The bucardo was the first animal to be resurrected from the depths of extinction. It was also the first animal to go extinct twice.

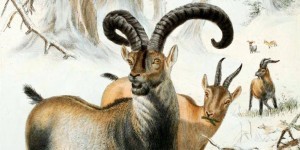

Also known as the Pyrenean ibex, the bucardo was once a common sight in the idyllic Pyrenees mountains that border France and Spain, as well as the Basque Country, Navarre, north Aragon, and north Catalonia. Despite being figures of regional pride, their grand curly horns made them an attractive target for hunters and towards the latter half of the 20th century they were more often seen mounted on the walls of hunting cabins than they were roaming the hillsides.

Extensive breeding efforts took place throughout the 1980s but it was too little too late. By 1997, just one bucardo was left. Rangers found this remaining individual, a 13-year-old female named Celia, mangled beneath a fallen tree in a remote part of Ordesa National Park in January 2000.

The bucardo had joined the ranks of the dodo. But fortunately for this curly-horned creature, all was not lost.

(An illustration of the bucardo from the book ‘Wild oxen, sheep & goats of all lands, living and extinct’ (1898) by Richard Lydekker. From a sketch by Joseph Wolf in the possession of Lady Brooke)

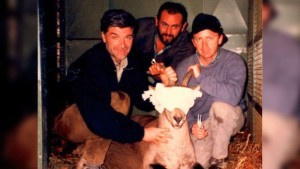

Alberto Fernández-Arias, a wildlife veterinarian who had previously researched the reproduction of the Spanish ibex, captured this female 10 months before her death using a blowpipe, and took cell samples from her ear and flank. These cells were taken back to a lab where they were cultivated and then exposed to deep-freeze cryopreservation.

“Cloning in mammals was thought to be impossible,” Alberto told IFLScience. “Then in 1996, there was Dolly the Sheep. And that changed a lot of things.”

Using Alberto’s expertise in Spanish ibex reproduction, a team of French and Spanish scientists led by Jose Folch began working with these sacred cells left by Celia. You can read the ins and outs of the scientific study in the rather obscure journal Theriogenology. After some delay, it was eventually published in 2009.

The team injected nuclei from the bucardo’s cells into goat eggs that had been emptied of their own genetic material. They then implanted these eggs into hybrids of Spanish ibex and domestic goats. They managed to implant 57 embryos. However, just seven of these hybrids became pregnant and six eventually miscarried. One, however, was a success.

Against all odds, a female bucardo kid was born on July 30, 2003.

“I pulled out the little bucardo. For that moment, it was the first time in history that an extinct animal was brought back alive,” Alberto added.

Alberto managed to explain the miraculous event with a remarkable amount of steely scientific restraint: “We were just like robots about it. We knew everyone had a particular skill, and we were being just professional.”

(Capture of the last Bucardo: From left to right Juan Seijas (biologist), Elías Echegoyen (CITA/Aragón), and Alberto Fernández-Arias, Head of the Hunting, Fishing, and Wetlands Service of Aragón. “Celia” is anesthetized with ears and eyes protected. Ordesa and Monte Perdido National Park)

Humanity had defeated extinction for the first time. Albeit very, very briefly.

“As soon as I had the animal in my hands, I knew it had respiratory distress. We had oxygen and special drugs prepared, but it could not breathe properly. In seven or 10 minutes, it became dead.”

The story did not hit the public’s imagination until 2009 when the scientific study was published. By then, the money had dried up and many of the researchers had parted ways. It seemed the bucardo was to remain extinct once more.

The idea of de-extinction still holds a zealous appeal to scientists and the public alike, as if humanity is striving to attain a God-like mastery of nature and life. The Lazarus Project in Australia has set its sights on resurrecting the Gastric-brooding frog from extinction, a species native to Queensland that has a stomach for a womb and gives birth through its mouth. Remarkably, the scientists working on the project managed to obtain extinct frog cell nuclei from tissue samples collected in the 1970s before its extinction.

This milestone of the bucardo’s (very short) de-extinction might sound a bit like a Jurassic Park-style leap into the future. However, the scientists on the project did not see themselves as glorious pioneers removing the chains of extinction. For them, it was all about the bucardo.

Alberto explained, “When the bucardo were alive, we were trying to save them. When they all died, we were still just trying to save them”.

Source: iflscience.com

Ask me anything

Explore related questions