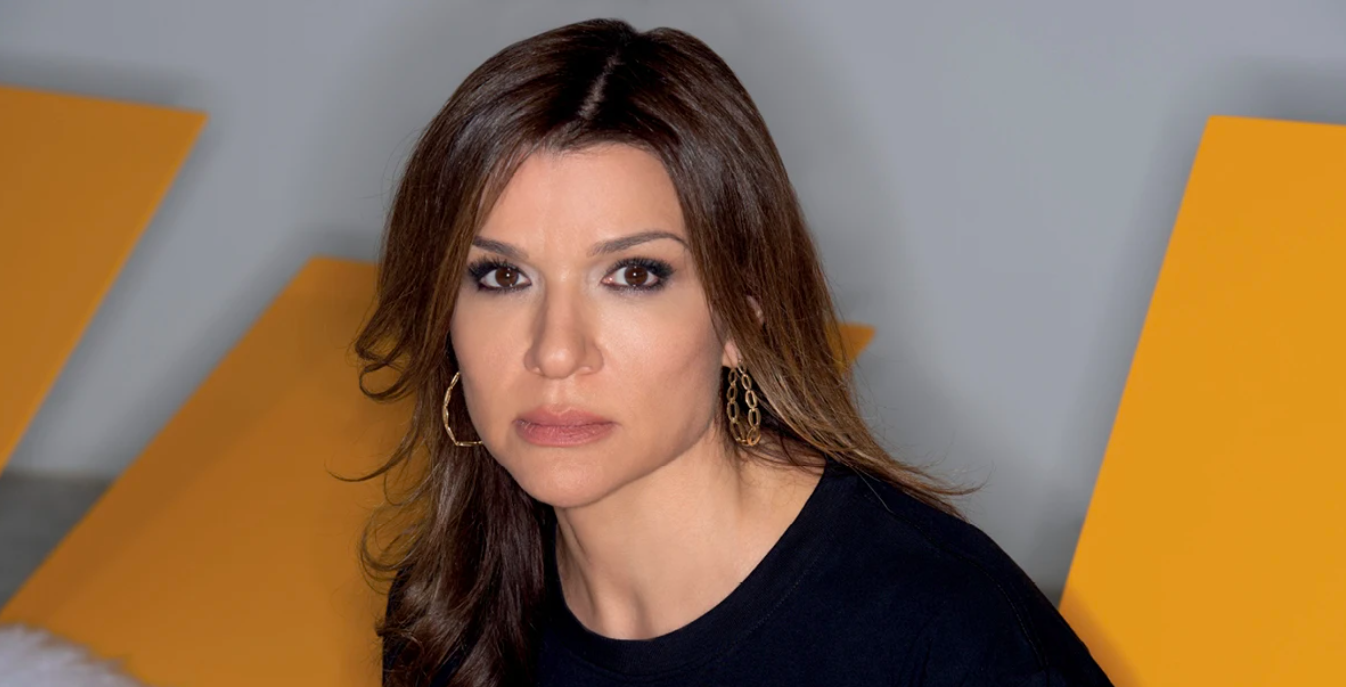

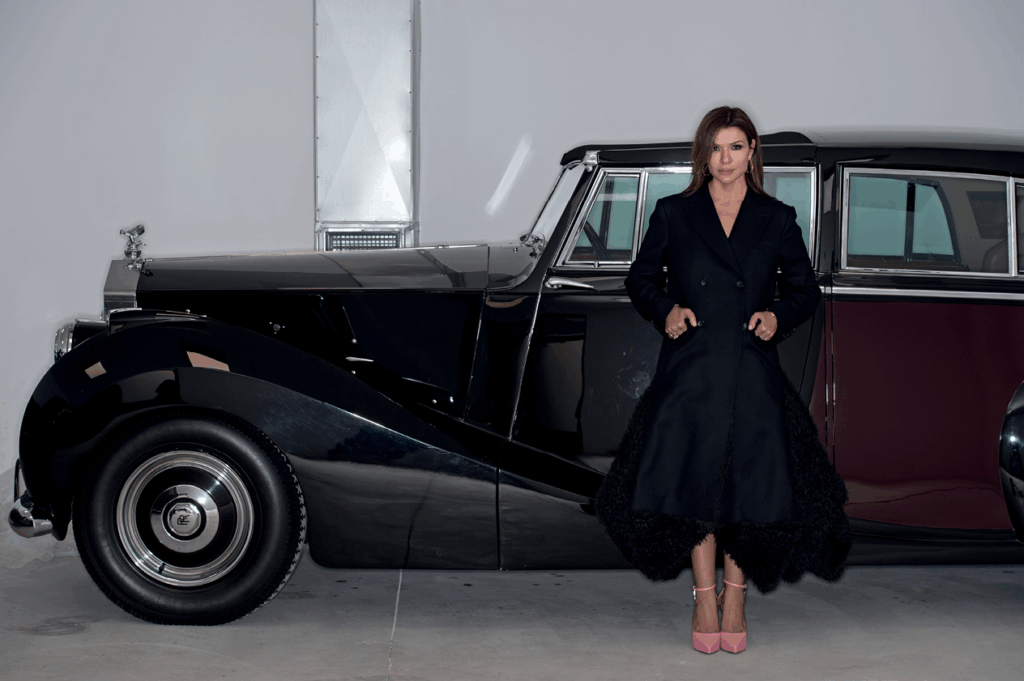

Afroditi Panagiotakou, Artistic Director of the Onassis Cultural Centre and now a member of the Onassis Foundation’s Board of Directors, celebrates 15 years of the artistic organization that transformed Greece’s cultural landscape. She speaks about the magic of community, the love, and the challenges of a full journey from Ioannina to New York.

“I want the ‘together’.” This phrase sums up our conversation—a conversation shared across two places and times: a relaxed sunset at her home and a busy morning at her office. A sea of artworks by Greek and international artists adorn walls, desks, and every surface across the floors that house the Onassis Cultural Centre’s offices on Galaxia Street—a fitting name, as Afroditi says, “Galaxy is the limit.” We open a bottle of mezcal and begin.

I came here to talk about the 15 years of the Onassis Cultural Centre. But first, do you want to tell me about your 15-year-old self? What do you remember of that girl, what do you still hold on to?

I think I still have a creative restlessness. I grew up in a household where laziness was the biggest sin—you weren’t allowed to even sleep in a little longer. I was trained to produce; I never learned what a beautiful thing “chilling out” is. However, as the years go by, I now recommend laziness; I sing the praises of inactivity. It might be an illusion that moving constantly keeps you young. But I believe that pausing is the beginning of creation. Reflection needs calm. And it needs company—the analysis of life. Still, I remain a workaholic until further notice. At 15, apart from having a family that told me never to rest on my laurels, what shaped me most was the need to leave, to explore the world. I couldn’t wait to travel and see how other people live. The thrill of adventure is, for me, the most captivating thing. This thirst defined me then and still defines me now.

