Today marks 113 years since the liberation of Thessaloniki, on October 26, 1912. On this historic anniversary, we revisit the story of Hasan Tahsin Pasha, a largely unknown yet pivotal Ottoman general — the man who chose to surrender the city to the Greeks rather than to the Bulgarians, despite their intense pressure and attempts to bribe him for a signature that would have acknowledged a joint occupation.

At his side throughout these tense negotiations was his 23-year-old son Kenan Mesare, his aide-de-camp and fluent in six languages (Greek, Albanian, Turkish, Arabic, Persian, and French). Kenan later revealed that he was offered a massive bribe to influence his father — an offer he refused outright. In 1960, he gave a remarkable interview to the newspaper Ellinikos Vorras, recounting those events. Below, we present excerpts from that interview along with a brief biography of Hasan Tahsin Pasha.

Who was Hasan Tahsin Pasha (1845–1918)

Hasan Tahsin Pasha was a senior Ottoman military officer of Albanian descent. Born in 1845 in the now-abandoned village of Mesare, near the Greek-Albanian border, he studied at the Zosimaia School of Ioannina, where he learned fluent Greek. His career began in 1870 as a rural guard in Katerini. He soon joined the Ottoman Army, rose quickly through the ranks, and by 1881 was commander of the Gendarmerie in Ioannina.

From 1889 to 1896, he served in Crete as the island’s military commander during a turbulent period, earning a reputation for justice, integrity, and efforts to ease tensions between Christians and Muslims. In 1895, he prevented the theft of the ancient Gortyn Code, an invaluable artifact that underpins modern European penal law.

During the Greco-Turkish War of 1897, he fought in Thessaly and distinguished himself in battle — so much so that the Sultan commissioned his personal painter, Fausto Zonaro, to create his portrait and battlefield scenes from Elassona, Domokos, and Pharsala.

He later served in Iraq, Syria, and Yemen, where in 1909 he successfully brokered peace after long-running local uprisings. In 1911, he was appointed commander of the 3rd Army Corps in Thessaloniki, with none other than Major Mustafa Kemal (later Atatürk) under his command.

Tahsin settled permanently in Thessaloniki with his family. His wife, Hatice Elmaz, was of Greek origin but Muslim by faith. Of their seven children, only three survived — among them Kenan, who played a key role during the city’s surrender negotiations.

