The lifelong relationship between Nikos Kazantzakis and Greece’s first female philosopher is vividly reflected in the hundreds of letters he wrote, which were auctioned on Tuesday. These include deep confessions of love and admiration, descriptions of their travels, and how he incorporated his beloved into his epic work Odyssey.

Any illegal use or appropriation of this material in any way is strictly prohibited by intellectual property law, with severe civil and criminal penalties for violators.

“My beloved Mundita”: The love letters of Nikos Kazantzakis to philosopher Elli Lampridi

“A woman must be loved so deeply that she never even gets the idea that someone else might love her more!” Nikos Kazantzakis once said, capturing in words the high regard he held for women in his life, even though some have characterized his depiction of women in his work as ambivalent. He connected deeply with remarkable women, loved them profoundly, was inspired by them, and surrendered to love — which he described as “like ether, harder than steel, softer than the wind that opens, penetrates everything, leaves, escapes…”

“My beloved Mundita”: The love letters of Nikos Kazantzakis to philosopher Elli Lampridi

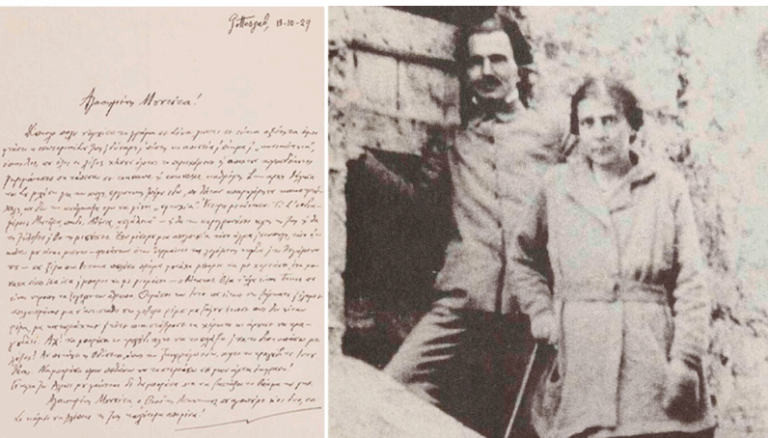

Nikos Kazantzakis with Elli Lampridi

