The Bulgarian nation re-emerged in the 19th century after centuries of obscurity. This resurgence immediately resulted in conflicts with the Greeks in regions where the two peoples had peacefully coexisted.

One of these regions was Eastern Rumelia (Northern Thrace), where, in 1885 and 1906, violent surges of Bulgarian nationalism, along with the implementation of totalitarian methods later adopted by the Ottoman Empire and Nazi Germany, led to the brutal expulsion of Greeks who had lived there since antiquity.

Today’s article focuses on the events of 1885.

Relations Between Greece and Its Northern Neighbors in the 19th and 20th Centuries

Relations between Greece and its northern neighbors in the 19th and 20th centuries underwent many fluctuations, particularly due to the national awakening of the Balkan peoples and the weakening of the Ottoman Empire. The collapse of the empire dangerously intensified the Eastern Question—whether it would be partitioned or remain intact.

This issue involved the Great Powers of the time, especially Great Britain and Russia. Russia, in the 19th century, “discovered” the Bulgarian nation. A similar situation occurred in the 20th century with the creation of a “Macedonian” consciousness among the ethnically unformed Slavic masses in the Skopje region.

The attempt to create a Bulgarian state in the 19th century caused widespread instability in the Balkans and had disastrous consequences for Hellenism, which was completely uprooted from Northern Thrace, now southern Bulgaria.

The Creation of Bulgarian National Consciousness

The conquest of Bulgarian territories by the Ottomans resulted in the near-total disappearance of the Bulgarian nation.

Unlike the Greeks, who revolted repeatedly, the Bulgarians were more passive under Ottoman rule. This passivity was attributed to the settlement of numerous Turkish colonists in Bulgarian territories and, more significantly, to the abolition of the Bulgarian Patriarchate in 1394.

While the abolition benefited the Ecumenical Patriarchate, the Bulgarians lost their spiritual leadership and were unable to preserve their national traditions. Notably, Bulgarian folk songs contain minimal references to their medieval history.

Until the early 19th century, the Bulgarian nation was unknown in Western Europe and Russia. Bulgarians were often mistaken for Greeks, Serbs, or Vlachs.

Efforts to awaken Bulgarian national consciousness began in the 18th century. A Bulgarian monk, Paisios, published a book in Bulgarian using Greek characters in 1762, aiming to foster national identity. However, his efforts achieved little.

Bulgarian national awakening was achieved in the 19th century with Russian support. During the Russo-Turkish wars of 1806–1812 and 1828–1829, some diaspora Bulgarians fought alongside the Russian army.

As the Russians advanced into the Balkans, they discovered an “unknown” people who spoke a language closely related to Russian.

The Crisis of Eastern Rumelia in 1885 and the Beginning of the Destruction of the Hellenism of Northern Thrace

The Bulgarians’ demonstrations of loyalty to Russia, combined with Bulgaria’s geographical proximity to Constantinople—Russia’s “eternal goal” for access to the warm seas—led to the Bulgarians becoming closer allies to the Russians than the Serbs or Greeks, according to Nikolaos G. Nikoloudis.

Russia financed the establishment of Bulgarian schools, and after the mid-19th century, the proclamation of Pan-Slavism, which advocated for the liberation of all Slavs under Russian protection, intensified Bulgarian national awakening efforts.

With Russian instigation, the separation of the Bulgarian Church from the Ecumenical Patriarchate was pursued. This was achieved in 1870 with a Sultan’s decree recognizing the Bulgarian (Exarchate) Church’s jurisdiction over thirteen provinces in Bulgaria.

