On the 27th of January, 1868, the army of the Shogunate was marching toward Kyoto. For more than a quarter of a century, the Tokugawa Shoguns had ruled Japan in peace, but now the country was once again in turmoil. Foreigners had come to Japan, Dutch, British and French, and modern European weaponry and training had for the first time become influential in the land of the rising sun. It was a turbulent time.

Japan’s politics had split the country. The young Emperor and the Shogunate were at odds, and the Emperor had caused the last Shogun to resign his post. However, the Shogun’s abdication was not enough to satisfy the clan leaders under whose influence the Emperor was acting.

(Guns of the Boshin war. From top to bottom: a Snider, a Starr, a Gewehr)

They called a meeting and declared that the very title of ‘Shogun’ was to be abolished. Tokugawa Yoshinobu, the recently abdicated Shogun, was to be stripped of all lands and titles. Yoshinobu was understandably distraught at this, and moved in force toward Kyoto, ostensibly to deliver a letter of protest to the Emperor.

His army was made up of troops from four different allied clans, and their gear reflected the rapid changes Japan was undergoing at the time. There were soldiers of the old style, colourfully dressed, elaborately armoured Samurai with pikes and spears, bows and curved swords, but also there were units of line infantry armed with rifles in the western style. Yoshinobu was not expecting a battle, but as his army approached the seat of power, the city of Kyoto, they found their advance opposed by entrenched troops of the Satsuma clan.

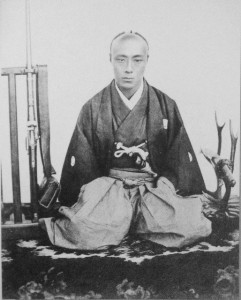

(Tokugawa Yoshinobu, the last Shogun of Japan)

The Shogun’s forces were spread out, marching along two roads separated by a range of hills and woods. Both sections of his army had bridges to cross, and both bridges were held against them. The first encounter, at the bridge nearest the city, was rapidly concluded.

Two units of riflemen and one unit armed with spears and swords found themselves opposed by nine hundred Satsuma clansmen, armed with rifles and swords and supported by four cannons. The advancing soldiers halted, and envoys were sent forward to demand that the army be allowed to pass peacefully on to Kyoto. The Shogunate rifles were empty, as the troops were not expecting a battle, but the Satsuma men refused to let them pass.

Suddenly, a burst of rifle fire came from the flank of the troops defending the bridge. These were the first shots of a conflict which would rage on for just over a year, a power struggle between the forces loyal to the Emperor, and those loyal to the last Shogun, Tokugawa Yoshinobu. The conflict became known as the Boshin War, the War of the year of the Yang Earth Dragon.

(Campaign map of the Boshin War, 1868–69)

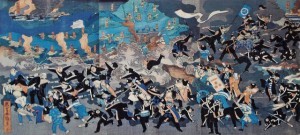

The Shogunate forces could not return fire from their empty rifles, and now the cannon at the bridge began to thunder. A shell exploded near the horse of the commander in charge of one of the units of infantry. His horse threw him and bolted. The beast charged, wild-eyed, riderless and frothing at the mouth, through the ranks of the waiting soldiers.

Confusion spread and the Shogun’s forces began to panic, but the commander of the spearmen at the front ordered them to charge the bridge. They surged forward, but the cannon and rifles of the defenders tore through their ranks as they approached. One group gained the bridge and engaged the enemy in melee, but they were killed and the survivors were driven back by the well-equipped defence.

At the second bridge, a similar Imperial force was engaged in tense negotiations with the second section of the Shogunate vanguard. When the thunder of cannon was heard at a distance, the defenders opened fire, driving this second section of Shogun’s forces into retreat.

(The first encounter ends in disaster)

The news of the battle reached the Imperial court swiftly, and by the time the shaken Shogunate forces had regrouped some miles off, orders had been drawn up and dispatched. The Emperor, so important culturally and spiritually to Japanese people, had declared open war on Tokugawa Yoshinobu and branded him a rebel and a traitor.

The Emperor authorised the troops who fought the rebel forces to carry the golden banner which represented his authority. The was a bitter blow to the morale of the Shogunate army; anyone who attacked troops under that banner would now be a traitor to the Emperor.

The Shogun’s forces retreated to the intersection of the roads and set up a command post, where they had a day to regroup. In the clear light of the next morning, a strong force attacked from the direction of Kyoto.

As they advanced, the golden banner of the Emperor came into view over the crest of the hill. The defenders were confused, not recognising the banner, and sent messages to the enemy, inquiring what the meaning of it was.

When the answer came, that not only was this the banner of the Emperor but that the army was under the command of an Imperial Prince, doubt and fear flowed through the ranks of the Shogunate troops like fire through dry grass. The Imperial family was – and is – an incredibly powerful symbol in Japan. For a man to fire on forces under the Imperial banner was no small matter for his conscience.

(The retreat of the Shogunate forces, anonymous painting c. 1870)

The campaign did not progress well for the last Tokugawa Shogun and his allies. Despite the awe inflicted upon them by the banner of the Emperor, they resisted, but confusion had permeated the ranks, and they could not effectively challenge their attackers. Over the next few days, they fell back, again and again, passing north toward the fortress-city of Osaka.

The Boshin war had begun, and by the end of the next year, it would have claimed more than three and a half thousand lives. Yoshinobu of the ancient house of Tokugawa was the last to hold the title of Shogun in Japan. After this early battle, clan after clan joined the Emperor’s cause, and the Shogun’s opposition was quashed by early the next year.

(Samurai of the Satsuma clan during the Boshin War, by pioneering military photographer Felice Beato)

Change continued apace in Japan, and the last days of the old way had passed forever. The Tokugawa Shogun was spared along with many of his officers, but while many of them took positions in government, he retired into a life of quiet retreat. The last Shogun died in 1913, at the age of 73.

Ask me anything

Explore related questions