The legal recognition of the Bektashi-Alevis in Greece as a private religious legal entity essentially makes a tiny minority Muslim community officially visible. However, the Greek government’s decision to grant legal status to the Bektashi-Alevis entails changes of disproportionately greater significance.

This is a group of only 3,500–4,000 people who live in a few small villages near Soufli, at the northwestern edge of the Greek border. The consequences of the new regulation for the Bektashis concern, first and foremost, the already sensitive religious human geography of Thrace, but are also expected to have broader and multifaceted effects on Greek-Turkish relations.

For although they are a minority within the Muslim minority, the Bektashi-Alevis represent a particularly relaxed and tolerant approach to the worship of Allah—an approach more akin to Western perceptions of religious devotion than to the traditional, rigid, and draconian Muslim strictness.

At its extreme, that strictness leads to Islamist fanaticism and intolerance as the foundation of faith. In contrast, according to the Bektashi-Alevi doctrine (Bektashis are considered the intellectuals, Alevis the lay faithful), men and women can perform their religious duties on completely equal terms, without the age-old gender-based discrimination that pervades the Islamic world. The same applies to Ramadan, fasting, the strict prohibition of alcohol or pork, etc. Overall, the gentle worldview of the Bektashi-Alevis is by far more humane than that of the Sunni Muslims. And perhaps precisely because of this, Bektashism has historically faced disdain, defamation, and oppression from mainstream Islam.

The Law

Nonetheless, the regulation that radically changes the current framework is part of a new bill promoted by the Ministry of Education and Religious Affairs and passed on August 1. As the Minister, Sofia Zacharaki, pointed out, “this is the first time that a religious legal entity of the Muslim faith is recognized in Greece. In this way, Greece takes another step in the right direction of protecting religious freedom.”

The changes introduced to Greek legislation regarding the Bektashis of Thrace are included in Chapter H of the bill and are detailed in 13 articles. These cover a wide range of issues: recognition of the specific minority community as a religious legal entity, designation of worship sites, management and registration of waqfs (religious property), sources of income and any incompatibilities, religious education in their specific doctrine, matters of religious teachers, etc.

The major point, however, is that respect for the beliefs of the Bektashi-Alevis is institutionalized and gains legal protection—something that inherently strengthens their presence within Greek society. This is particularly important, as the Bektashis never recognized the authority of the muftis of Thrace (who are, of course, appointed by the Greek Ministry of Education), a stance dictated by their religious views but which inevitably placed them at odds with the dominant Muslim element of the broader minority.

As a result, Article 3 of the legislative regulation now stipulates: “The members of the religious community of Bektashi-Alevi Muslims of Thrace, as members of the Muslim minority of Thrace, retain the rights provided under the minority protection provisions of the Treaty of Lausanne as well as under Greek legislation. The article regarding the jurisdiction, responsibilities, and duties of the muftis of Thrace does not apply to them.”

The Turkish Narrative

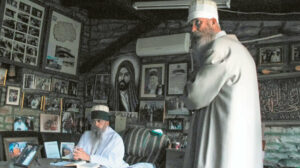

As expected, representatives of the Greek Bektashi community are celebrating the new legal regulation, as they now theoretically, at least in relation to the Greek state, gain equality with the Muslim minority. They cease to be marginalized and subjected to prejudice by Sunni Muslims. And most importantly for them, the Bektashis will henceforth be able to worship freely and in the manner they choose, no longer forced to gather for prayer in disguised, illegal “tekkes,” as their ritual sites are known.

Looking at reactions as a guide to the Greek state’s actions regarding the legal recognition of the Bektashi-Alevis, an interesting starting point is the Turkish media. For example, the newspaper Aydinlik, the official organ of Turkey’s Patriotic Party, titled its report on the Greek government’s bill: “Greece presses the button! The plan to detach the Bektashi-Alevis from the Turkish minority.” In the article, journalist Meral Akaya openly accuses the Greek side of intending to divide the minority Muslim community of Thrace. As she writes, “the controversial legal regulation aims to sow discord within the minority on the basis of faith, undermining the unity and solidarity of the Turks in Western Thrace. This process has been underway for some time, with the denial of the Turkish identity and the division of the Muslim minority into three ethnic groups (Turks, Pomaks, and Roma). Now comes a new division—this time based on religious differences.”