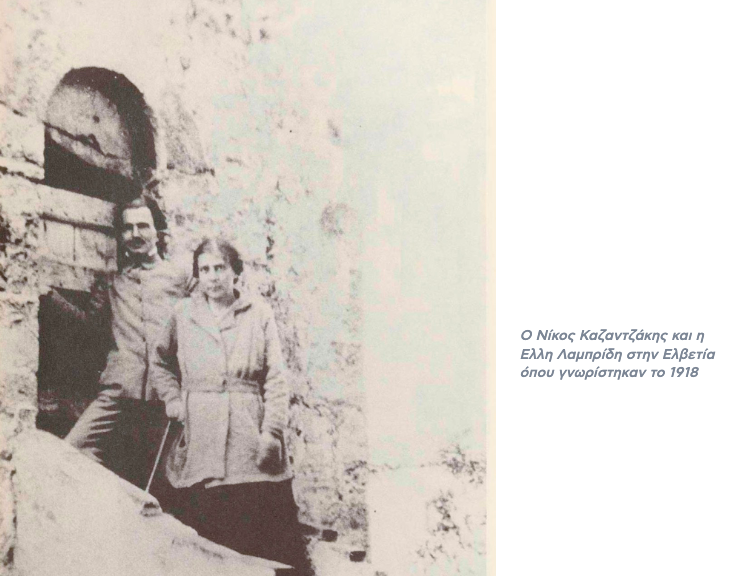

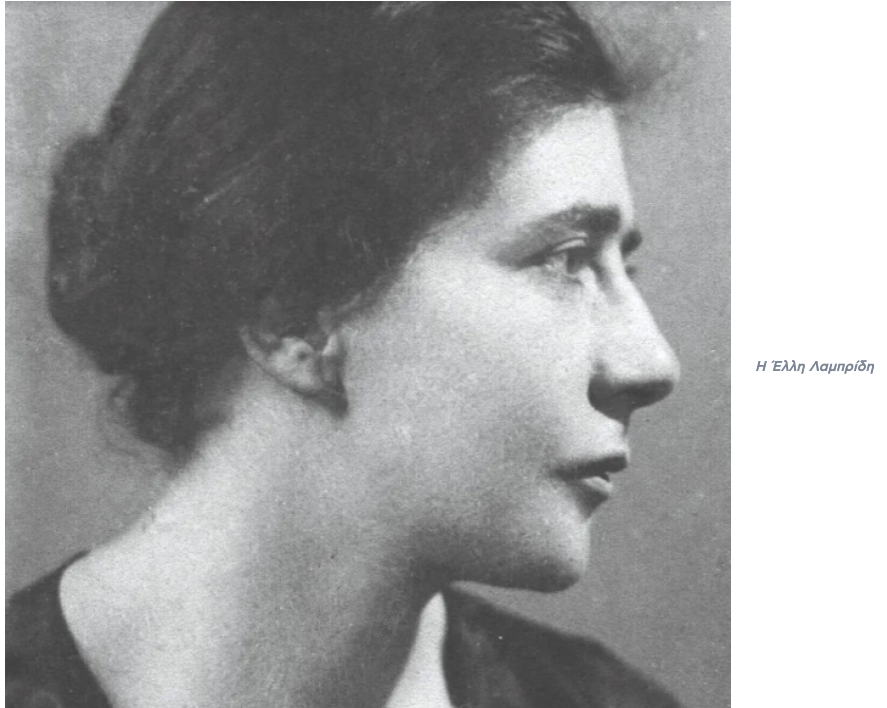

One of the most significant women in his life was Greece’s first female philosopher, educator, book reviewer, columnist, and translator, Elli Lampridi. They first met in February 1918 in Switzerland. At that time, he was still married to his first wife, author Galatea Alexiou, and she was studying Pedagogy on a scholarship. Their shared intellectual depth, unconventionality, and common interests immediately drew them together. They became a couple and lived together for eight months. After their breakup, they kept in touch until 1927, when they reconnected for about a year. Later, their relationship evolved into a deep friendship and spiritual connection that would last their entire lives.

The letters

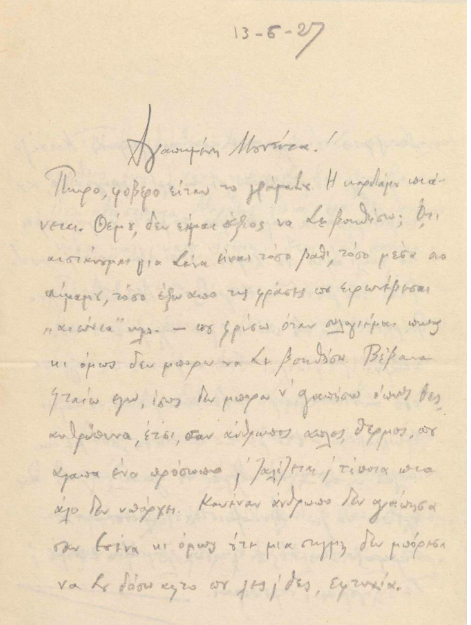

The complex, lifelong bond between Nikos Kazantzakis and Elli Lampridi is documented in dozens of exchanged letters. Of these, 86 letters written from 1927 to 1952 were auctioned on Tuesday by the Vergos auction house, alongside other rare books, manuscripts, documents, and engravings. Their estimated combined value, including the publication Correspondence with Mundita (MIET, 2018), was between €12,000 and €16,000, but so far, no buyer has been found.

