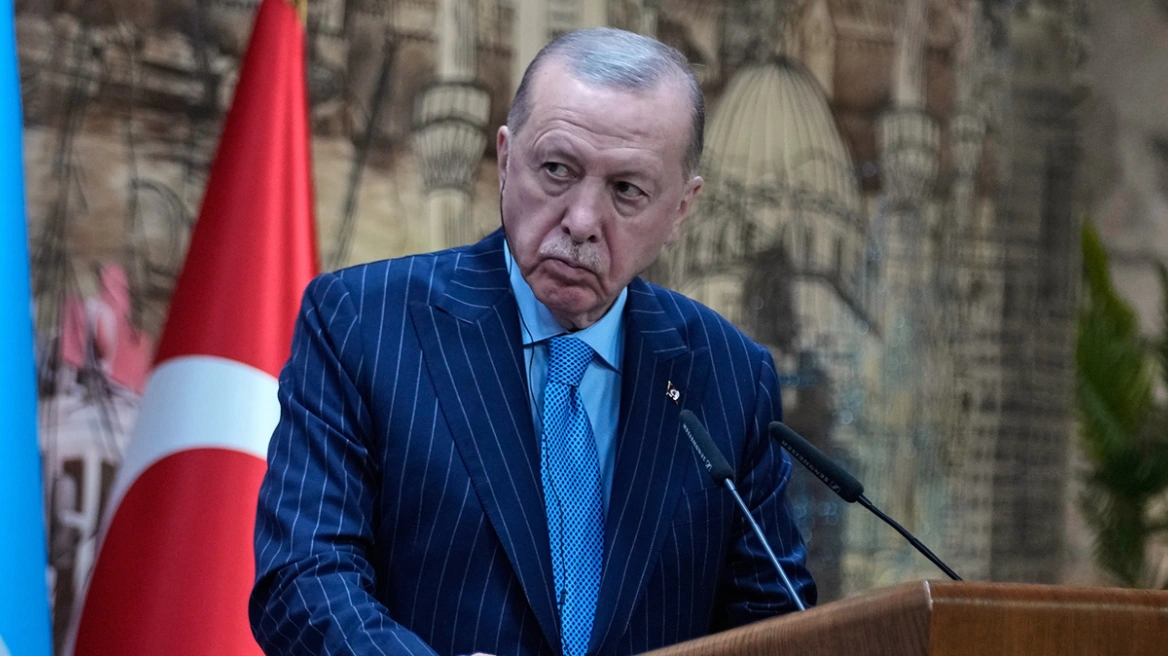

The impact of our demographic developments on age structures, and in particular on the changes in the number and specific weight of two large age groups: the 20-64 and the 65 and over age groups, is examined in the latest publication of the Institute for Demographic Research and Studies (Demographic ageing, working age population and employed persons in Greece at the 2050 horizon), which is signed by the retired professor of the University of Athens. Vyronas Kotzamanis, retired professor of the University of Thessaly and director of the Institute of Economic and Social Research (IDEM).

Kotzamanis examines in particular the future evolution of the 20-64 age group (the working-age population), its impact on the working population and on the ratio of workers to those aged 65 and over, who are taken as “dependents” (although this is only partly true as not all 65+ are – and will not be in the future – outside the world of work).

The expected medium-term significant decline in the 20-64 age group is mainly due to the shrinking intergenerational fertility as those of the pre-war generations who had children in the early post-war decades had an average of 2.2 children, those born around 1960 had 2 and those born around 1985 had less than 1.5 children per woman. This was also reflected in declining births after 1980, a decline that accelerated in the last fifteen years as the population of women of childbearing age declined significantly (a trend that is not expected to be reversed in the coming decades). This decline in births led first to a decline in the 0-19 age group, then in the young population of productive and reproductive age (20-44 years) and finally in the 45-64 age group, while the influx of economic migrants into the country after 1990 merely slowed the decline in the 0-64 age group.

