How the daughter of Nicholas Gatzogiannis, the author of the famous book on Civil War, faced the ghosts of the past and overcame the family heritage of the horror of the executions.

This burden her name carries is both a blessing and a curse, but fortunately enough, “Eleni N. Gage” is a guarantee.

Particularly when she praises our country, for example, writing “Condé Nast Traveler” to the world’s leading travel journal, “I want to hear Greek, to taste juicy tomatoes and to drift in conversations I have been doing since I was very young and we lived in Athens. Every year, friends who are looking for a “truly unique experience” ask me what’s the most “fresh”, the most wonderful Greek island.”

In this case, in “Condé Nast Traveler”, Eleni speaks about Milos, but in any case her style and tone are not far from the hymns she writes every time about Greece.

Eleni Gatzogianni was born in America where she grew up, while she studied Mythology and Folk Culture. And while she had initially developed a spontaneous aversion to anything that had to do with her grandmother’s martyrdom, she eventually wrote her own “Helen” looking for a way to talk with her, albeit completely different from the way Nicholas Gage chose.

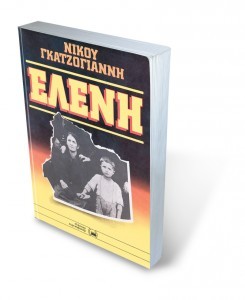

(Nicholas Gatzogiannis’ book has been an international best-seller, translated into 32 languages)

Eleni N. Gage writes:

“My grandmother, having left alone in her village, Lia, was arrested, imprisoned, tortured and executed because she organized the escape of her children. Communist guerrillas had occupied my grandparents’ house and made it their headquarters because it was the largest in the village. But the guerrillas wanted to punish my grandmother because her husband was working in the USA. That is why she and her family were convicted. With her four children fleeing to a refugee camp and the fifth, the then 15-year-old Lilia, to cook wheat for the rebels in a distant village, my grandmother spent the last few weeks of her life without her family but at her home. The soldiers sent local women and younger girls to do hard work, gave military training to girls, and eventually began to take children from their parents. They sent them outside of Greece, behind the Iron Curtain. The guerrillas were losing the war, but they had the hope that by taking children and installing them elsewhere, and if they infused their own principles and given them military training, they could have reached a greater victory. My grandmother, having learned about this mass kidnapping of children project, tried to organize her children’s escape to the USA. Her husband had migrated there before the start of WWII.”

In this way she explains why the name “Eleni Gatzogianni” was by definition an almost unbearable heritage and an unavoidable task: that name had to do something, urgently – and indeed this is how she felt after a point in her life. Something that must certainly contain Greece and the traumatic history of a whole nation, the tragedy of the Civil War, the pain through which her family identity has been built since 1948, when that first Eleni Gatzogianni was executed by the communists.

Young Eleni Gatzogianni first started as a writer in glamorous women’s magazines writing for fashion, beauty, and so on, before turning to writing and travel literature. At the same time, she started a family with a Nicaraguan coffee merchant and has two “Greekaraguan” – as she describes her young children. She travels all over the world and definitely once a year in Greece. With the exception of two quite long periods when he moved to our country, Nicholas Gatzogiannis’ daughter lives permanently in Worcester, Massachusetts.

Eleni N. Gage, as she is known, has in recent years voluntarily assumed the duties of an informal ambassador of Greece. She tells in every occasion and all over the world the beauty of our country, her distant homeland, her own and her ancestors’, with great enthusiasm: “If I had signed a premarital agreement, it would contain the condition that every year my husband, Emilio, should accompany me to Greece”, was the phrase by which Eleni Gage chose to start her tribute to Milos in “Condé Nast Traveler”.

(On vacations with her husband and her father)

What she ended up doing today in the name of Greece, the younger Eleni, could never be done without the enormous resonance that her father’s book “Helen” had, which was a global success, even surprising the author himself. His work has so far been translated into 32 languages, has sold millions of copies, and has even become a film starring one of the top American actors, John Malkovich, who played Nicholas Gatzogiannis and was really traveling through Greece – but not in the real village of Lia, because it was not given the permission to shoot on the spot, in the fear of dangerous excitement of the spirits… When the book was reissued in Greece in 2004, prologue notes were signed by political figures who had held important offices in the government, such as Karolos Papoulias (later Greek President) and former Prime Minister Konstantinos Mitsotakis.

Things, of course, were quite different when “Helen” was translated into Greek for the first time, shortly after its original English version in 1983. In the spirit of the “national reconciliation” cultivated by the then dominant PASOK government, “Helen” unintentionally triggered the political divide, revealing that the soil in which the civil passions had been buried was rather light. The book was demonized, the Left tried in every way to boycott its dissemination by denouncing Gatzogiannis for fanaticism, bias, distortion of historical truth, etc. Demonstrations were also organized against the film outside cinemas. There was also a book written by the reporter Vassilis Kavathas entitled “The Other Eleni”, on the other side, aiming at restoring the “lies” of Gatzogiannis.

Nevertheless, for Nicholas’ daughter, a subconscious need, a debt, was formed: one Eleni had to meet her ancestor again, executed, so prematurely (just to her 41-years-old) grandmother, to feel the similarities between them as well as the twist of fate, with everything that can unite two completely different women in two completely different times and conditions, who however, have the same name and, of course, the same blood. “In 1980 I had realized that I had to dedicate myself immediately and exclusively to investigating the history of my mother or abandon it forever,” wrote Nicholas Gatzogiannis. And he himself pointed out why his daughter was the natural continuity of dead Helen: “In 1980 I was 41 years old, at the same age as my mother when they killed her. My son was nine as I was the day I learned her death. My oldest daughter, looked every day more and more with my mother.”

