They say the best mafia stories can’t be told, and perhaps that’s true, but some of them still excite us.

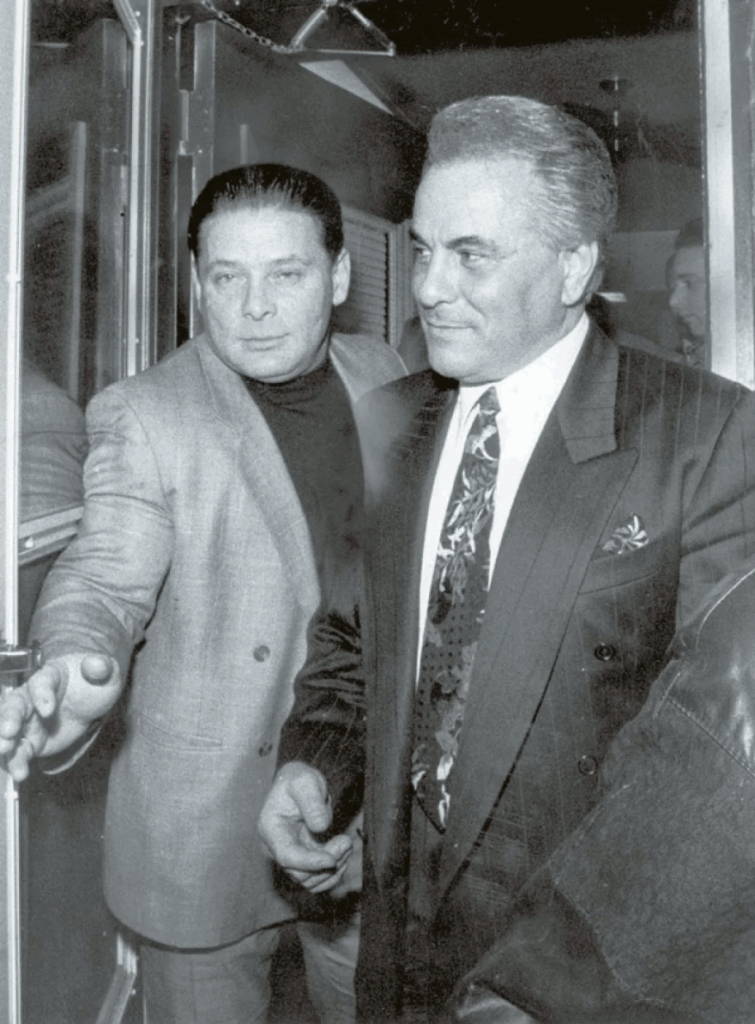

In the late 1970s, notorious John Gotti—who later became the “boss of bosses” of the American Mafia—and Spyros Velentzas often hung out together and were friends.

Although Gotti worked for the Gambino family and the Greek godfather for the Lucchese family, their relationship was harmonious. In one of their meetings, Gotti reportedly told Velentzas: “I never lie because I fear no one. You only lie when you’re afraid.” “Sakaflias” listened and probably smiled, mainly because he himself feared no one during his peak days when he ran New York’s Greek mafia with specific territories.

And it was this activity—usury, extortion, illegal gambling, and a murder he never admitted—that led to his imprisonment in 1990, from which he never emerged, as he refused to cooperate with the FBI and police by giving names and addresses to reduce his sentence.

He “died” at age 90, holding on to the code of silence, and unlike the times when his photo was on newspaper front pages, his death went largely unnoticed in a mafia blog. The cause wasn’t specified, but when you’re 90 and have spent 35 years in a harsh prison, your health is not the best.

Nights at Allenwood

The Allenwood penitentiary, near Lewisburg, Pennsylvania, is a maximum-security prison for hardened, violent offenders. Velentzas certainly belonged to this category, being the most powerful Greek mafia boss in New York, active from the mid-1950s until the early 1990s.