After summarizing the reform introduced by the new Ministry of Education law, Aydinlik gives the floor to Ozan Ahmetoglu, former president of the Turkish Union of Xanthi (TEX), whose activity—like that of Ahmetoglu himself—often aligns with Turkey’s official and unofficial assertive policies.

In an extensive excerpt of his statements as featured in the newspaper, Ahmetoglu claims, among other things, that “Greece is trying to divide a community of our Turkish compatriots numbering 150,000 residents of Western Thrace. But we say there is only one minority in this area: the Turks of Western Thrace. Something the Greek state refuses to accept. Now we have our Bektashi-Alevi brothers, along with their relatives living in the mountainous regions of Evros and Rhodope. All these people are Turks and have lived there for centuries. And here comes the Greek Ministry of Education and Religious Affairs, which wants to designate these compatriots of ours as a distinct legal entity, with a separate legal status. It exempts them from the jurisdiction of the muftis of Western Thrace. This action is not ‘recognition,’ but a deliberate implementation of a divisive policy.”

“The Turkish minority of Western Thrace is against this division because the minority is united. Its rights are defined by the Treaty of Lausanne and the agreements signed between Turkey and Greece. That’s why the Greeks will achieve nothing with their efforts to sow discord among us.” Ahmetoglu further notes, “For the past 30–40 years, Greece has viewed the Turkish element as a threat. But the Turks of Western Thrace have never threatened Greece. There has never been danger from them—on the contrary, the Turks of Western Thrace are a resource for the region. Nevertheless, Greece continues to ignore even the rulings of the European Court of Human Rights by implementing anti-minority policies.”

Brothers or Victims?

Similar positions to those of Aydinlik are expressed by many major Turkish media outlets, clearly revealing that the government of Recep Tayyip Erdoğan is unsettled by the new law regarding the Bektashi-Alevis of Thrace. And certainly not so much because of the doctrinal issues it raises but for geopolitical reasons. In this new ideological-political context, the Turkish side focuses on the unity of the Muslim minority in Thrace, which—besides its appropriation and portrayal as uniformly Turkish—is also presented as monolithic. This is rather a creative interpretation of reality, given that the Bektashis and Sunni Muslims in the region coexist at best within a framework of mutual tolerance.

Until this legislative resolution is translated into daily practice, the Bektashis of Thrace were “Muslims of a lesser god.”

However, the legalization of Cem Evi—the temples of the Alevi doctrine—and their equivalence with the mosques of the dominant Sunni stream among Muslims in Greece, represents a historic and foundational step for this minority community. Precisely because it overturns entrenched (im)balances and brings immediate change to the real lives of thousands in the Thracian region around Roussa and Mikros Dervenos, and overall in about 10 villages.

Whether the social ecosystem of Muslims in Thrace will gradually become a field of friction—ranging from simple discomfort to suspicion and hostility, mostly from Sunnis toward Bektashis—remains to be seen. Traditionally, especially in Turkey, where their community counts about 20 million followers (out of 84.5 million), Bektashis face contempt and hostility from the vastly larger Sunni majority. Obviously, when Ahmetoglu calls them “brothers,” he forgets that in their motherland, Turkey, they have even suffered bloody persecution—with the most notable incident being the massacre of hundreds of Kurdish Bektashis in 1978 by frenzied “Grey Wolves.”

A 700-Year History

Their legal recognition in Greece is a major victory for Bektashi-Alevis outside of Turkey. It’s worth noting that nearly a year ago, in September 2024, the Albanian government announced that it would gladly host an “autonomous Bektashi state” within its borders. Thus, for reasons related either to religious tolerance or to less clear political motives, the Bektashi-Alevis have suddenly found themselves in the spotlight.

From their perspective, a fight for the survival of the “liberal and progressive” version of Islam is finally being vindicated. And specifically in Thrace, especially in Roussa—a sacred place for Bektashism—since there, around the mid-14th century AD, Seyyid Ali Sultan founded the first tekke, or sacred temple, creating a center for religious gathering for Bektashis.

The Bektashis originated in the 13th century in western Anatolia, following the preaching of the mystic sage Haji Bektash Veli. Those who did not remain in Turkey dispersed into pockets across the Balkans—and certainly into Thrace.

Ask me anything

Explore related questions