The government’s new doctrine for illegal migrants arriving in Crete on fishing boats from Libya’s coasts can be summed up in one blunt message: “Do not come to Greece.” While the numbers don’t yet resemble 2015 — when nearly a million people passed through Greece to the rest of Europe and tens of thousands remained, eventually gaining residence permits after seven years of semi-illegal stay — the European context today is entirely different.

Since the winter of 2016, countries north of Greece began closing their borders. Following recent major electoral shifts in both Europe and the US, even countries like Germany — which initially welcomed Syrian refugees selectively, based on their professional skills — have now dramatically hardened their migration policies. Some are even seeking to return migrants to Greece if it was their first country of entry.

The primary reason for this shift continues to be immigration. This is why the Greek Prime Minister reassured Berlin via Bild by stating: “Greece is not an open corridor to Europe.”

At the same time, the arrival in Crete of thousands of young men — mainly from Egypt, Pakistan, and Bangladesh (countries considered safe, with no war or civil conflict, meaning asylum claims are ineligible) — has led to stricter policies. The goal is to create a strong deterrent effect: messages sent back by those detained in closed facilities with no hope of reaching Europe or staying in Greece to work will, it is hoped, discourage others from attempting the journey.

The Legislation

The hardening of policy is formalized today, Monday, with a bill tabled by Thanos Plevris, prepared by Makis Voridis, that includes imprisonment for those who refuse to return home after asylum rejection.

Meanwhile, Greece continues to seek cooperation — possibly even a repatriation agreement — with Libya, despite its chaotic state with two governments and many armed groups profiting from human trafficking across the Mediterranean.

