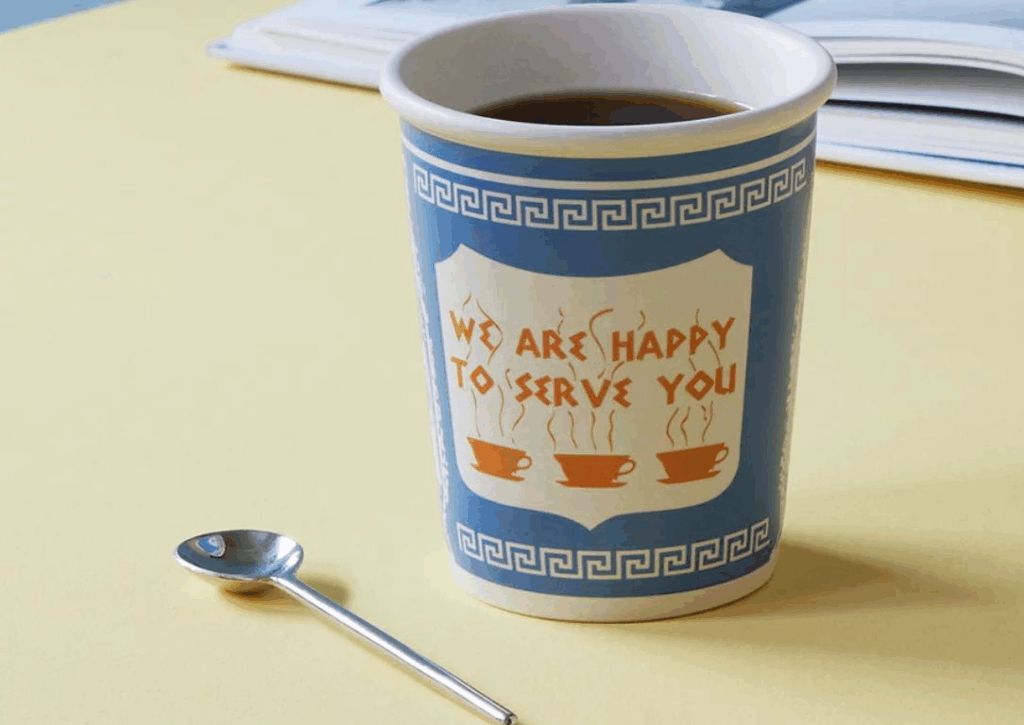

The cheap little paper cup known as the Anthora—designed in 1963 specifically for the restaurants and cafés run by Greek immigrants in New York—was described by The New York Times in 1995 as “the most successful cup in history.” Alongside the yellow taxis and the Empire State Building, the small blue cup has become one of the city’s most recognizable symbols—even though its story begins with a Czech immigrant, Leslie Buck, who drew inspiration from New York’s Greek diners in the 1960s. The cup has appeared in TV shows, films, photoshoots, and posters, becoming an inseparable part of the city’s visual identity.

With elements from Greek tradition

Amphorae, meanders, and the slogan “We Are Happy To Serve You,” printed inside a white frame reminiscent of ancient papyrus. It was a deliberate move by the Sherri Cup company of Connecticut, which in 1963 set out to boost its sales in New York and realized that Greek restaurant and café owners were the key clientele who could make that happen. Buck—who was in marketing, not design—was tasked with creating a cup that would speak directly to them.

His personal story gave him a unique perspective: born as Laszlo Büch in Czechoslovakia, a survivor of concentration camps and later an immigrant to the United States, he had an instinctive understanding of the audience he was trying to reach. And although he had no formal design training, it was enough for him to produce an everyday, almost humble object that would eventually acquire iconic status.