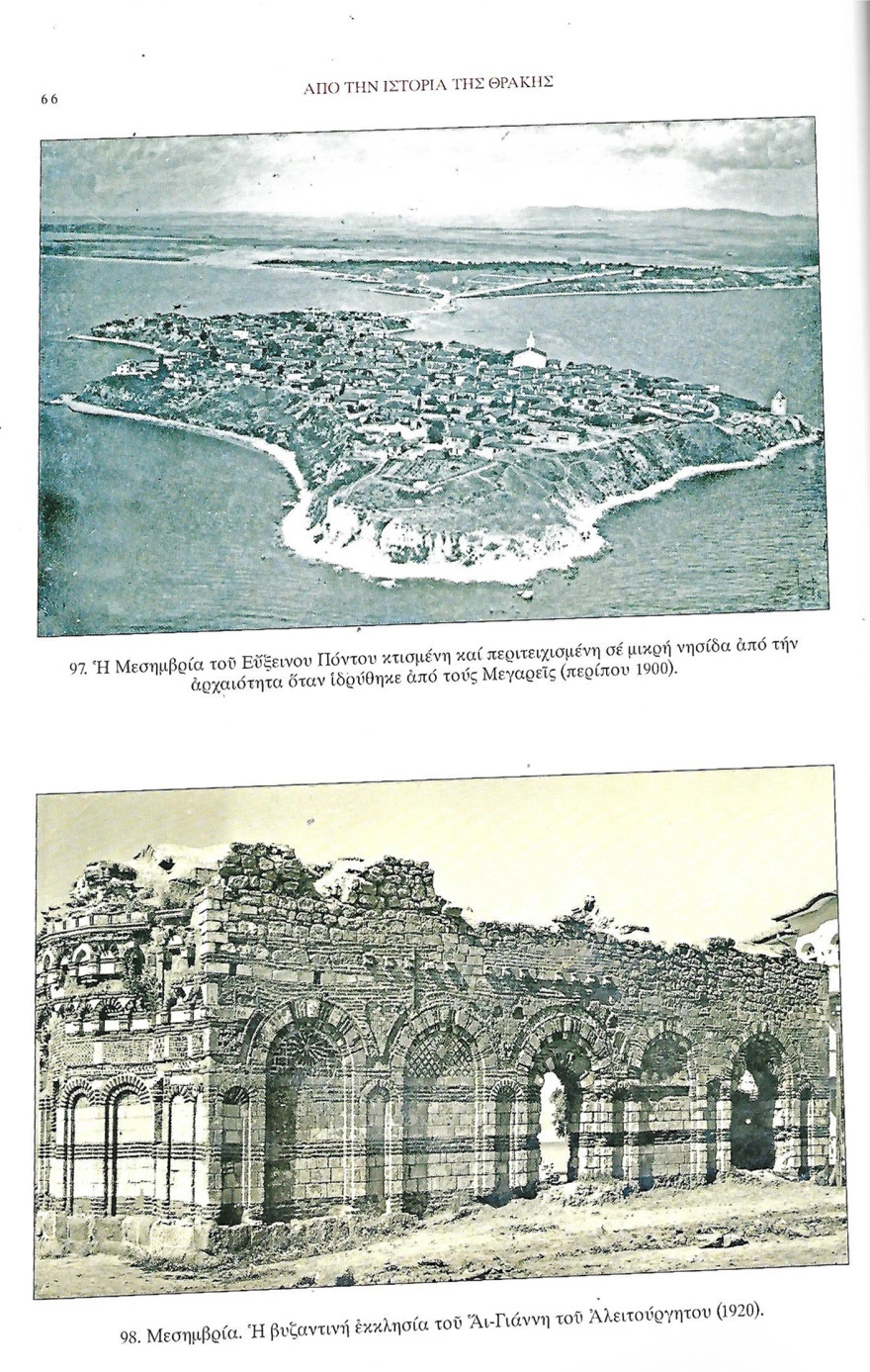

Georgios A. Megas, in his book Eastern Rumelia (Athens, 1945), notes that the Sultan’s decree excluded five metropolitan dioceses (Philippopolis, Varna, Anchialos, Mesembria, and Sozopolis), where the Greek population prevailed.

The Ecumenical Patriarchate reacted by convening a Great Synod in 1872, which condemned the new autocephalous Bulgarian Church and its leaders as schismatic.

The Greek government also reacted, as the Exarchate Church exerted cultural and national influence, particularly in Macedonia. Consequently, Greece supported the Ecumenical Patriarchate, education, and various Greek associations in Macedonia and Thrace.

The Establishment of the Bulgarian State

The establishment of a Bulgarian state soon became feasible, again with Russian support. This effort was initiated by two successive Bulgarian uprisings (September 1875 and May 1876), which the Ottomans easily suppressed. However, the atrocities committed during the second uprising shocked the world: 200 villages were plundered, 80 were burned, and 30,000 people were massacred. In the village of Batak, a center of the rebellion, 5,000 of its 7,000 inhabitants were slaughtered.

