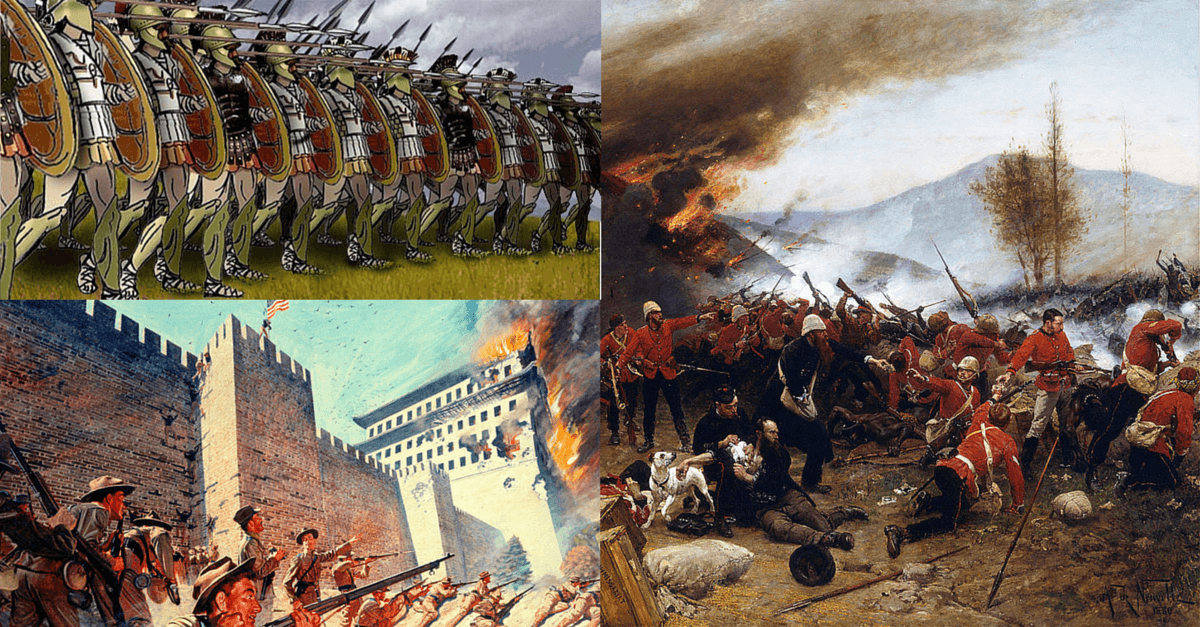

Sometimes men are faced with impossible odds, hopelessly outnumbered or facing a merciless enemy with better weapons or other overwhelming advantages. Occasionally these terrible odds are overcome, as in the battles of Rorke’s Drift and Stalingrad. Other times, such as at the Alamo or Thermopylae, the bravest stood and fought to the bitter end with valiant efforts worthy of remembrance. Here are a few of the most impressively valiant stands throughout history, of course, these are just three examples and there are countless others: Shiroyama, Bastogne, The Warsaw Uprising, Stalingrad, and many more that may be in future articles.