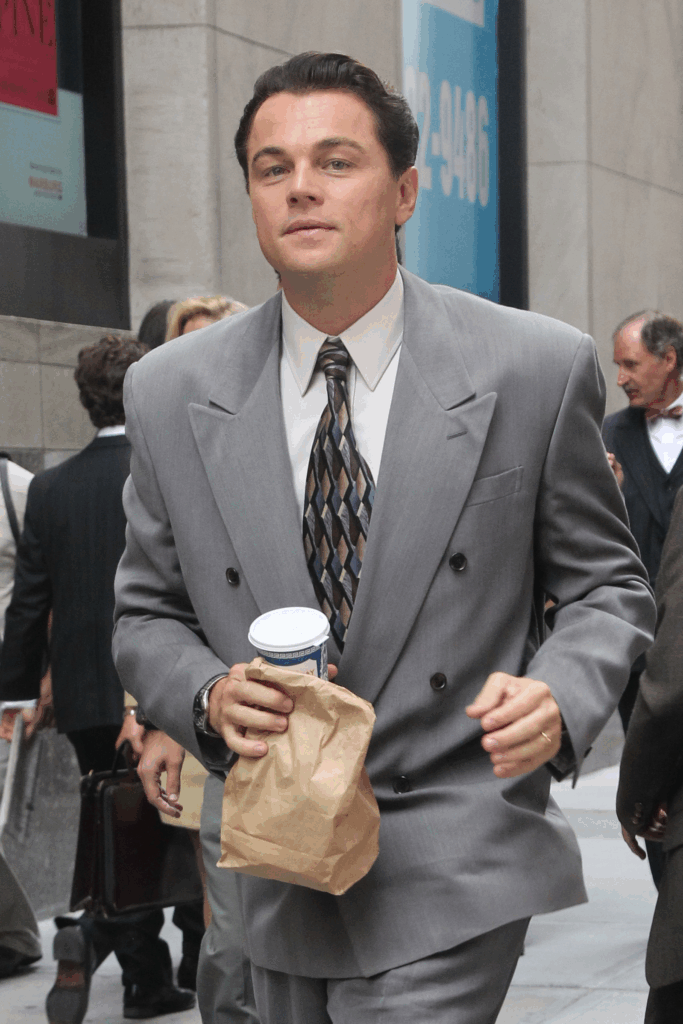

Since the early 20th century, thousands of Greek immigrants had arrived in New York, many of whom opened small restaurants, cafés, and lunch counters—known as Greek diners—where coffee was served almost nonstop and became part of the city’s fuel. Workers, cab drivers, stockbrokers—everyone stopped in briefly for a cup. But until the early 1960s, paper cups remained anonymous and unremarkable: plain white, with no sense of identity. This was the moment the Sherri Cup Company stepped in. Wanting to strengthen its presence in New York, the company recognized Greek diner owners as a crucial customer base and assigned its marketing manager, Leslie Buck, to design a cup that would appeal directly to them.

The name Anthora is often attributed to Leslie Buck’s Eastern European accent, as he is said to have pronounced amphora as anthora. This almost “imaginary” word stuck to the product and has followed it ever since. The cup—with its Greek blue-and-white motifs and its warm message of service—was immediately embraced by Greek shop owners.

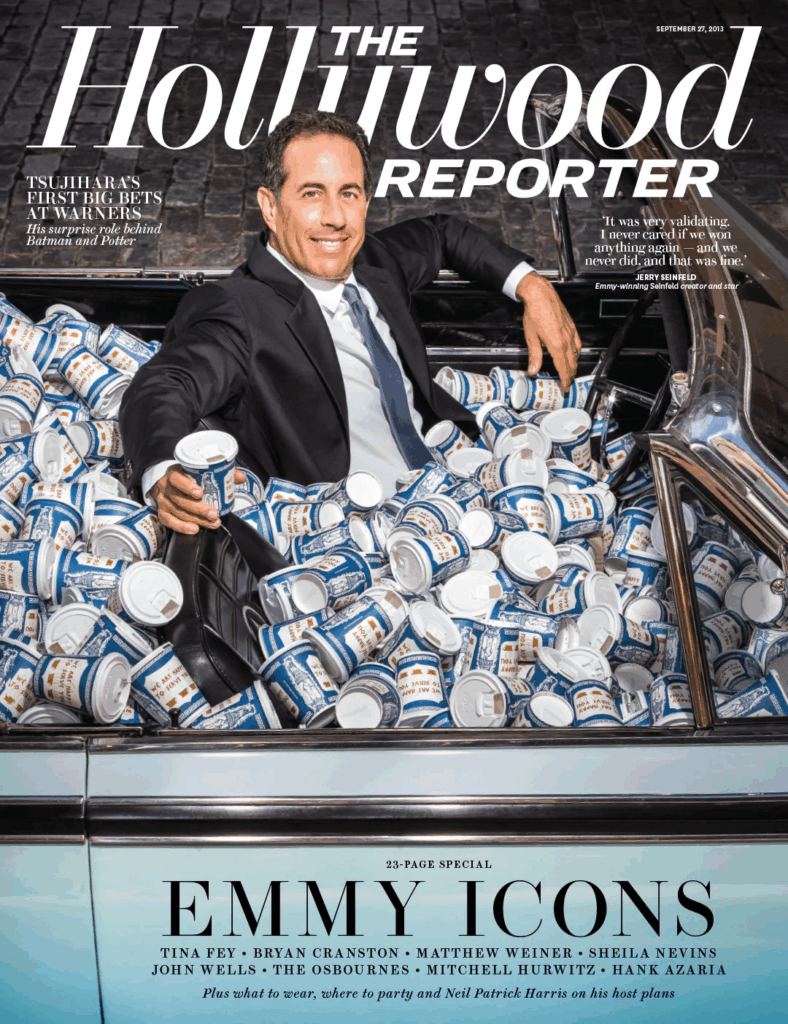

Within just a few years, its use spread across the streets of New York, from the late 1960s through the height of the 1990s—most notably in 1994, when sales reached 500 million dollars. You could see it in everyone’s hands, from construction workers and students to office executives—a democratic image that distilled the city’s everyday life.

As New York’s image spread around the world through film and television, the Anthora became a visual shorthand for the city itself: a single frame was enough to signal the location. But as coffee habits changed and new chains introduced cups with modern logos, the little blue cup began to disappear. In 2006, its production stopped under Solo Cup, the successor to Sherri Cup, though the design continued to be licensed. Its withdrawal from daily use only amplified its mythology, turning it into an almost “endangered object” that evokes nostalgia for a different New York. Companies like NY Coffee Cup eventually brought it back to the market—this time not only for professional use, but also for tourists, collectors, and design enthusiasts.

Leslie Buck never became rich from the cup; he received only symbolic bonuses from its sales, but his name remained in history. When he died in 2010, international media bid farewell to him as “the man behind New York’s cup.” The most fascinating part of the Anthora’s story is that it began as a marketing tool for a very specific industry and ended up becoming a globally recognized symbol of New York.

Its revival today is no coincidence: since 2015 it has been back in production and now comes in larger sizes as well. In fact, it is now also available in a more environmentally friendly version—produced in ceramic form—so it can be used again and again. In Athens, you can currently find it only at the well-known café-bar Chelsea Hotel in Pangrati, which has recently reopened its doors.

Ask me anything

Explore related questions