They say that art brings people together. In reality, however, because art – and especially the visual arts – is embedded in an informal stock market of values, it sometimes ignites passions, hatreds and quarrels, for which in the end justice is called upon to provide a solution.

And this is because when we are talking about works by renowned painters – sculptors, which in many cases are valued at small or even large fortunes, ownership and inheritance rights easily turn into a long-term battlefield with an indefinite end. One such dispute, which has been unfolding in recent years away from the limelight, is now coming to light and concerns a family whose late patriarch, Stavros Psicharis, was for many years a reference point not only in the press and politics, but also in society at large, which follows with interest the powerful of the land.

Three years after Stavros Psicharis’ death, the dispute of the domestic civil war concerns the claim of 19 paintings of well-known Greek and foreign painters by his son from his first marriage Andreas Psicharis from his second wife ,Christina Tsoutsoura.

A case that until a few years ago would have seemed unthinkable for the Greek media is now unfolding on the stage of the political courts. Andreas Psicharis, a former New Democracy MP and son of the late publisher of the Lambrakis News Agency (DOL), is taking his father’s widow Christina Tsoutsouras to court. The subject of his lawsuit is the paintings of great value that the major publisher owned and hosted in his house: these are 19 works of high artistic and financial value by very large and famous artists, such as Picasso, Delacroix, Dali, Munch, Lytras, etc., which, as he claims in his lawsuit, he acquired exclusively himself and gave them to his father for safekeeping during his years of service abroad.

The picture of open conflict shows that the collapse of DOL in 2017 and the death of Stavros Psicharis five years later not only dragged down the historic publishing edifice, but also the unity of the family that ran it.

In the wake of that financial and moral disintegration, personal and property claims are now emerging, definitively demystifying a dynasty that once dominated public life.

In his lawsuit, Andreas Psycharis describes in detail his life abroad from 1995 to 2003, when he served as a diplomatic official in London, Nicosia and Washington, D.C.