Similarly, what shaped the Onassis Cultural Centre 15 years ago when it was born?

Curiosity, energy, boldness. Not to get bored or be boring. To create surprises and beautiful moments of delight. To stand by artists and support them with all our strength. Above all else. To speak internationally about contemporary Greek culture. To build bridges with the rest of the world. I am incredibly lucky—and fought for this—to be able to choose my collaborators. That’s the privilege of leadership: selecting the people you coexist with, live alongside, share space with. In my office, as you can see, there’s only a couch—no desk or chair behind it. So we can sit around, analyze, laugh, disagree, eat, drink—and work. Because we all work hard. I want the “together.” I know, putting the “I” before the “together” sounds a bit paradoxical, but that’s my desire.

A few years ago, the Onassis Cultural Centre introduced one of the most beautiful slogans: “Love makes the family.”

Our engagement with human rights is part of who we are. Love makes the family. Without love, it’s not family; it’s something else. The Onassis Cultural Centre isn’t just a cultural organization. It never was. It’s a living organism, a mindset that aims to inspire a humanitarian and humane way of seeing things. If I had to describe it, I’d say it’s a catalyst: it triggers chemical reactions, accelerates progress. The Onassis Cultural Centre is a community. A community of people who might disagree on whether a performance is good or not, but share a common value system. And for me, values are serious business—they even shape our aesthetics.

The fact that right now we don’t need to introduce ourselves—that organizations and artists out there want to collaborate with us—is, for me, very significant on a national level.

It’s unfair, but if you had to pick moments from these fifteen years, which would you choose?