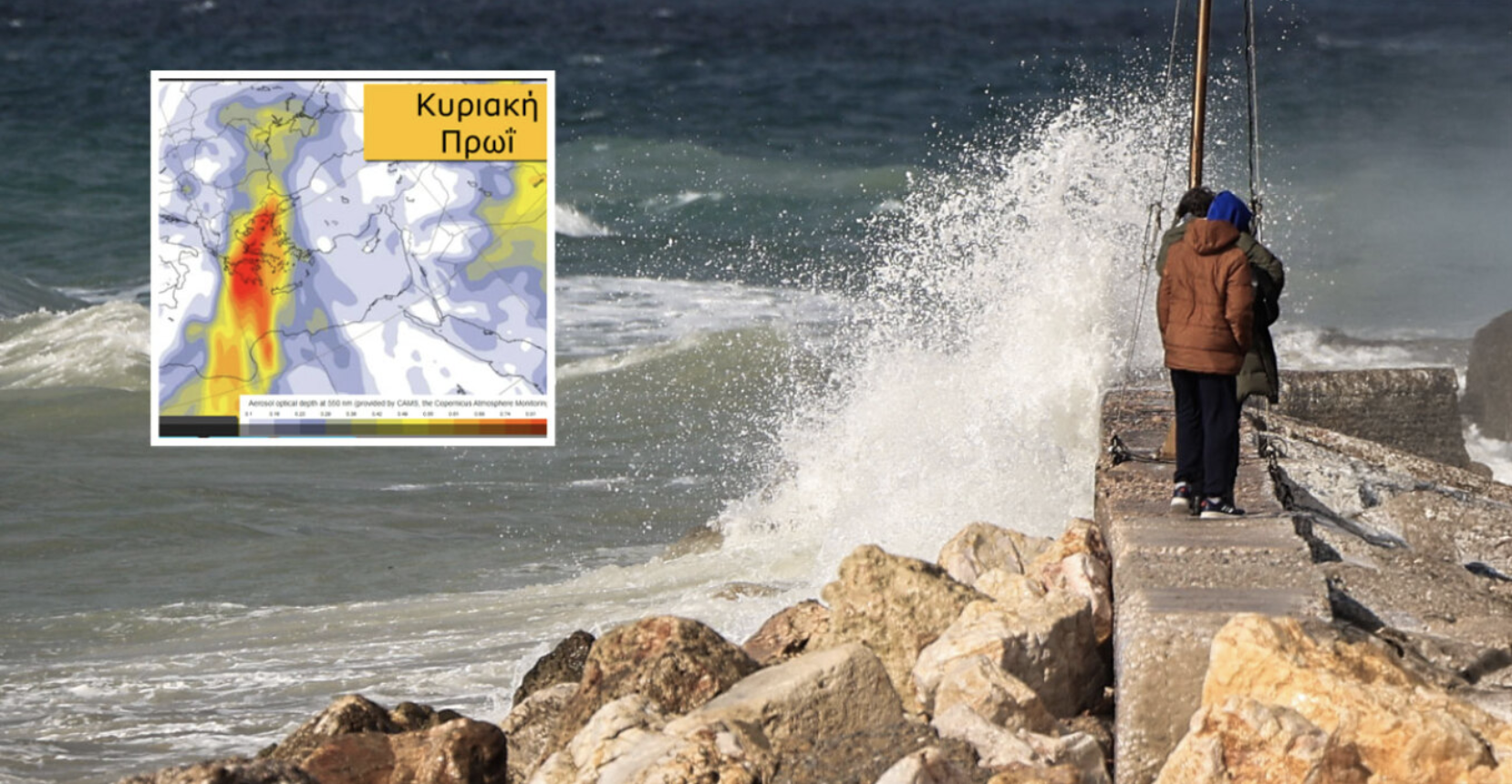

Boat trips from Tobruk and other ports under Marshal Haftar’s control in eastern Libya paused briefly last week due to strong winds but resumed on Friday when the weather calmed — bringing 507 more people to Crete, worsening the crisis on an island unprepared to handle such numbers.

Return to Libya

A new European delegation trip to Eastern Libya is scheduled soon. Haftar’s regime sees an opportunity: his best bargaining chip for international recognition is cooperation on migrant control.

According to The Economist, the migrants with the highest chance of reaching Europe are young, healthy men, not the vulnerable (women and children). From over 12 million Sudanese refugees fleeing civil war since April 2023, most children and teens are in neighboring countries like Chad. But 43% of those who made it to Libya are adult men seeking entry into Europe.

Sudanese refugees are eligible for refugee status — the horrors of their civil war may no longer dominate headlines, but testimonies remain chilling. However, under Greece’s new policy, even they will face a three-month suspension of asylum processing, though they will be held in separate areas from migrants with no hope of refugee status.

The Five Measures to Stop the Boats

Echoing the Evros border crisis of spring 2020, the government is adopting an even harsher doctrine, sending a clear message to tens of thousands waiting in Libya: don’t come to Greece.

Beyond tightening regulations and prioritizing deportations, the Plevris amendment — freezing asylum applications for three months — passed on Friday with 177 votes in Parliament. It sets a stronger precedent than even the March 2020 freeze for Turkish migration flows, which lasted only one month.

The tougher stance is driven by developments in Africa: economic hardship in Libya, civil war in Sudan, and poor living conditions in sub-Saharan Africa push mostly young men to attempt the dangerous journey. Libya, with its lawless state and numerous armed groups, has become the launch point.

A European source told To Thema that Tripoli’s government doesn’t even control its western port, which is dominated by militias. Similarly, Tobruk in the east is under paramilitary influence, though communication with Haftar is slightly better, as they “speak the same language.”

Stick Without the Carrot

Abandoning the usual “carrot and stick” approach used by many governments, Greece is now opting for “stick and more stick” — creating strong disincentives for migrants to make the costly, dangerous trip.

This shift is due to:

– The rapid increase in arrivals in Crete, overwhelming local capacity (with no reception or identification centers).

– The government’s political unwillingness to allow a repeat of 2015, even at a smaller scale, as European political and social sentiment has drastically changed.

As a top government minister told To Thema, “When Denmark enforces strict anti-migration policy, can we afford to play the EU’s good guys?”

Minister Thanos Plevris, in a statement to To Thema, confirmed that the asylum freeze and other tough measures were pre-agreed with the European Commission, hence no significant objections from Brussels.

“We’ve moved on from Merkel’s era of welcoming refugees. Now, we don’t want them to even consider coming,” said a government source, explaining the new doctrine.

On this line stands Kyriakos Mitsotakis as well, who once again chose to send a message to the German public through the tabloid newspaper Bild, known for its hardline positions on migration. “Greece is not an open transit route. The journey is dangerous, the outcome uncertain, and the money paid to smugglers ultimately wasted. Illegal entries will not lead to legal settlement. Our message is clear: Greece is not an open corridor to Europe,” he declared, while also stressing that a unified European response to the problem is necessary.