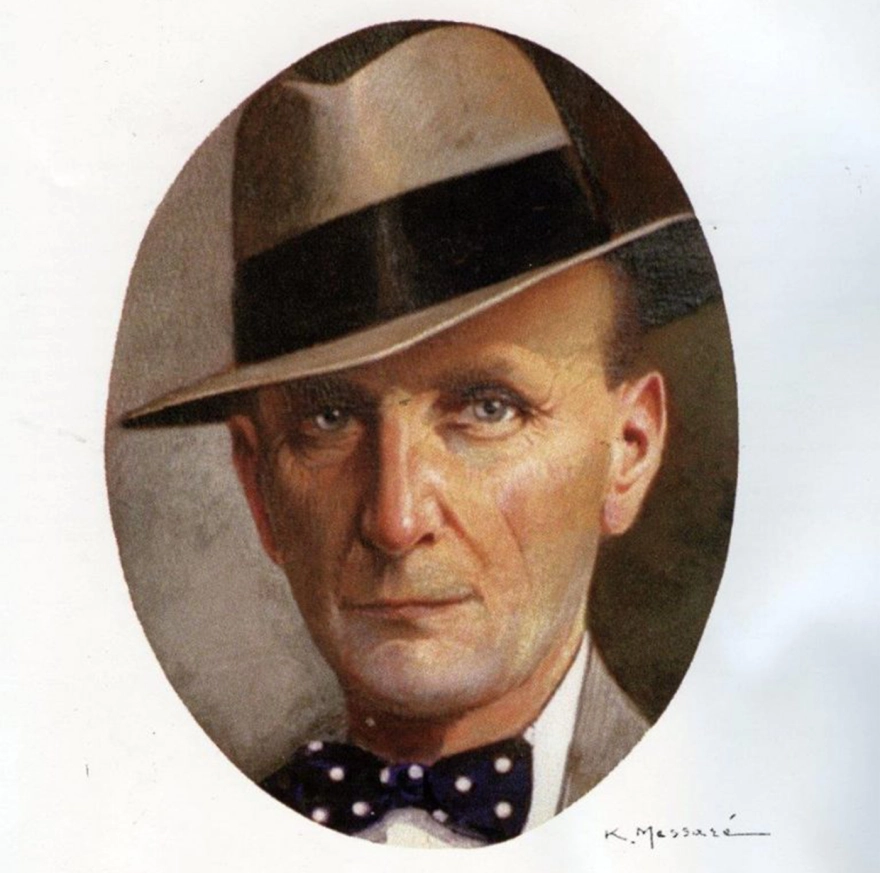

Kenan Mesare — the painter son

After the liberation, Kenan remained in Thessaloniki. In 1934, he returned to Ioannina, married the multilingual Rafet, and became known as a self-taught painter. Many of his works now belong to private collections. A new road in Ioannina bears his name today — Kenan Mesare Street.

Much of what we know about Hasan Tahsin today comes from the research of journalist Christos K. Christodoulou in his book The Three Burials of Hasan Tahsin Pasha (2007), and from historian Evangelos Kensizoglou, who examined Tahsin’s military actions and his decision to surrender Thessaloniki to Crown Prince Constantine.

The Balkan War: From Sarantaporo to Thessaloniki

At the outbreak of the First Balkan War, the aging Hasan Tahsin (then 67) commanded the 8th Ottoman Army Corps in Thessaly. The Ottoman Empire, overstretched on multiple fronts — Yemen, Libya, and the Balkans — relied heavily on poorly equipped reservists. Meanwhile, Greece had modernized its army and was determined to avenge the humiliation of 1897.

The Battle of Sarantaporo (October 9–10, 1912) proved decisive. The Germans had called the pass “the grave of the Greek army,” yet it became the opposite. The Greeks broke through with heavy losses but overwhelming momentum. Tahsin’s forces, weakened by desertions, retreated north. His final stand came at Giannitsa (October 19–20) — a fierce, rain-soaked battle where his troops were again defeated, sealing Thessaloniki’s fate.

The surrender of Thessaloniki

After Giannitsa, the Ottoman situation in Thessaloniki was desperate. Refugees flooded the city, morale collapsed, and pressure mounted from foreign consuls for Tahsin to surrender. The torpedoing of the Ottoman ship Feth-i Bülend by Greek naval officer Nikos Votsis further demoralized his troops.

Negotiations with Crown Prince Constantine began on October 24. Tahsin initially demanded to withdraw his forces armed to Karabournou (today’s Cape Epanomi), but Constantine refused — insisting on unconditional surrender. Meanwhile, Bulgarian forces were closing in from the north.

At 5:00 a.m. on October 26, Tahsin accepted the Greek terms. The Protocol of Surrender was signed around 1:30 a.m. on October 27, but for symbolic reasons — coinciding with the Feast of Saint Demetrios, Thessaloniki’s patron saint — the official record lists 11:30 p.m., October 26, 1912, as the city’s liberation time.

The next day, Greek troops entered Thessaloniki amid celebrations. Two days later, King George I arrived to formally secure the city for Greece. The Bulgarians, arriving late, were denied entry.

Why Tahsin chose the Greeks

Tahsin’s decision was pragmatic and emotional. He had fought the Greeks, not the Bulgarians; he had personal respect for Eleftherios Venizelos, whom he knew from his time in Crete; and he trusted the Greek army’s terms more. The Ottoman government later charged him with high treason, forcing him into exile. With Venizelos’ help, he escaped to Athens and later settled in Switzerland, where he died in 1918.

Sadly, many of the surrendered Ottoman soldiers sent to Makronisos died there — their remains still found decades later by political exiles.

Tahsin, Kenan, and the Bulgarians

Kenan Mesare’s 1960 interview offers a vivid account of the fateful meeting with the Bulgarian envoys who demanded co-signing of the surrender:

“We fought only the Greeks for twenty days — from Elassona to Thessaloniki. Not once did we meet Bulgarian soldiers. I was defeated by the Greeks, and to them I surrender the city. How dare you ask me to sign a protocol with you?”

When the Bulgarians resorted to bribery, Kenan recalled:

“The Bulgarian colonel handed me a check for a staggering sum — the price of a single signature recognizing joint occupation. I was thunderstruck. Trembling, I returned it at once. My father would never have accepted such dishonor.”

According to Western historians, including Richard C. Hall (The Balkan Wars 1912–1913, 2000), Tahsin summed up his stance in one line:

“I have only one Thessaloniki, and I have already surrendered it.”

Or, as recorded in Greek sources:

“We took Thessaloniki from the Greeks, and to the Greeks we shall return it.”

Ask me anything

Explore related questions