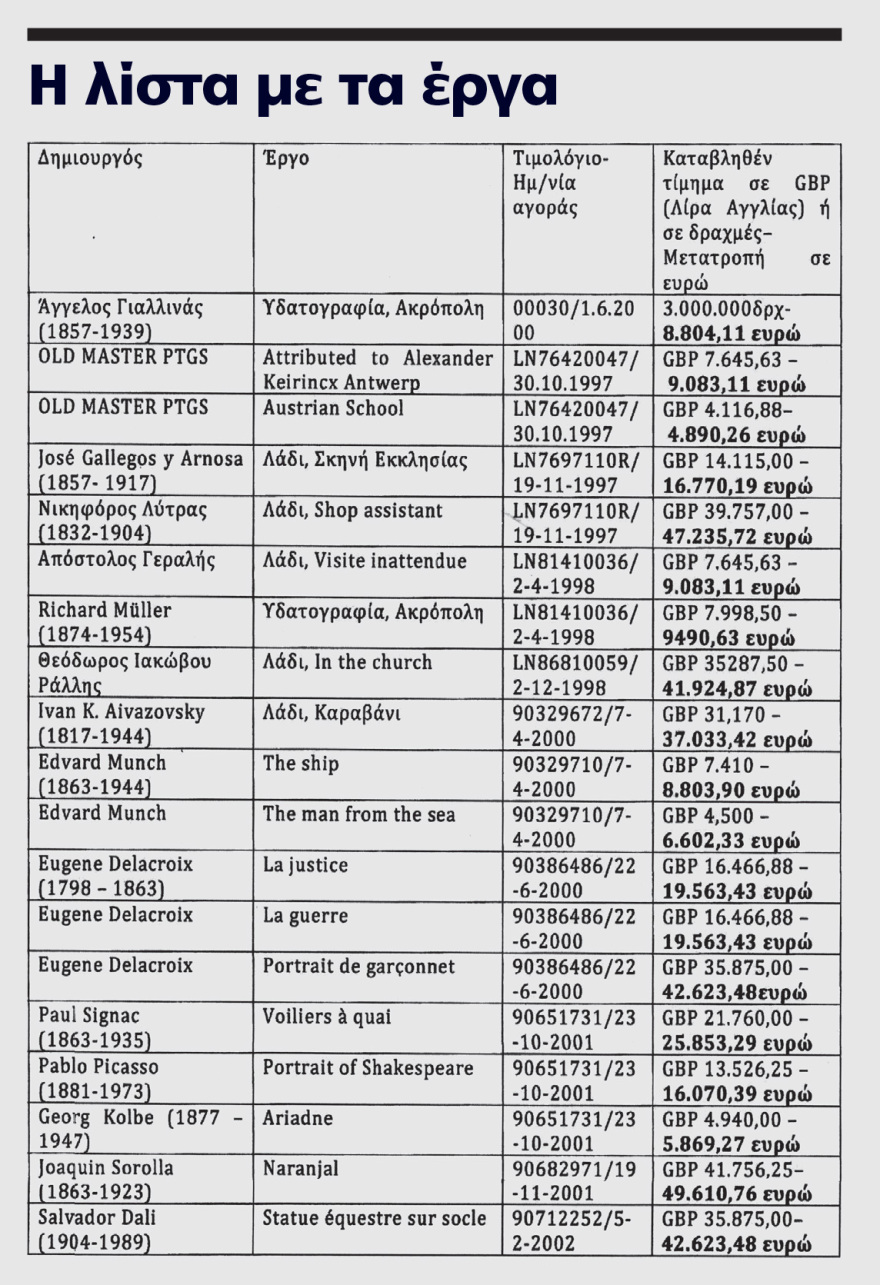

During that period, as he claims in his lawsuit (at a time when there was no requirement to file an “alibi” and no proof of the origin of money was required), he was buying artworks of personal interest from Sotheby’s and Christie’s as the highest bidder. His reference to these international houses further indicates the authenticity of the works and the certificates accompanying each purchase.

“Due to my constant absence abroad and the value of the works, which necessitated their safe custody, I gave the works to my father Stavros Psicharis, who resided with his defendant wife and my half-sisters in a privately owned residence/maisonette at 30 Lycabettos Street in Kolonaki, for safekeeping, having the necessary security measures, as well as a guard in his capacity as the publisher of the historical newspapers “Vima” and “Nea”,” his son Andreas said in his lawsuit.

This is the luxurious residence with an unobstructed view of the Acropolis and Lycabettus, which the late publisher felt proud of and proudly showed off to the executives of DOL and his political friends when he invited them to the well-known election receptions. It was a residence for a display of power and strength, with dozens of works of art adorning its walls and the host in the role of guide talking about the paintings, their style, their history and the general work of artists such as Pablo Picasso, Salvador Dali, Eugene Delacroix, Edvard Munch and Nikephoros Lytras. Works that would be the envy of the greatest collectors, but also of wealthy Greeks, whose authenticity and artistic value cannot be questioned, as his scientific friend at the time was the well-known collector and art appraiser Panagiotis Kouvoutsakis, who had also served as a management consultant.

However, his son claims that with purchase invoices in his name, only 19 paintings out of the dozens his father displayed.

But the reader of the list of works is puzzled by the purchase prices listed, as the works of these artists cost hundreds of thousands of euros.

According to Andreas Psicharis’ claims and based on the documents available to him, he spent 346,312.40 pounds and an additional 8,804.11 euros, bringing the total amount to 421,499.18 euros. However, according to estimates by people in the art market, the actual value of the 19 works in his collection is currently estimated at several times that amount. Suffice it to mention that in the art market, it is estimated that even a small work by Picasso, Dali, Munch, or Delacroix is valued at 2 million euros or more.

The same circles also point out that the amount of money shown as the initial acquisition cost in no way reflects their commercial value, especially since these are paintings attributed to world-renowned artists, who rarely appear on the market today for less than six-figure prices. However, it is worth looking at the development of this civil war through the lawsuit filed by Andreas Psicharis against his father’s widow, Christina Tsoutsouras.

“In the autumn of 2017 I acquired my first privately owned residence at 34 Lycabettus Street and since then I have lived there as a family. I requested my works from my father, who of course told me to pick them up whenever I wanted. The defendant, having been informed of the imminent receipt of my works and taking advantage of the poor physical and psychological condition of my father and her husband, told me that the paintings are hers, refusing since then any contact and communication with me”.

“Weighing my father’s health,” Andreas Psicharis continues in his lawsuit, “and the unbearable distress that the dispute with the defendant would cause him, I did not rush to receive the paintings and avoided legal actions that necessarily involve performance, curators, etc. Besides, my father’s health was deteriorating as he was suffering from Parkinson’s disease, while he gradually lost all his movable and immovable property (except my works, of course, as he did not own them) from 2018 until very recently to repay loan obligations that he had guaranteed individually”.

He then refers to his father’s move to Porto Rafti after being evicted from his residence in Kolonaki, which was sold by the lending bank Alpha Bank without an auction. During that period and until the death of the major publisher (2/8/2022), the plaintiff claims that he had no contact with his father, as he was guarded by the defendant and did not communicate with him.

On 7/2020/2020, a last ditch effort is made through a proxy attorney to peacefully resolve the dispute and a letter is sent to Christina Tsoutsoura’s attorney, which, among other things, states: “Andreas brought to my attention the catalogue of works that he had purchased 20 years ago at Sotheby’s auctions and had handed over to his father for safekeeping. I understand that due to his father’s state of health, his wife Christina refuses to hand them over to Andreas, which has caused serious friction between them since 2017. Christina’s refusal is incomprehensible while even his father’s diligent creditors have recognized the collection as Andrew’s property. For the sole purpose of avoiding legal action in this regard, Andreas would be willing to notarially donate certain works from his collection to his half-sisters at his absolute discretion.”