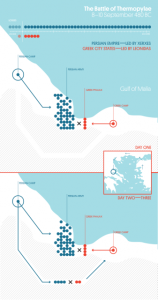

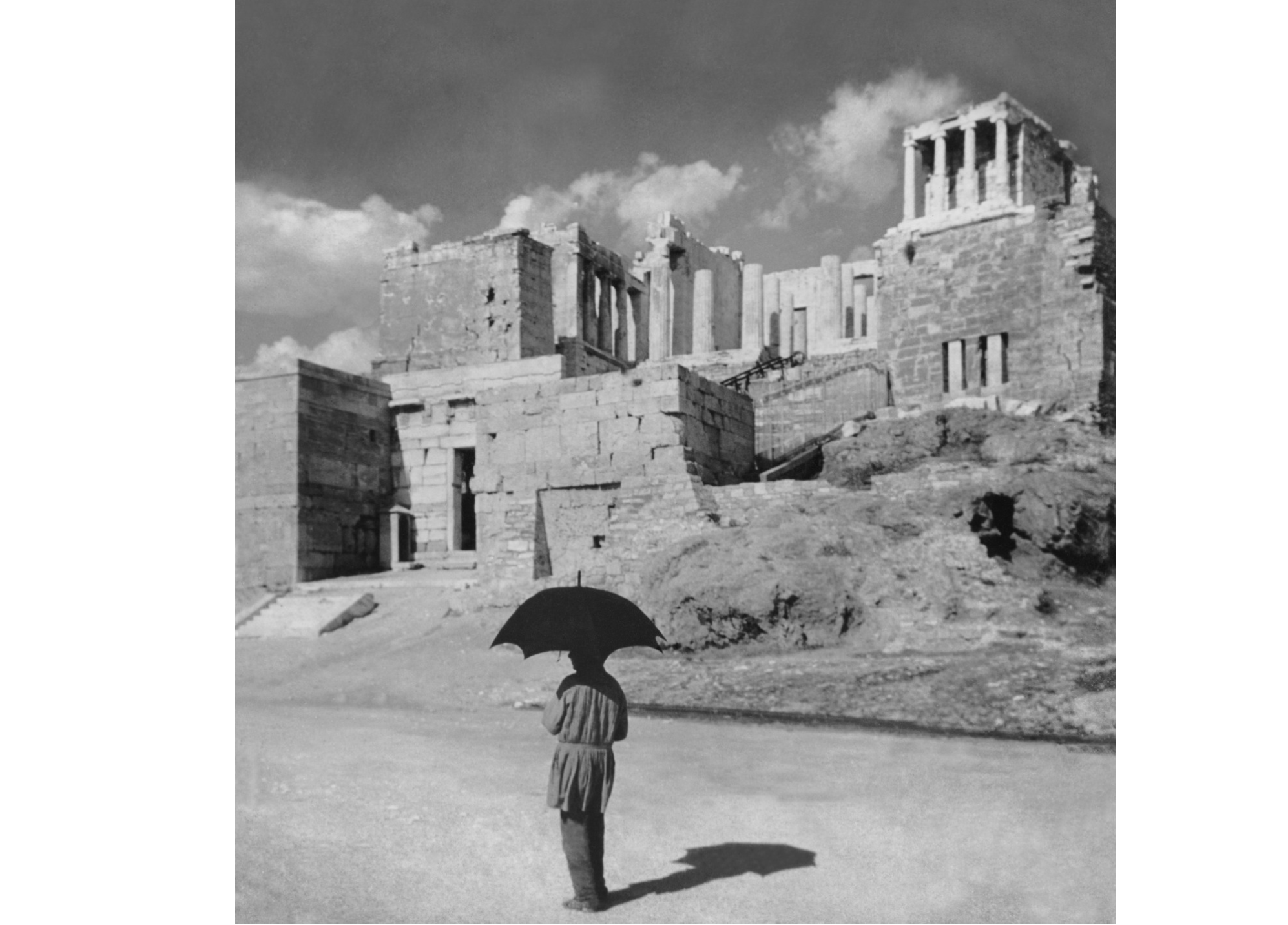

Thermopylae 480 BCE

This has got to be the best example of a valiant stand as ever there was. Some may say that it was blown out of proportion, but it was indeed an epic stand by some of the bravest and most effective warriors of all history.

When Xerxes reached the “hot gates” of Thermopylae he found 300 Spartans, but also approximately 7,000 other Greek hoplites as well as their many slaves. A decent force until you consider that Xerxes had about 150-250,000 men (estimates vary wildly).

The Greek hoplites fought off tens of thousands of Persian troops, but not at the same time, thanks to the narrow passes of Thermopylae. In the bottleneck, the best of the Persians were no match for the best of the Greeks; the 7,000 allies fighting alongside the Spartans were far from pushovers.

(The narrow pass worked wonders for the Greeks, until Xerxes was shown a shortcut)

After several days of Greek victories, Xerxes’ men were led around the Greek position. The Spartans, 400 Thebans, and 700 Thespians choose to stay and fight. This brave force fought with all their might, but had little hope once surrounded and engaged on all sides. Their stand bought the other Greeks time to retreat, but it also fueled the flames of resistance against the Persian invasion. The stand at Thermopylae is remembered throughout the history of war as a testament to the skill and determination of these fearsome warriors.

