and hygiene, lack of cooks, and the absence of nutritional training by the shipowning company—vital for keeping seafarers’ bodies and minds healthy throughout their time at sea.

Ask me anything

Explore related questions