“My beloved Mundita”: The love letters of Nikos Kazantzakis to philosopher Elli Lampridi

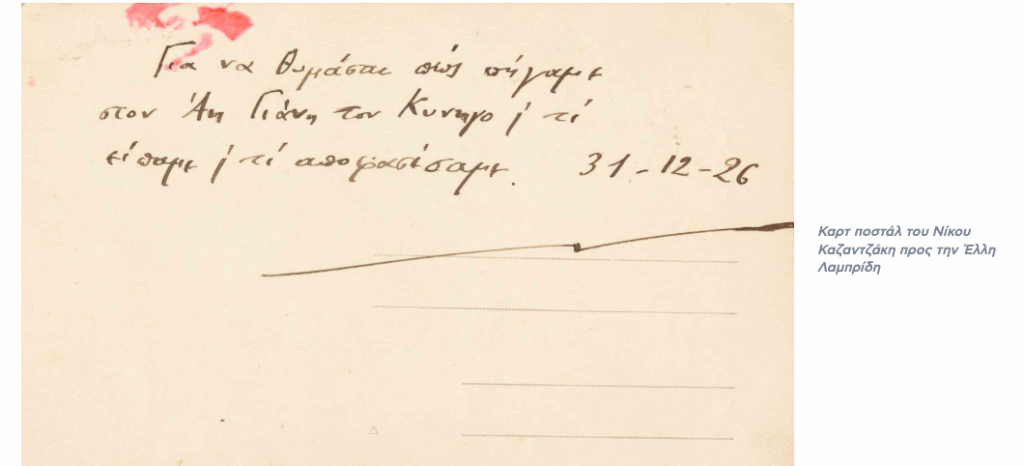

Postcard from Nikos Kazantzakis to Elli Lampridi

Reading these letters reveals many interesting details not only about their relationship but also about their personalities, lives, and the circumstances of their creative work. Kazantzakis’ admiration and deep love for Lampridi were perfectly expressed through the nickname he used in their correspondence: Mundita, a word from Buddhist philosophy meaning the selfless joy for the good fortune of others. His love for her was so profound, and her influence so strong, that he even included her in his works. In his epic poem Odyssey (which he wrote with a lowercase o), he depicts her as a leopard. His beloved is “the olive leopard, the three-headed virtue, fire, beast, brave-hearted!” as he reveals in a letter he sent her in August 1927:

“My beloved, if someone were to analyze your letter, they would find it as rich — as the soul of a great person: rage, love, hatred, lofty concern, injustice, tenderness, heart, mind, imagination — everything. I found myself completely alone, in a moment of creative intensity — even though today is Sunday, I decided to write to calm my bitterness, since my vain hope for your arrival here was disappointed. And behold, you came furious, all claws, teeth, movement — a “lioness.”

And I was struck with an intense desire to give Odysseus a single companion in the desert, in his journey and in the destruction of my city — a leopard. She will always be with him, love him, and sharpen him, fill him with wounds and caresses. That’s how I found a way for you to enter the Odyssey, because until now, I couldn’t see you as a woman in it. This will happen in the second draft. Still, I marked in various places where and how you will intervene — hurting or loving, or both at once.”

About a year earlier, in July 1926, Kazantzakis published an article in Eleftheros Typos titled “Mundita and I”, which even served as the catalyst for their romantic reconnection. Lampridi, born Elli Lampridi, also appears in other works by the great writer, such as in the dedication to his play Nikiforos Fokas (1927) and in his book Traveling (1927), which contains a letter to “Beloved Mundita.”

“My beloved Mundita”: The love letters of Nikos Kazantzakis to philosopher Elli Lampridi

Nikos Kazantzakis and Elli Lampridi in Switzerland, where they met in 1918

Travel diaries

One of Kazantzakis’ greatest, most incurable weaknesses was travel. He documented the sights he saw and the feelings he experienced during these journeys in letters to his then-beloved, which read like personal diaries.