The implementation of the new doctrine—which admittedly has caused some discomfort even among New Democracy officials who held responsible positions under the previous system (e.g., Dimitris Avramopoulos, Sofia Voultepsi, Dimitris Kairidis)—is also being extended in practice to migrant facilities. It remains to be seen whether the freeze on asylum applications will be limited to a three-month period or will be extended beyond September, if the migration flows continue. Notably, in recent days, the flows have significantly decreased, although it remains to be seen whether this condition will be sustainable over time.

After all, Libya is a transit country and intends to remain as such, with local authorities making it clear to their European counterparts that they neither want nor are able to become… Turkey, i.e., to hold millions of refugees in exchange for financial compensation.

In Greece now, migrants arriving from the Libyan Sea will henceforth face direct deportation. They will automatically enter administrative detention and deportation procedures will be initiated. This of course requires better coordination with their countries of origin, such as Egypt, from which many flee due to the dire economic situation.

The Bill on Monday

Today, the Plevris–Voridis bill is being submitted to Parliament. At the same time, the bill increasing the period of administrative detention for undocumented migrants to up to 24 months will also be passed. Additionally, it stipulates three years’ imprisonment without suspension and a €10,000 fine for those who refuse to return to their homeland despite their asylum application being rejected. Moreover, the automatic legalization of undocumented migrants who can prove a seven-year stay in Greece is abolished.

Thanos Plevris has also announced a review of the benefits granted to asylum seekers from the national budget, as well as changes to the food menu in migrant facilities. Plevris is acting on the logic of limiting the choices available to migrants so that the facilities do not resemble a “hotel experience.” This move is mostly symbolic rather than cost-driven.

According to sources from Proto Thema, the leadership of the Ministry of Migration is also considering more active segregation of asylum seekers within or between facilities based on their profile. Practically, if someone has a higher chance of being granted asylum, they will be housed with others of a similar profile; conversely, those likely to be rejected will be grouped together. According to relevant officials, currently, about 10% of those entering the country are entitled to asylum, partly because more Sudanese are now arriving in Greece.

It’s also worth noting that Proto Thema revealed last Sunday the government’s intention to restrict asylum applications from Muslim Syrian nationals, given that Syria now has an active government.

Furthermore, Plevris’ policy direction is to tighten controls on individuals with identity verification issues, i.e., those arriving in Greece without the necessary documents. Legally, such individuals can be detained for up to 12 months, but this has not been enforced so far—a situation likely to change.

New Facility in Crete

The new plan also includes at least one new migrant facility in Crete. During a meeting on Friday at the Ministry of Migration with the participation of the Regional Governor of Crete Stavros Arnaoutakis and the President of the Regional Union of Municipalities of Crete Giorgis Marinakis, it was made clear that the decision to build the facility has been finalized. It was also explained that the center is not intended for long-term detention on the island but rather for reception and identification, after which migrants will be transferred to detention centers in mainland Greece.

The ministry leadership did not disclose the exact location of the new closed facility to local officials, but the decision appears set. The former Zografakis army camp in Kastelli, in the Municipality of Minoa Pediada, with an area of about 17 stremmata (approx. 4.2 acres), is considered the most likely site. The facility is planned to accommodate 3,000–4,000 residents.

The Economist’s View

Although there are already local reactions, the government’s plan remains unchanged. The African populations being moved now include individuals from Bangladesh and Pakistan, who arrive by plane in Libya under the pretext of working and then try to cross the sea into Europe. Given this, many in Europe believe that cooperation with third-country governments should be systematized so that asylum processing centers can be established in North Africa. Europe would then accept only those who are legally granted asylum.

“We want this and are trying to achieve it, but African countries don’t want to keep these people,” a European source notes. Of particular interest is the front-page article of the British magazine The Economist, which points out in its latest issue that the current asylum system has essentially collapsed, and Western governments must focus on caring for refugees near their countries of origin.

“Voters have made it clear they want to choose who to let in—and that does not mean everyone who shows up asking for asylum. If rich countries want to curb these arrivals, they need to change the incentives,” the magazine emphasizes.

A Message of Zero Tolerance

The government is sending a zero-tolerance message to human trafficking rings that send illegal migrants through Libya to Greece. The adoption of the new doctrine is tied to the changing reality that turns Greece into a ‘warehouse of souls’, since it is the first country of entry.

Ask me anything

Explore related questions