The most beautiful and profound marks happen behind the scenes—they are more personal moments. They’re connected to the hours of planning, rehearsals, the endless messages between us. Long messages at odd hours. That’s basically my professional autobiography. We’re not a cultural organization focused on productions; we’re here for the artists. It all starts with the process: “Give us the process, and take our soul.” We give time, space, and funding to the creator so they can do what they want—and we stand by them. Dimadis, Tzathas, Kapralou (the dramaturgs and curators at Stegi)… these people are at rehearsals. They don’t wait to see the show at the premiere. For us, the process is more important than the product. The product will come and go; the process continues, takes you somewhere new each time, and builds relationships that give birth to new works. Moments I remember: The Creatures, The Birds, The Clean City, Little Red Riding Hood, Euripidis Laskaridis’ Elenit, the dance performances by Christos Papadopoulos and Dimitris Papaioannou (see, I speak a lot about Greeks because with them we experience the process most intensely), Mario Banushi, the Fast Forward Festival, when I saw The Kiss by Ilias Papaelias in Avdi Square…

Have there been shows or works you knew you were taking a risk on the moment you chose them?

Constantly. That’s what we live for. Safety is a great comfort—and a big trap. Do you know what a gift adrenaline is in your work? Huge. And in the end, what if a show doesn’t turn out as it should? As we’d like? That will happen too. Not often. But it will. Money and time will have been spent. But for us, art is not an investment aimed at profit. Risk becomes responsibility when you say you want to invest in talent, intelligence, imagination. Despite hard work, the desired result might not come. Believe me, though, it’s not the end of the world. And I say this also as an audience member who has seen things I didn’t like. It’s okay. It’s not the end of the world. That’s what we tell artists: better to risk and fail than to play it safe and never grow, never shake the soul a little.

What decision filled you with fear?

Fear? None. Anxiety? Yes. The first time I took on production, with The Birds. I said: I believe we need to do this, and we need to do it this way. I was afraid because it was the first time I was responsible. I really wanted to make a production that was open to many, with a very high standard. I said, since we’re talking about democracy and high aesthetics, let’s also speak emotionally. Because I really love emotion. Now, talking about that show, I see the balloon from The Birds at Epidaurus in my mind. And in New York. And in Chile. It more than confirmed me.

When was the moment you said, “Something’s happening here; Stegi is starting to bring new, louder, more groundbreaking things”?

When I saw I’m Not Afraid on Stegi’s facade. That’s when I said: here we’re doing more than art and culture, we’re making an intervention. It’s about everything. It’s Pavlos Fyssas, but also all the things we need to care about and fight for. If you ask me what I want Stegi’s audience, artists, and staff to shout, I’d say this phrase: “I’m not afraid.” Not “I won’t cry”—I’ll cry a lot. But I won’t be afraid.

I love being the glue between people; I’m crazy about connecting people with each other.

What are you most proud of as an artistic director?

The first thing I’m proud of is my team. The second is the opportunity we’ve given artists to do what they want. And, of course, our audience. On another level, there’s a political aspect: we were the underdog at first on the international stage. It doesn’t matter if you’re Onassis or Stegi—internationally, you’re “Greece,” “The Greeks.” The fact that right now we don’t need to introduce ourselves, that organizations and artists want to collaborate with us, is very important nationally.

Should I add to the important things that Trump “hates” you?

It’s about values. We cannot coexist on the same side of history. Of course, I’ll talk to people who voted for him (not to change their minds—many are set in their ways), but to say a few things, to shake some certainties. We have a strong presence in America. And there was the dilemma: “What do we do now?” Especially since we just moved. After 50 years, we left the Olympic Tower and are now in Soho. Where we should be: in a normal neighborhood, with wonderful offices, great space, alongside artists’ studios, next to bars, in the Village. One floor of offices and one floor where we can show projects—brick walls, outside stairs—like we learned New York from the movies. Escape stairs. Precious.

Escape from what?

From wherever you are—and especially from where you think you’re safe or actually are safe. You must always have an escape route. At restaurants, I sit with my back to the wall and want to see the exit. To see who comes in, have my back covered, and if needed, know where I can leave. Samurai, you get it (referring to the Jean-Pierre Melville movie with Alain Delon). For me, escape relates to freedom. And above freedom, nothing: freedom to be, to love, to not be, to choose.

What criteria do you use to choose collaborators? What do you give the green light to?

What we like—that’s always the criterion, within the framework of freedom and responsibility. When it comes to the Greek taxpayer, education, health, the Onassis Foundation does what it must, follows what the state and society require. But at Stegi, we have the right and duty to take risks, the right to do what we like and what we believe is worth presenting, worth saying. Does it sound selfish? I don’t know. But it’s not.

The first thing I’m proud of is my team. The second is the opportunities we’ve given artists to do what they want. And, of course, our audience.

Has something ever been staged at Stegi that you didn’t like?