The house of “ghosts”

The bet for Eleni Gatzogianni has little to do with that of her father’s forty years ago. As she would write long after the late 1970s, when Nicolas went on in his research, “since I was six, I knew I had no intention of reading the story of how she lived and how my grandmother died. Between my three and seven years I lived with my family in Athens, as my father did his research for his book.”

And Eleni Gatzogiannis goes on to discribe an extremely unpleasant memory from her childhood years in Greece:

“I will never forget the moment when a middle-aged man from Vavouri, a village in Epirus next to Lia, had come to visit us. He offered me an ION chocolate and went to the living room. There he sat with my father and told him how the communists had tied up his parents to a tree and they had shot them during the Civil War. I sat on the stairs and ate my silky chocolate with its pink, white and red wrap. I was listening to the story of that man, unnoticed and terrified. And it was then that I decided to avoid, as much as possible, the elderly Greeks with sad looks and traumatic memories.”

“The wolves and scorpions will eat in Lia, they will rape you…”

Nevertheless, in 2001 she surprised herself and the four sisters of her father, who insisted – as if in an ancient Greek tragedy- to “stay where you are and settle with a Greek. In Lia, the wolves and scorpions will eat you, they will rape you”. Quite suddenly, however, Eleni Gatzogianni decided to resign from the magazine she was working for and to settle for a second time in her life in Greece. And not in Athens or in some of the sunny and “prospectus islands”, but in Epirus, in Lia. She had decided to resurrect the old stone house of Grandma Eleni, where she was tortured, where they took her from one morning to take her to the place of her execution.

“I wanted to transform the ruins into a house so that if my grandparents’ ghosts ever returned, they would recognize it as their own. In addition, I was thinking that if I lived in the village where my grandmother spent her entire life, it would help me feel like I knew this woman I never met. I had her name, but I did not know her. Living between Eleni’s neighbors, I would probably know better the Greek side of my soul”.

These were written by Eleni Gatzogianni in her book “North of Ithaca”, her own indirect autobiography. It is a diary, sometimes light and sometimes dark, about how an American woman appeared in a small village in the Greek province and managed in ten months to renovate the home of her ancestors.

(Nicholaos Gatzogiannis with Amal Alamuddin-Clooney at her visit in the Acropolis Museum on October 2014)

“We must kill a cock”

The reader watches the whole adventure of rebuilding with comic-tragic episodes in which Eleni confronts the sometimes surreal Greek mentality, bureaucracy – and strange…customs. She even reached her limits when, in spite of her horror, she eventually had to come to terms with the idea that a cock “for the good of the building” had to be slaughtered.

The biggest fear she had to overcome to complete the renovation, on a deeper level, was to come closer to the truth about what happened in that same space during the Civil War, the basement of the house.

“There, in the basement of my own house, my grandmother spent the last few days. She wondered if she would be the next they would take to torture or execute and bury. In this basement the prisoners lived in the terror and pain. That scared me more than anything else. The whistling of the air through the trees was like the screams of the prisoners to my ears. It was true: I was afraid of the ghosts. And that’s why I wanted to go back to Lia, to take the house back from the ruins and myself from my phobias. My own and the even worse of my aunts and my father”.

Eleni Gage finally restored her grandmother’s home, even if she did not turn it into a viable ecotourism hostel. In the course of her effort, she overcame all sorts of obstacles and, above all, the horrors inherent in her soul by the ancestors with narratives, but also by their own lives.

In “Helen”, as described in the last pages of his work, Nicholas Gagez experienced his ultimate dilemma whether or not to pull the trigger on the weapon he had taken with him, going to meet the one he hated like no one else. He had identified the man who, in his capacity as the communist civil judge, had sent his mother Eleni to execution. Revenge, lynching with his bare hands the man you killed the woman who gave birth to him, was an incentive for the Greek-American journalist and writer. An incentive as powerful as the full disclosure of the truth, around the black pages of Civil War in Greece. Finally, he did not drench his hands in blood, which he justified by writing:

“I know that fear has stopped me, in part the fear that my children would be separated, and that I set in motion events that would perpetuate the killings and the misfortunes to future generations. But there was something else: the understanding of my mother that the research of her life had given me. Unlike Hecuba, my mother did not use her last moments by cursing her torturers, but as Antigone found the courage to face death because she had done her duty to those she loved. Antigone of Sophocles says to the one who sentenced her to death, her uncle and king: “In this world I was not born to hate, but to love”.

Little Eleni and the Grandma

Gatzogiannis, shortly before letting the reader draw his own conclusions as he completes his shocking narrative about the hard life and even more cruel death of Elena’s mother, cuts off the critical moment this existential dilemma by writing: “If I killed the ‘judge’ of Helen, I would have to uproot her love from within me and become like him, to wither as he did all humanity and pity. As he had left his baby daughter and his wife to become a killer for the communists, I should also put aside all thoughts about what I would do to my children’s lives. My mother out of love for her children had done everything”. In a strange way, Nicholas Gage addressed the dead Eleni and her granddaughter. That’s because, while he was looking for the innocent and the guilty among the living and the ghosts, little Eleni was already beside him – but not exactly. She, a genuine American, wanted deeply to talk, meet and love her grandmother. Helen, who marked and determined, unknowingly, the life of her grandchild bearing the same name. Helen, who the communists with depreciation called the “American,” because she wanted to protect her children from being kidnapped by them and for this “crime” she was tortured and murdered.

Ask me anything

Explore related questions