However, this attempt also fell on deaf ears as to date, Christina Tsoutsoura reportedly claims that these works were purchased with money spent by her late husband, and therefore belong to her. This position is at the core of the dispute, as Andreas Psicharis insists in his lawsuit that the works were acquired solely with his own funds during his time working abroad and he never transferred the rights or possession of them.

The collection that became the apple of the eye

If one looks for the cause of the tension, one will find it in Andreas Psicharis’ own choices. The collection consists not of decorative works, but of names that figure in international auctions and museums. According to the documents of the lawsuit, the beginning was made with the work of high technical and historical importance, a watercolor “Acropolis” by Angelos Yialinas, worth 8,804 euros. This was followed by two works by the Old Master School, one attributed to Alexander Kairinx, purchased at the 1997 auctions at a price of EUR 8,804, and the second, by the Austrian school, at a value of EUR 4,890. The collection was enriched by the impressive 19th-century oil painting “Church Scene” by José Galliagos i Arnosa, acquired for 23,293 euros, and “Shop assistant” by Nikiforos Lytras, a work typical of the Greek school of ethnography.

Next comes the painting “Visite inattendue” by Apostolos Geralis, priced at 13,870 euros, followed by one of the most special works in the collection: an oil by Richard Miller, bought for 27,033 euros, with the dramatic and insightful detail that characterised the German painter.

On the list of claimed works is “In the church” by the Greek-Egyptian painter Theodoros Rallis, acquired for 41,924 euros. It is followed by “Caravan” by Ivan Aivazovsky, one of the world’s leading marine painters, for 37,033 euros. From the 2000 auctions come two paintings by Edvard Munch (“The ship” and “The man from the sea”), acquired for €8 890 and €5 327 respectively. Works with a strong psychographic dimension, associated with the most mature phase of the leading Norwegian artist, in which the iconic work with worldwide appeal and recognition, “Scream”, belongs.

Eugene Delacroix’s three works constitute a separate chapter: “La Justice”, “La guerre” and “Portrait de garçonnet”. Andreas Psicharis, according to his claims, acquired them all at the same auction in 2000, the first two for 19,563 euros each and the third for 10,525 euros.

“The Portrait of the Painter”.

In the final phase of the collection’s creation, in 2001-2002, we find Paul Siniak (“Voiliers à quai”, around 28,000 euros), Pablo Picasso (“Portrait of Shakespeare”, 16,070 euros), Georg Kolbe (“Ariadne”) and, finally, Salvador Dali with “Statue équestre sur socle”, bought for 42,623 euros. The case, which already outlines an unprecedented family rupture, takes on even more impressive dimensions as it is revealed in the pages of Andreas Psicharis’ lawsuit. With details that have not seen the light of day until now, the controversy surrounding the 19 paintings takes on a heavy emotional and moral footprint.

The lawsuit stresses that other works purchased by his father through auctions in the 1990s-2000s, all with certificates of authenticity, were in the same house. Andreas Psicharis is choosing for now to claim only the 19 works of his own ownership, but reserving the right to come back for the rest in the future.

On 19 December 2024 he sent a new extrajudicial invitation to the widow Psicharis. Again, according to the record, he received no reply. After years of silence, tensions and fruitless attempts at extrajudicial communication, the plaintiff now turns to the courts seeking recognition of his exclusive ownership of the 19 works of art and their immediate return.

The claim

According to the text of the lawsuit, Andreas Psicharis claims that his father’s wife, Christina Tsoutsoura, “illegally neglected and possessed” the works of art, refusing to return them despite repeated requests to do so. The plaintiff urges the court to recognize that the works are his exclusive property and that the defendant must return them.

If the paintings cannot be physically returned, which is implied to be likely, he seeks an award of damages equal to the total purchase value: €421,499.18, the sum resulting from the £346,312.40 paid at auctions between 1997 and 2002, plus the £3 million of the same period, all convertible to the current price. At this point it should be noted that the claimant has reportedly recently been informed that some of the works he claims may have already been sold by the defendant Christina Tsoutsoura.

Another interesting element of the lawsuit is that Andreas Psicharis is also activating the “unjust enrichment” provision in the alternative. Simply put, even if the court does not enter into the substance of ownership, even if it turns out that for whatever reason the works cannot be returned, the defendant, according to the argument of the lawsuit, cannot remain in possession of them, nor benefit from their value.

This is one of the strongest legal supports for this type of case: when a person has in his possession property that does not belong to him, he is obliged to return it or render its value. Thus, the case is closed, at least at the level of a lawsuit, where it would inevitably end up, the courtrooms. On the one hand, a son who states that for years he avoided conflict to protect his father. On the other hand, the widow of the DOL publisher, who, according to the allegations, remains unmoved.

Andreas Psicharis’ lawyer, Marizanna Kikiri, told “THEMA” that her client, after requesting in an extrajudicial notice the delivery of the works of art that demonstrably belong to him and receiving no response from the opposing party, was forced to resort to the courts. He aims to have the paintings, which are his property, returned to him.

Ask me anything

Explore related questions