Every medieval English monarch had to decide how to deal with prisoners of war. Ruling over territory that sometimes ran from the highlands of Scotland to the south of France, their authority rested on violence. Fighting the French, Scots, Welsh, Irish, or their own nobility in a string of civil wars, they could not have kept their throne without victories on the battlefield.

How, then did they deal with the warriors they defeated?

Ransoms

From early in the Middle Ages, paying a ransom was an important principle of warfare. After a battle, prisoners expected to be able to buy their freedom. It could be a costly business – a king who lost good men and spent his wealth fighting would want compensation. The son of the Constable of Richmond Castle had to pay 200 marks after his father’s castle was seized in 1216.

Prisoners usually remained in captivity until their relatives could gather the ransom. Occasionally they were freed temporarily to raise the payment themselves, as happened with some of the prisoners after the Siege of Carrickfergus in 1210. Once the money was forthcoming, conditions might be attached to a person’s release, such as not making war again.

This system worked well for everybody involved. Those who took captives were given a chance to profit from being merciful. Knights could fight in the knowledge that if they lost, they would not be killed out of hand. They could expect to be treated reasonably well while they were in captivity. When a prisoner was mistreated, as in the disappearance of King John’s nephew Arthur of Brittany, it became a source of scandal.

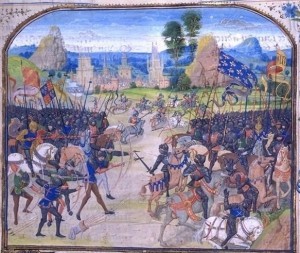

(Battle of Poitiers, 1356)

Chivalry

In the 14th century, existing and ill-defined rules of war evolved into something more sophisticated – the concept of chivalry. Writers such as Geoffroi de Charny took ideas about correct knightly behavior and tried to define them clearly. It created a system that was part rules of war and part guide for gentlemanly conduct.

Much of the writing originated in France, although it had a significant influence in England. Only one in ten of the mounted and armored soldiers fighting in the Hundred Years War held the rank of Knight, the rest being men-at-arms. The rules were extended to include those combatants as well.

Chivalry formalized the ransom system, emphasizing the honor involved. It also encouraged institutions such as the English Court of Chivalry, which helped settle disputes over payments. Prisoners such as the French King John, captured at the Battle of Poitiers in 1356, could expect to be treated with clemency due to their financial value and the importance of a chivalrous reputation.

The Limits of Chivalry

Both chivalry and the earlier ransom system had their limits.

Certain types of troops were considered exempt from any rules of war. For example, King John butchered the archers captured during the Siege of Rochester in 1215. It was regarded as acceptable because of their social class and also because Pope Pious III had condemned the use of bows in war.

Towns and castles which resisted during a siege and were then captured were exempt from mercy. It was formalized in the chivalric rules of the 14th century, allowing besiegers to use the threat of slaughter to end things quickly.

There were times when the lenient treatment of prisoners was deliberately withheld, and leaders who usually paid attention to chivalry would forgo it when they felt it necessary. At the Battle of Crécy in 1346, King Edward III ordered that no quarter be given, to ensure his men would not be distracted hunting ransoms. At Agincourt in 1415, Henry V ordered prisoners to be slaughtered during the battle.

(Portchester Castle, England)

Fighting on the Fringes

The Celtic fringe of Britain proved a particularly merciless region. The English regarded the Welsh and some of the Scots as barbarians. These were people who neither knew nor followed the rules of “civilized” warfare. It was, therefore, acceptable to treat them harshly leading to acts of slaughter on both sides.

When the Welsh captured an English castle in 1212, all the prisoners were beheaded. The English were already treating the Welsh the same way, executing rather than ransoming prisoners. The execution of Walter Selby and his sons by the Scots was condemned by the English. Many believed the killings led to the Scots’ defeat at Neville’s Cross in 1346, as an act of judgment by God upon the murderers.

Dealing with Rebels

The treatment of rebels and captives from civil wars changed over the course of the Middle Ages.

During the revolt against King John, his advisors persuaded him not to kill noble prisoners, something he had proven willing to do in the past. During the Barons’ Revolt of the 1260s, there was a similar level of restraint. The leader of the rebels, Simon de Montfort, died in battle, but his followers were spared. Even their fines and confiscated property were less than in later rebellions.

By the time of Thomas of Lancaster’s revolt against Edward II in 1321-2, attitudes had changed. Rebellion against the Crown was not treated as a form of political expression. It was an act of treachery to be punished. Lancaster and the other leaders of the revolt were executed. Instead of facing ransoms and fines, rebels became outlaws or corpses, their bodies left on display as a lesson.

This may have been due to the wars with Scotland and Wales, which blurred the line between rebellion and the conquest of “barbarians.” The execution of William Wallace in 1305 was a particularly brutal act against a prisoner of war who was both an outsider and an insider, a Scot and a knightly rebel.

On the other hand, it may have been monarchs became more brutal to assert their control and repress dissent.

In Medieval England, wealthy and powerful prisoners of war could usually expect to be treated well. They were released in return for money, as long as they were not regarded as rebels or barbarians. For the rest of the poor soldiers, it was a matter of luck. They might be freed, or they might face execution as a lesson to others. Which way the dice fell was not in their control.

Ask me anything

Explore related questions