His influence, even without explicit mention, reached the big screen. In a notable scene from the movie “Gotti,” depicting the life of the last major mafia “boss,” John Gotti (played by John Travolta) walks relatively young through Queens with two “associates.”

When asked what they would do to young wannabe gangsters going daily to Astoria and asking for protection money from stores and small businesses, the immediate answer was: “Don’t do anything. The Greeks will handle them,” said with conviction, because he knew that “Greeks,” especially someone who knew very well, didn’t take threats lightly. That someone was none other than Velentzas himself, Gotti’s friend since their teenage years, growing up around Queens and Astoria, until they found their way into the mafia.

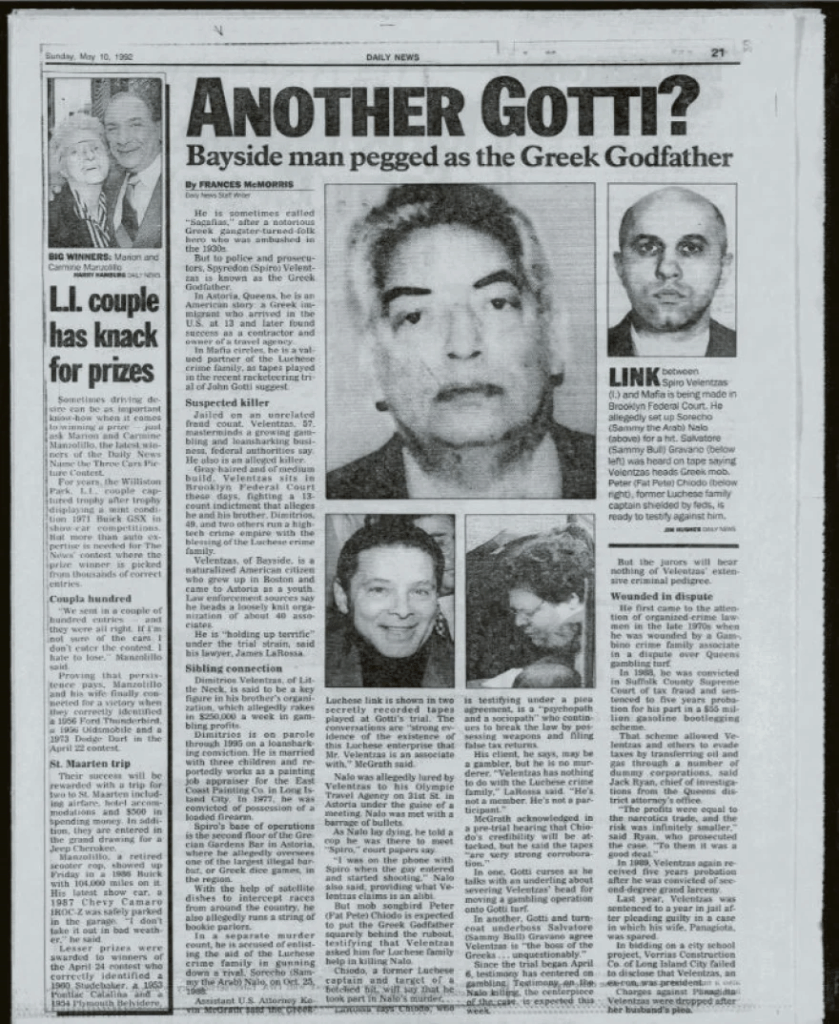

A deeper look into the life of the notorious “Sakaflias” would require consulting American tabloid archives like the Daily News, to learn from old reports about his life and career. Both stories resemble gangster sagas like Martin Scorsese’s “Goodfellas,” featuring mafiosos who grew up together, built enterprises, valued friendship, and sometimes lived on the edge.

The “Greek Godfather” of New York

“Money is always welcome, even when it comes in black bags,” was reportedly one of Velentzas’s favorite sayings. He was a 14-year-old when he first saw Boston—the city where he grew up with his brother Demetris and his sisters. Raised in a family that provided the best they could, his father later sold a restaurant he owned, and in 1950, the family moved to New York.