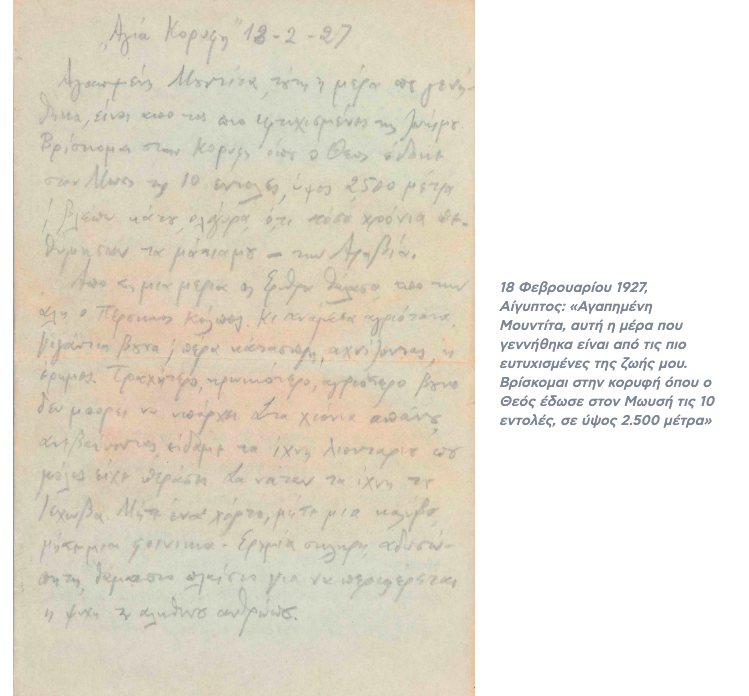

On February 18, 1927, his 44th birthday, he wrote her spellbound by Egypt (in modern Greek):

“Dear Mundita, this day of my birth is among the happiest of my life. I am standing at the top where God gave Moses the Ten Commandments, at an altitude of 2,500 meters! I see below and all around what my eyes have yearned for all these years — Arabia. On one side the Red Sea, on the other the Persian Gulf. Between them, wild, giant mountains, and beyond that, the desert — stark white, steaming. No more heroic, wild mountain exists. As we climbed the snow, we saw the footprints of a lion that had just passed. It’s as if they were the footprints of Yahweh. Not a blade of grass, not a hut, not a palm. A harsh, relentless wilderness — a magnificent setting for the soul of the true human.”

“My beloved Mundita”: The love letters of Nikos Kazantzakis to philosopher Elli Lampridi

February 18, 1927, Egypt:

“My beloved Mundita, this day of my birth is among the happiest of my life. I am at the summit where God gave Moses the Ten Commandments, at 2,500 meters high.”

A few months later, in the fall of 1927, Kazantzakis described his preparations for his eagerly awaited trip to Russia:

“I will leave on October 13. But with the storms now, I don’t know what time the ship will arrive. Anyway, I’ll be in my cell at 3 pm, and then around 5, I’ll have many tasks: passports, newspapers, etc. If you can come, I’ll leave the key in the usual place. The mattress will be sent by telegram to Piraeus, and I’ll tell you where it can be picked up. I haven’t seen the courier yet, so I haven’t coordinated. I’m glad I’ll see you soon and very much. I fear I might not be allowed to leave for Russia. We’ll see. Kisses, dear Maya! N.”

This trip, which he longed for so much, eventually took place and lasted three full months, from October to December 1927.