Konstantinos Vakalooulos describes the atrocities: “Turkish atrocities occurred throughout the summer of 1876 in Bulgarian areas north of Philippopolis, where entire villages were burned, compulsory levies were imposed on locals, properties were looted, massacres followed the surrender of hidden weapons, and unspeakable scenes unfolded daily.”

The Turkish atrocities provoked reactions that culminated in the Russo-Turkish War of 1877–1878, the defeat of the Turks, and the Russian advance to San Stefano, a suburb of Constantinople, where the Treaty of San Stefano was signed in 1878.

This treaty established “Greater Bulgaria,” with an area of 160,000 square kilometers, encompassing all of Macedonia (except Thessaloniki and Chalkidiki) and Thrace. The European powers, particularly Great Britain and Austria-Hungary, opposed this, resulting in the redrawing of Balkan borders during the Berlin Congress (June 13–July 13, 1878).

In place of “Greater Bulgaria,” two principalities were established as vassals of the Sultan: Bulgaria, with Sofia as its capital, and Eastern Rumelia, with Plovdiv as its capital.

By 1881, the Bulgarian principality, located between the Balkan Mountains and the Danube, covered an area of 24,360 square miles and had a population of 1,998,982. In comparison, Greece, following the annexation of Thessaly and part of Epirus, had an area of 25,041 square miles and a population of 1,235,713, while Serbia had an area of 20,850 square miles and a population of 1,734,316.

Eastern Rumelia (a more accurate term would be “Roumelia,” meaning “land of the Romans” or Christians, due to the Christian majority population) was created on shaky foundations. It covered an area of 35,000 square kilometers (not miles, take note!) and had a population of 750,000, comprising Bulgarians, Greeks, and Turks.

Its governor was to be a Christian, and its Constitution (an Organic Statute with 495 articles and appendices) drafted by European legal experts and approved on May 20, 1880, guaranteed equality of all citizens regardless of religion, equal representation in state administration, equality of the three languages, freedom of education, respect for individual sovereignty, and more.

However, the Austrian representative in the committee of legal experts remarked: “I insist on granting equal rights to the Greek language… The Greeks here possess a far superior and greater intellectual culture compared to the Turks and Bulgarians… It is a fact that the Greeks are not only carriers of civilization but are also capable of transmitting civilization to other nationalities…”

Nevertheless, for the Bulgarians, the establishment of Eastern Rumelia, which resulted from the arbitrary partition of a part of Thrace, was seen as a temporary setback to the vision of “Greater Bulgaria.”

They believed that the region had paid a heavy toll in blood during the uprisings of 1875–1876, while it also had a relative majority of Bulgarian inhabitants.

The Hellenism of Eastern Rumelia

Eastern Rumelia (referred to as Roumelie Orientale during the Berlin Congress) bore the name “Romania” according to lead seals dating back to the 8th century.

The Bulgarians referred to the northern Thracian plain as Romania and its inhabitants as Romantsi. The region’s population was 750,000. Pavlos Karolidis estimated the Greek population at 250,000.

The Ecumenical Patriarchate calculated the total population of Eastern Rumelia at 545,000, of which 234,000 were Bulgarians, 175,000 Turks, 78,000 Greeks, and 58,000 of other ethnicities.

The Greek population in Eastern Rumelia had begun to decline during the early centuries of Ottoman rule. However, starting from the 17th century, following an invitation by the Turks, Greeks from southern regions settled there.

The Greeks of Northern Thrace did not remain passive under Ottoman rule, as evidenced by the presence of local neo-martyrs and klephtic songs. Greek schools in Northern Thrace began to expand after 1595. Many Greeks from the region joined the Filiki Etaireia (Society of Friends), the fourth member of which, after its three founders, was Antonios Komizopoulos from Plovdiv.

Young men from Eastern Rumelia fought in the ranks of the Sacred Band, while in April 1821, the Greeks of Sozopolis raised the flag of the Revolution. However, the movement was crushed, and the Metropolitan and local leaders were executed by hanging.

For most of the 19th century, the Bulgarians were a minority in Eastern Rumelia, according to accounts by foreign travelers. The famous French poet Lamartine, who visited Plovdiv in 1832, did not mention Bulgarians living there but only Greeks, Armenians, and Turks.