In Astoria, they found a home, and Velentzas, who wasn’t fond of school, quickly opened a café supported by Peter Kourakos, the “don” of Greek mafiosos.

At the café, gambling—barboudi and poker—was everywhere. When Velentzas served as Kourakos’s driver, taking him to meetings with mafia bosses, his brother Jimmy watched the shop. A significant aspect of this operation was the $10,000 monthly protection fee Velentzas paid to the Lucchese family, one of the most powerful mafia families in the U.S., ensuring punctual payments.

When he first shook hands with John Gotti, then a young “soldier” of the Gambino family, Velentzas was around thirty and deputy leader of Kourakos’s crew. The future “capo di tutti i capi” liked the Greek immigrant instantly, even though he worked for the Gambinos. When Kourakos died, Velentzas was authorized by the Lucchese family to take over the Greek mafia, proving highly capable.

Gotti would often visit Velentzas’s café, playing cards, and he began expanding his operations both in Astoria and Queens. He set up illegal clubs, lent money at high interest rates to gamblers, opened a travel agency, an Italian restaurant, and a bakery selling bagels, fresh bread, and sweets. Money flowed freely, and the Greek “boss” now had time to gamble for hours at the racetrack or dine on fresh pasta in “Little Italy.”

He was seen in the Bronx or Brooklyn with Gotti, Sammy Gravano, and Pitti Chiodo, a Lucchese family member, to whom Velentzas reported directly—unaware that years later, this man would become his nemesis.

Threats

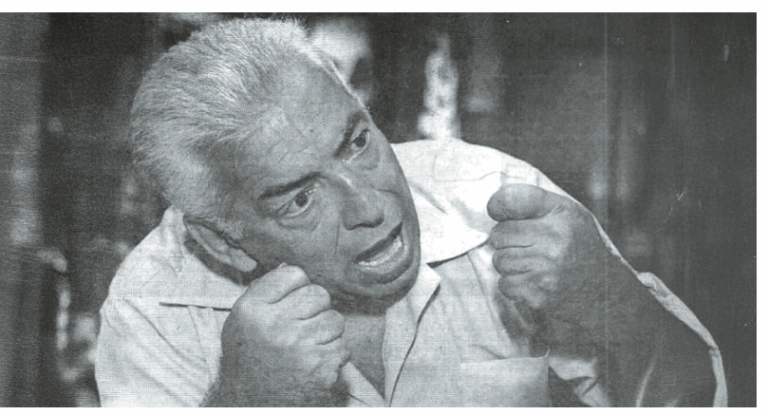

In the early 1980s, Velentzas, the Greek “boss” of Astoria, was raising alarms among smaller mafiosos, mostly Italians. He felt it most acutely one night when he was attacked while returning home, where his wife, Panayiota, awaited him—the woman he loved and married.

He was lightly wounded in the ambush but fought back, exchanging gunfire, and from then on, he became very cautious during outings.

A few days later, he learned that the order for the attack had come from the Gambino family, seeking control of a card club in Queens that Velentzas had taken over. He underestimated the power of a very strong family.

The extent of his influence among mafia circles was revealed in a recorded phone conversation between Gotti and Gambino capo Sammy Gravano, intercepted by the FBI in the mid-1980s.

“I know Velentzas well,” Gotti said. “He’s the boss of the Greeks,” Gravano replied with a single word: “Undoubtedly.” Yet, despite knowing him well and being friends, Gotti—who had already eliminated Paul Castellano and was the “boss of bosses”—became furious when Velentzas encroached on his territory.

How did this happen? Under Chiodo’s guidance, Velentzas opened a Barboudi and other gambling clubs just meters from Gotti’s own baccarat club.

Unbeknownst to him, by representing the Lucchese family, to whom he owed allegiance, Velentzas entered an area controlled solely by the Gambino family.

Ask me anything

Explore related questions