“I am filled with despair”

After their definitive separation, Kazantzakis continued to write letters to Lampridi. In October 1929, from Czechoslovakia, he opened his soul wide open, as if filled with darkness:

“My beloved Mundita! Very difficult to start a letter to you because your inner life has reached such intensity — strength, faith, disbelief, bitterness, “cynicism,” as you say — that all words lose their meaning or acquire unexpected grimaces, as if fallen into a hollow or convex mirror. At first, I wanted to tell you about my working life here, which would be unbearably rugged if I didn’t force it to become “happiness.” Later, I regretted it. Why does it matter to you? Mother, child, Athens, “security” — either you despise this life or envy it or hate it. Inside me, there is a despair so fierce, silent, so everything I do feels hateful — especially when it warms what’s called the heart or the mind — I now know for sure that only one thing can satisfy me, one thing is just enough or can fill me — death…”

He concludes poignantly:

*”My beloved Mundita, may the “God” of *Asceticism* that we both love make you see life better than I do!”*

“My beloved Mundita”: The love letters of Nikos Kazantzakis to philosopher Elli Lampridi

October 18, 1929, Czechoslovakia:

“My beloved Mundita! Very difficult to start a letter to you because your inner life has reached such intensity — strength, faith, disbelief, bitterness, “cynicism,” as you say — that all words lose their meaning…”

Preparing for the Nobel

Although Kazantzakis’ romantic relationship with Lampridi definitively ended in January 1928 — by then, he had already met his future second wife, Eleni Samiou — their regular communication continued. They collaborated closely on translating and promoting his books internationally, and on his Nobel Prize nomination, which, unfortunately and unjustly, was never awarded.

In summer 1943, from England, he wrote to her:

*”Still, I beg you sincerely: Today I received a letter from Sweden saying they haven’t yet received the *Odyssey* that was sent from Athens (three months ago) for the Nobel. So, it’s urgent to send immediately the Waterlow copy (by British diplomat, ambassador in Athens from 1933 to 1939) — take it and tear the page with the dedication, and write: To the Swedish Academy, Nobel Prize in Literature, in English, and below my name in capital letters so my handwriting isn’t obvious. When that’s done, coordinate with Wallare on how to send it immediately and securely to Stockholm. You understand how important this is to me, and please don’t neglect it for a single day. Make sure the Odyssey arrives there as quickly as possible. Please, I beg you. And write to me immediately once it’s done, so I can rest. Always yours, daragaya maya! N.”*

Elli Lampridi

Born in Athens in 1896, the daughter of lawyer, journalist, newspaper publisher, and politician Ioannis Lampridis, and Athens-born piano teacher Eleni Fotiadou, Elli Lampridi grew up in a fertile environment with many intense interests. Her strong character was evident early on; she insisted and eventually managed to attend a boys’ high school — the only way later to gain admission to university.

She studied initially in the Department of Philology at the University of Athens and later Pedagogy in Switzerland. Over time, her focus shifted towards philosophy, which was a bold choice given the conservative views of her era.

From 1920 to 1923, she worked as a teacher in Constantinople, where she met Konstantinos Stylianopoulos, whom she married, and they had a daughter, Niki. The marriage ended prematurely, and her only child tragically died in 1945 from shrapnel in a British mortar shell.

Lampridi had just returned to Greece from London, where she had been since 1940, actively participating in anti-war efforts, giving informative talks, and raising funds for the Red Cross. Her anti-war actions cost her Greek citizenship, forcing her to remain “a prisoner” in Great Britain until 1960, when she finally returned permanently. Her life was difficult, facing financial hardships.

Despite this, she taught to make a living, translated, wrote philosophical books, essays, studies, and her autobiographical book Niki, named after her prematurely lost daughter. The dictatorship of the Colonels banned her from leaving Greece, and she passed away before she could see democracy restored.

Her relationship with Kazantzakis was decisive and lifelong; she never overcame it. Despite their bond, there were also many differences. She wrote after their breakup: “Kazantzakis was made to reconcile with a woman willing to renounce herself, adapt in his way, submit to his everyday life.”

Kazantzakis, however, deeply knew he couldn’t make her truly happy. He confided in a letter in June 1927: “Perhaps I can’t love as you want, humanly, simply, as a warm person who loves someone, gets dizzy, and nothing else matters. I’ve loved no one as I loved you, yet not a single moment could I give you what you say, what you want — happiness.”

Ask me anything

Explore related questions