The Bulgarian teacher Joachim Gruev admitted that apart from 12 families, which he even named (!), everyone in Plovdiv spoke Greek (M. Apostolidou, “The Bulgarians in Plovdiv under Ottoman Rule,” Thracian Treasure Archive, Volume 10).

The Frenchman Albert Dumont, who traveled through Northern Thrace in 1868, mentions: “… the Greek holds a prominent position here. The Greeks provided the Bulgarians with the little education they have acquired to this day.”

In Eastern Rumelia, apart from the five Greek Metropolises, there were 113 central churches, 100 chapels, 10 monasteries, and 66 Greek schools with 7,943 students. Dumont, in addition to visiting Philippopolis (Plovdiv), also visited Stenimachos.

He writes: “Stenimachos, located a day’s journey from Philippopolis (Felibe), counts 15,000 souls and is exclusively inhabited by Greeks. Neither Turks nor Bulgarians managed to settle there.”

The Bulgarian professor Ischiirkoff admits that the Bulgarians only descended into the plains and formed the first Bulgarian villages in Eastern Rumelia after 1829, when the Turks thinned out due to wars. This view is confirmed by the fact that none of the old place names in Eastern Rumelia are Bulgarian.

All are either Greek or Turkish. This reality was the basis for the British Foreign Minister, the Marquess of Salisbury, who declared at the Congress of Berlin in 1878: “Thrace and Macedonia are as Greek as Crete.”

The looming negative developments in Northern Thrace were foreseen early by the Ecumenical Patriarch Joachim III, who, in a letter dated May 16, 1879, to the British ambassador in Constantinople, Sir Henry Drummond Wolff, emphasized: “Russia has deliberately worked to stoke the flames for its plans. Unfortunately, it seems that the past has failed to open the eyes of those who wish to see the East free from Slavism… If this plan pursued by the Exarch (Bulgarian ‘Patriarch’) and Slavic politics ultimately succeeds, then in ten years, we will witness the full realization of the plan according to the Treaty of San Stefano…”

The words of Joachim III were particularly prophetic. Unfortunately, similar warnings are rarely heeded in Greece, with well-known and disastrous results.