Rorke’s Drift

Going much further forward in history we come to the mismatched battles involving British colonial troops armed with guns and cavalry against tribal warriors with spears and shields. At the battle of Isandlwana in South Africa, these tribal Zulu troops demolished an organized British army. The Zulu prevailed, despite a very limited use of firearms, largely with extremely aggressive attacks with overwhelming numbers.

So when the small garrison at the supply depot/hospital at Rorke’s Drift, at the border of Zulu and British colonial territory, heard of the defeat from the straggling survivors, they were understandably panicked. They quickly decided that a column of retreating men laden with hospital patients would soon be overtaken by the fresh Zulu reserves (who had not seen fighting at Isandlwana) heading towards their position and resolved to stand and fight.

The space between the supply building and hospital was reinforced with 200-pound bags of grain known as mealie bags, almost as good as sand bags. Being a supply depot, the men had plenty to use. With about 4,000 Zulu bearing down on them, the 150 or so men in the Drift created gun loops to shoot out of and barricaded the doors.

(This painting essentially shows all of the battlefield that was Rorke’s Drift. A compact, desperate defense)

The fight often became hand-to-hand and room-to-room. The British in the hospital had to create a hole through the wall to drag the wounded patients, though some too sick to move were killed in their beds. Attacks continued until after midnight, with random shots fired from the few Zulus with guns well into the night. Through all this the British lost about 17 men, killed or fatally wounded.

The Zulu had already won a great victory at Isandlwana, and had hard-marched without adequate supplies for days, so the next morning they retreated to home territory. The defending British had killed over 350 Zulu warriors, with men stacked high at the walls and piled under the gun loop windows. This was one of the most impressive stands by so few against so many.