And at the same time, Mr. Kotsamanis says, there has been a steady increase in the 65 and over age group, an age group that originated from the pre-1980s large births, while at the same time benefiting from the significant increase in life expectancy, the result of a significant reduction in mortality after 1950. The acceleration of the demographic ageing recorded in the last fifteen years was also due to our immigration balance (more exits than entries in our country), as immigration was mainly of young people aged 25-45, both Greeks and foreigners who settled or were born in Greece in the previous decades. The debate and concern surrounding this exodus, Kotzamanis says, unfortunately focuses on only one of its components – the “brain drain” of mainly Greek nationals – although a large proportion of those who left our country after 2000 are Greeks and foreigners with relatively low and medium levels of education, resulting in the gaps that have recently appeared in certain sectors of economic activity.

The growing group

The group aged 65 and over, based on Kotzamanis’ analysis, is the only group that will grow in the future (they will constitute more than 1/3 of the country’s population in the early 2050s compared to 24% today), while the total population of Greece is expected, if the immigration balance is zero, to decrease by 1.3 to 1.5 million between 2025 and 2050. This reduction will result from the shrinking of the younger 65-year-olds and, in particular, the largest part of them, the 20-64 year olds.

And given the expected significant decline in the 20-64 age group (around 1.7 million if the migration balance is zero over the next twenty-five years), Mr. Kotzamanis poses and answers the following question: is it possible – and under what conditions – that the number of employed persons in this age group will remain at the same level in 2050 as in 2025 (4 million)? This target, if set, can be achieved under two conditions:

The employment issue

Increasing the very low rate currently in employment of 20-64 year olds due to the extremely low participation rates in employment of both women in all age groups (we have one of the largest participation gaps between the two sexes points out) and both sexes in the 20-29 and 55-64 age groups) to the high unemployment rates. If this rate progressively increases from 67% today to 82% in 2050, the expected reduction in the number of 20-64 year olds in the workforce in 2050 will be significantly reduced. In particular, in this case, even if the 20-64 age group decreases by 1.68 million (from 5.95 to 4.27), the number of workers in this age group will amount to 3.5 million in 2050 compared to 4.015 million in 2025 (-515 thousand). In this favourable scenario, there would be 1.1 employed 20-64 year olds per 65+ (3.5/3.15) instead of 1.6 today.

A positive immigration balance over the next twenty-five years of around 700,000. A balance of this magnitude (+28k/year averaged over twenty-five years), which remains much lower than the 1991-2010 period (40k/year), would limit the decline in the total population, 20-64 years old, and increase the workforce by 500k. In this case, the number of people employed in 2050 would reach 4 million (almost as many as today), and there would be 1.24 employed 20-64 year olds per 65+ (3.90/3.15) compared to 1.64 today (4.015/2.45 million).

A possible positive immigration balance of this magnitude, Kotzamanis says, would also have a positive impact on “demography”, as part of the surplus of inputs over outputs would be made up of young people, not only of productive but also of reproductive age (25-49 years old). They would slow down demographic ageing and the decline in the number of people of childbearing age (women aged 25-49 are expected, if the migration balance is zero, to fall by 465 thousand between 2025 and 2050, i.e., by -28% ), with a positive impact on births.

The changes

Of course, even if this target is reached, the current ratio of employed to people aged 65 and over (164 employed per 100 older people today) will change, as in 2050, there will be just 124. In the absence of other changes, this change will have multiple impacts and calls for a series of interventions in many areas, aiming not only to mitigate but also to reverse the negative effects of our demographic developments.

Speaking to the Athens-Macedonian News Agency, Mr.Kotzamanis stresses, among other things, that the wealth produced and “captured” by a country to meet its needs in many areas (and not only for pensions, which is the main focus of the public debate) does not only depend on the population of workers. It depends on the “quality” of human resources as well as on several other parameters, many of which have been mentioned for many years both in the reports of the Bank of Greece and the KEPE and the reports of all international organisations on the Greek economy.

Ask me anything

Explore related questions