The State Organization of Eastern Rumelia

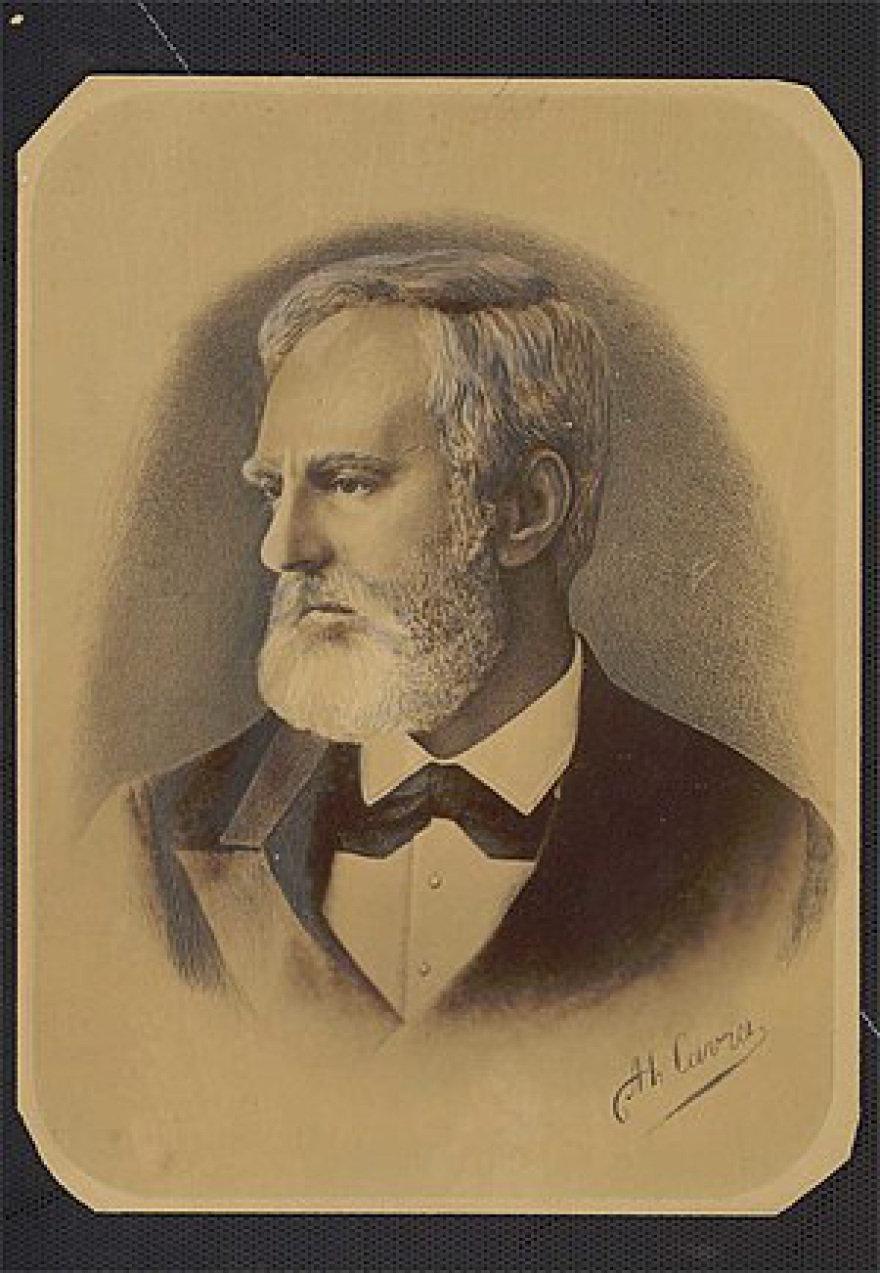

The first governor of Eastern Rumelia was appointed by Sultan Abdul Hamid II as Alexander Vogorides (“Aleko Pasha”), of Bulgarian descent and the son of Stefan Vogorides, the ruler of Samos.

Alexander Vogorides had previously served as the Ottoman Empire’s ambassador to Vienna. He spoke little Bulgarian but was fluent in Greek, Turkish, and French. On May 15/27, 1879, Russian General Stolypin handed over the governance of the principality to Vogorides.

During their administration of Eastern Rumelia, which lasted over a year, the Russians flagrantly favored the Bulgarians. Initially, Vogorides, who was warmly received by all the inhabitants of Eastern Rumelia, attempted to carry out his duties fairly.

However, he gradually began to show favoritism toward the Bulgarians. Many attribute Vogorides’ stance to his associates, particularly Gabriel Krestovitch (later “Gabriel Pasha”), who collaborated with Russian agents. During the same period, the appeals of Greek residents went unheard.

The Greek consul in Philippopolis (1874–1881), Athanasios Matalas, sent reports to the Greek government suggesting measures to safeguard the Greek presence in Northern Thrace (implementation of the Ottoman administrative system, official use of the Greek language), but these were never implemented.

Even the British Blue Book, compiled in 1880 following the recommendations of the Great Powers and containing reports demonstrating the Bulgarization policies in Eastern Rumelia, went unnoticed. Vogorides was removed after his term ended, as he was not sufficiently submissive to the Russians.