Something has come that I didn’t like, but Dimitris Theodoropoulos (Executive Director), the key person for the whole organization and for me, did like it. Or Prodromos Tsiavos (Head of Digital). I’m not the type to say, “I don’t like it, cut it.” I say, “I don’t like it, but if you believe in it…” And no, it’s not a concession; I understand it has its place. After 15 years, of course we can find such examples. There are also things I liked that the team didn’t. I operate with something that’s not exactly instinct—it’s something “beyond instinct.” And my team (I call them “kids” affectionately) recognize this: that I sense something before it even appears. I have this artistically—I’m not talking about human relationships; there I’m a mess: to love someone and then find them rotten, or think they’re rotten and discover they’re amazing. But artistically, I see it before the creator even realizes it. I love being the glue between people; I’m crazy about connecting people. That’s why the tables at my house are the way they are: no one knows who the other will be, no one knows their neighbor. My house is always open. People come, eat, and leave with containers. That’s my family. I take joy in finding the words someone needs to hear to come closer to themselves, to do what they can—even if they don’t know it yet.

Where do you think that comes from? How did you learn not to be afraid?

I took this from my home. In my parental home, we never valued people for their money or power. Never. We preferred those whom others considered outcasts, eccentric, or quirky. I didn’t grow up in a home where “successful” meant someone who drove an expensive car. So, when you grow up somewhere where a person’s value isn’t defined by so-called “objective” success — financial or social — all people seem approachable. Do you like someone? You like them. No? — No. But I think I’ve also learned to be fearless thanks to the Foundation. Because, coming from that home, the easiest thing would have been to think of as “fantastic” only those who are disadvantaged, undermined, or leftist, and as “enemies” those who have money, family, and a name. Now, I include in my life people I consider wonderful. We can’t put everyone under the umbrella of stereotypes. I no longer think that someone is wonderful just because they listen to the same music as me. And I believe the Foundation helped me a lot to come into contact with a wide variety of people and to break stereotypes. Stereotypes exist anyway — I’m not saying it’s good they exist. They do, and, frankly, they come from somewhere. But we can’t bow down to them.

The effort a woman has to make to reach such a position is many times greater than that of a man.

What is the relationship between the Onassis Foundation and the Stegi? Is it like the “child” that sees it grow? Does it see it as autonomous?

Stegi is a teenager. The Foundation, as a parent, wants its child to be autonomous, strong, bright, fearless. And it is there for the tough moments. When we took on this job — and I come back to the values and insist on the way we took it — we sent our CVs. I remember the original team, the people we worked very hard with. I especially highlight Christos Karras and Katia Arfaras. When we first came, we thought we were probably from another world. We thought we’d be called to respond to something conservative. We were quickly and spectacularly proven wrong. But it was purely a decision of the president: Antonis Papadimitriou decided to trust people who would do something different. And I believe we did.

Tell me about what you heard as a “captain at the helm” because you were a woman — things a man wouldn’t hear.

It’s not just a trend to talk about the position of women in society. We live it constantly. And I don’t like to complain or say “as a woman, I suffered.” No. But the effort a woman has to make to reach such a position is many times greater than that of a man. Does society still care about gender? Absolutely yes. But having teenage daughters (Yasmin and Isabella, whose priority in my life is non-negotiable), I will stress it a hundred thousand times: it all has to do with how we raise our sons. If we want change, we have to think about how we raise our sons.

How do we put a brake on the culture of patriarchy?

In cooperation with men. Together. Raising children differently, trying to inform those around us. You see political choices around the world — a dangerous arc of conservatism growing, talk of abortion bans. For this, I will blame my generation and those who vote, who elect leaders with deeply dangerous conservative views. This society that speaks against abortion, for a “new” moral system where only whites fit and “the immigrant is bad” — fortunately, this is not Greece. But we must remember that what happens out there comes here. We have work to resist. That’s why for me, a tremendously important word right now is Europe. We have serious work to do as cultural organizations in Europe. Europe, with all its problems and aging, I think is awakening right now. The fact that Paris is blooming and London is fading means something.

Why do you pick those two cities?

Because Paris, as a serious European city, stands and says: “We are here to bring together different people, to accept them, to give them space to act, to create, to move in public space, to converse with strangers.” London, after Brexit, ceased to be what it was: it became inhospitable, scared, fearful of foreigners. And when you become inhospitable to the stranger, you cease to be a city. Because a city is a place where you meet strangers and converse with those who carry stories different from your own.

Ask me anything

Explore related questions