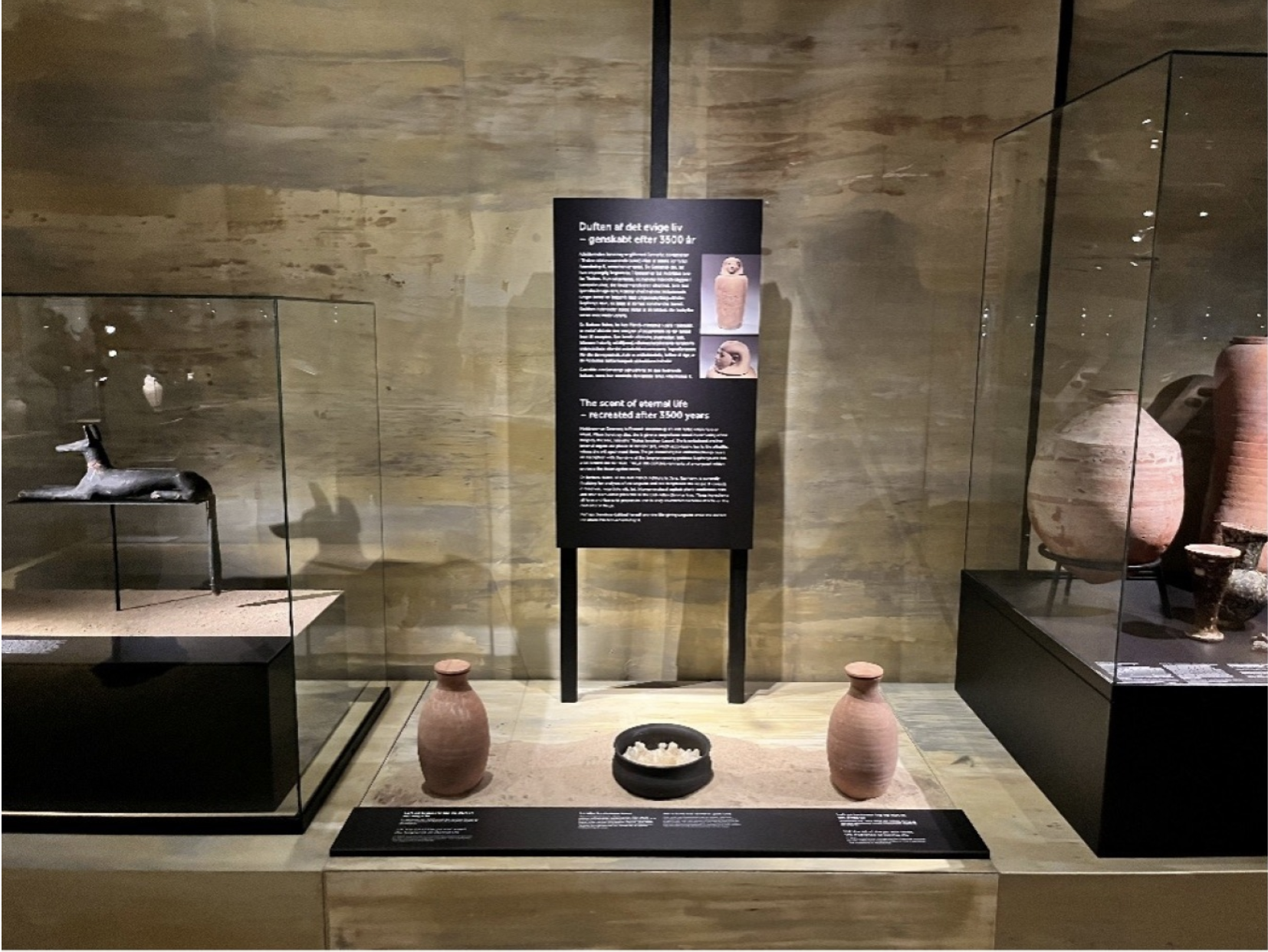

The Siege of the International Legations

It isn’t often that a national government openly sides with a band of murderous rebels, but in the first year of the 20th century, the Qing Dynasty did just that when they sided with the Boxer rebels. The Boxer rebellion was an intensely nationalistic rebellion aimed at eliminating the many advanced foreign powers that bullied their way into China.

When the legations of the various nations heard of the Boxer uprising they barricaded themselves in the compact Legate quarter of Beijing. Due to high tensions, the Legations had a decent compliment of soldiers with the combined strength of the British, American, French, Russian, German, Italian, Japanese, and other nations equaling just over 400 soldiers. A few thousand Chinese Christians also sought protection in the Legation quarter and many civilians pitched in to build defenses or stood a post to fight.

Once the government of China, under the Qing Dynasty, joined the Boxers, they besieged the city with 20,000 men and about an equal amount in reserve. The Legation’s defense was overseen by the British Minister, Claude MacDonald with the American diplomat Herbert Squires as the chief of staff, though each nation took semi-independent charge of their own section’s defense. The Americans had the most weapons and ammo while the Italians had a cannon serviceable with old parts and ammunition found somewhere in the quarter. The cannon would be fondly remembered as “The International” by her multi-national crew.

(The defenders, from Chinese Christians to diplomats and missionaries, took the defense quite seriously, as it seemed that the Boxers would show no mercy if they got into the quarter)

Missionaries took over the tasks such as rationing, hygiene, water and healthcare, while the American missionary Frank Gamewell was appointed to oversee all fortifications, a job he took quite seriously. Frank would receive great recognition for his efforts through the siege.

Throughout the siege the Chinese slowly moved their barricades closer to the Legation’s walls and fighting was a steady grind with a few ceasefires coming down from the indecisive Empress who reluctantly besieged the city to appease the large group of nationalist Boxers. The indecision likely saved the legations as they had lost a third of their forces before the multinational relief army marched to Beijing.

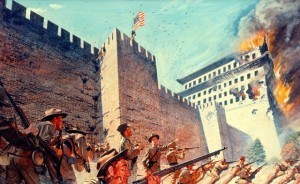

(The American contingent of the relief force scaled the walls to get to the Legations. The British found an unguarded gate and got there faster)

When the besiegers realized that the relief army was close, they redoubled their efforts at taking the quarter but failed to do so before the 20,000-man relief force burst into the city. The British were the first to make it to the Legation quarter and after some heavy fighting, the Chinese retreated with heavy losses. Had the 20,000 Chinese been more organized they could have taken the quarter, but scattered attacks were repeatedly repulsed and the defenders were able to hold out until help arrived. Despite the inefficient siege, the defenders were certainly pushed to their limit, with many prominent leaders killed or wounded and many ordinary men recognized for their duty and heroism.

Ask me anything

Explore related questions