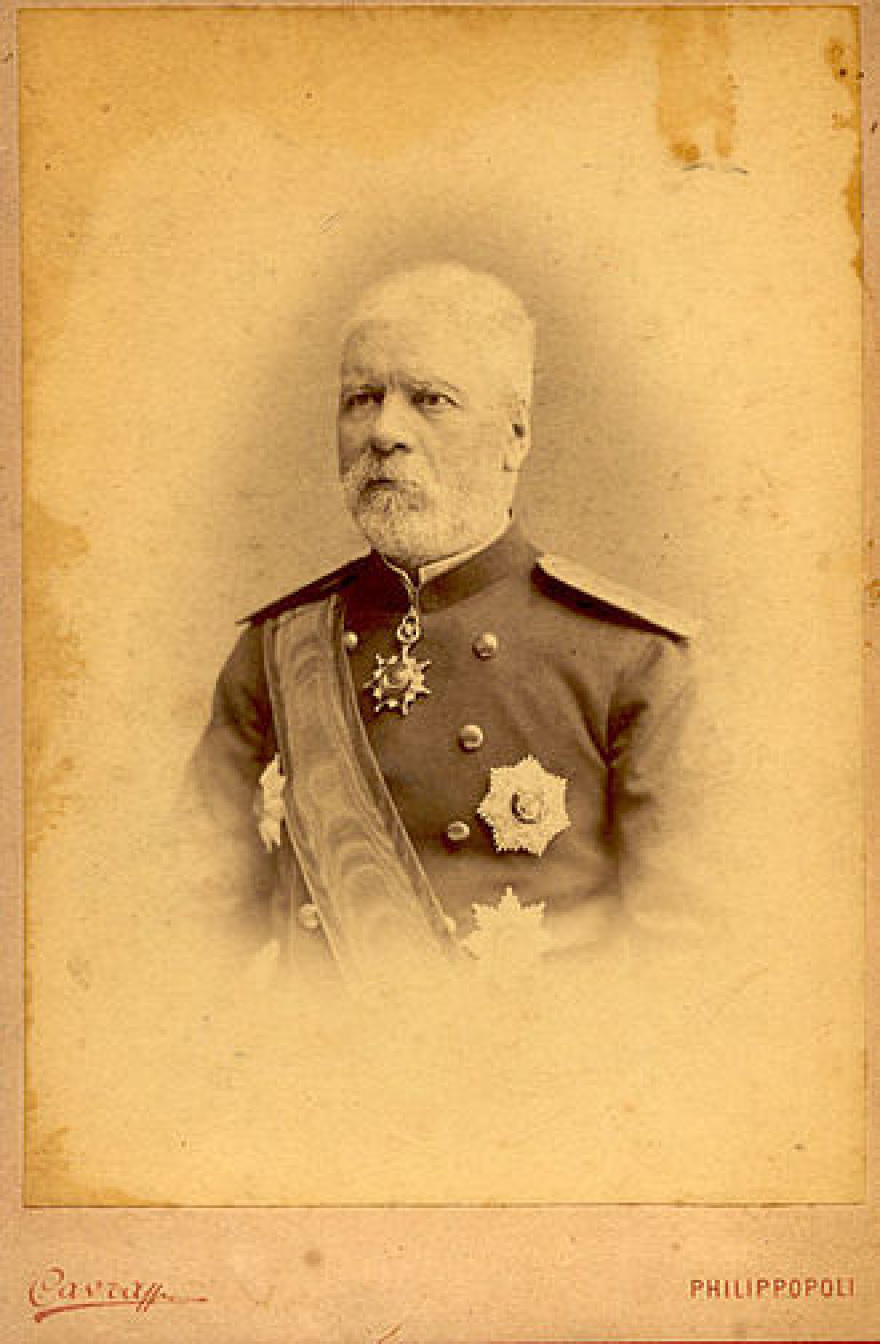

His position was taken over by the pro-Russian Krestovitch, who, according to Hamilton Lang, was “an insignificant simpleton,” “a nobody with a respectable appearance,” “a trivial figure who owed his position to Russian influence,” “a well-dressed puppet.”

The Events of April 1885

In April 1885, serious incidents broke out in Philippopolis (Plovdiv). The Greeks decided to celebrate with great festivity the name day of King George I. A few days earlier, the Bulgarians had pompously celebrated the millennium of the Slavic Apostles Cyril and Methodius, unaware, of course, that these figures were Greeks and, in fact, Thessalonians!

On the eve of the celebration, the Greeks, in coordination with the Greek Consul Dako, decorated their homes with flags. Around 9 p.m., 50 Bulgarians seized the flag from the café on Saat-Tepe Hill, descended to the Dzhumaya Square, and, as more of their compatriots joined in, they stormed Greek homes and looted various items. The police looked on indifferently.

Stubborn as ever, the Greeks re-decorated their homes the next day and attended church services. Despite a police ban, the Bulgarians organized a demonstration and attacked Greek homes. The Greeks resisted. A characteristic example is that of Maria Zotiadou, the wife of a lawyer, who threatened the Bulgarians trying to take down her Greek flag with a revolver.

Following extensive incidents, several people were arrested, but only Greeks were imprisoned! The Greek newspaper Philippopolis wrote in its French edition:

“The organizers of the events of April 23rd believe that a few torn flags, some broken windows, and all the noise made by Bulgarian demonstrators are strong enough to destroy, in one day, in this country, in this city, a Greek presence of 3,300 years.”

The insult to the Greek flag caused a stir in Greece. The government of Theodoros Deligiannis declared mobilization. The only “compensation” given to Greece was a formal ceremony honoring the Greek flag—achieved only after lengthy negotiations! A similar gesture occurred in 1955 after the September Pogrom and the destruction of Hellenism in Constantinople. Turkey “resolved” the matter by hoisting the Greek flag in Smyrna, on October 24, 1955, by Turkish Minister of Transport Muammer Çavuşoğlu, in the presence of a military contingent.

The Coup of September 18, 1885

The essentially preordained union of Eastern Rumelia with the Bulgarian state was achieved through a bloodless coup on September 18, 1885 (new calendar). Since the spring of 1880, Bulgaria had allocated 800,000 francs to committees of provocateurs in Eastern Rumelia.

At the same time, a secret committee for the “union of the two Bulgarias” had been established in Bulgaria. Its agents traversed all of Eastern Rumelia in August and September 1885. On September 13, 1885, in the village of Payuritce, a center of the Bulgarian uprising of 1876, a few youths began to demonstrate in favor of unification with Bulgaria. They were arrested but subsequently freed by their fellow villagers.

The incidents began to escalate, and by September 16, they reached Philippopolis. Out of the 12 National Guard regiments, five were entirely under the control of conspirators, and in the remaining ones, all officers except for their commanders were involved.

On September 17, the unrest expanded, ostensibly over the imposition of new taxes. At 2:00 a.m. on September 18, the conspirators entered Philippopolis, firing into the air. They arrested the German Chief of the Gendarmerie, Drigalski Pasha, and at 5:00 a.m., they captured Krestovits, informing him that the people had proclaimed the union of Eastern Rumelia with Bulgaria.

Krestovits did not resist. Together with Drigalski, he was taken in a carriage to a village near the border, accompanied by a woman in Bulgarian national dress holding a sword, where they were released.

The next morning, the union of Eastern Rumelia with Bulgaria was officially declared. All men aged 18–40 were conscripted, the railway bridge over the Evros between Harmanli and the Turkish border was blown up, and the army was deployed to the borders. A delegation of Bulgarians from Eastern Rumelia was sent to Bulgaria to request that the German Prince of Bulgaria, Alexander of Battenberg, assume leadership over Eastern Rumelia as well.

Despite his initial hesitations, he eventually accepted and traveled to Philippopolis with his prime minister and aides.

International Reactions

Sultan Abdul Hamid II did not exercise the rights granted to him by Article 16 of the Treaty of Berlin and refrained from intervening. He even dismissed Said Pasha, who had proposed an attack on Philippopolis with 6,000 troops. For the Ottomans, Eastern Rumelia was already a lost cause.

The Great Powers, signatories of the Treaty of Berlin, though affected, preferred not to react. The crisis was “resolved” (?) through the Conference of Ambassadors of the Great Powers in Constantinople (November 5, 1885 – April 5, 1886). It was decided that the ruler of Bulgaria would be recognized as the governor of Eastern Rumelia, although the two countries would officially remain under different statuses.

Once again, the big loser (or the one “left out”) was Greece. The Deligiannis government demanded the cession of Crete. In Crete, the union with Greece was proclaimed once again. The Turks, enraged, sent troops to the border with Greece in Thessaly. The five Great Powers imposed a naval blockade on Greek coasts and demanded the disarmament of Greece.

On May 19 and 20, 1886, the 5th Evzone Battalion crossed into Turkish territory. However, its soldiers were captured. The battalion’s flag was saved by Sergeant Lysandros, who became a folk hero.

The Great Powers delivered a formal note to Deligiannis, informing him that the Eastern Rumelia issue was to be considered definitively closed. The Deligiannis government resigned, and the prolonged mobilization ended.

The Serbs sought to benefit from the events. However, in the Battle of Slivnitsa (on the Nis–Sofia road axis), between November 18–22, 1885, they were defeated by the Bulgarians, who invaded Serbia on November 26. Once again, the matter was resolved through intervention by the Great Powers.

It has been argued that a major mistake by Deligiannis was failing to invade further north into Epirus, from Arta, which had belonged to Greece since 1881. However, it is likely that European powers would have curtailed such an action as well.

The End of Hellenism in Northern Thrace

The events of 1885 marked the beginning of the end for the Greek population in Northern Thrace. Their annihilation was completed in 1906 with the persecutions and the burning of Anchialos and, in 1919, with the Treaty of Neuilly. We will address these events in a future article.

Ask me anything

Explore related questions