The American West has long been a place for cowboys, gunslingers, and hidden treasure. However, there’s been questions about the true fate of certain outlaws along with other mysteries that have fascinated people for around a hundred years and that have never been solved or explained by modern historians.

Butch Cassidy’s Death

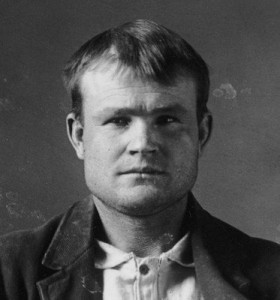

(Cassidy’s mug shot from the Wyoming Territorial Prison in 1894)

Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid robbed trains, banks and stole horses in the 1890s Wild West. Even though the record states that the notorious bank robbers were killed in a gunfight with the Bolivian military after fleeing the US, many of Cassidy’s friends and family members state that he actually visited them a couple of times after he was said to have been killed. Documents revealed by historical researchers suggest that the confrontation with Bolivian authorities happened in a home while Cassidy and his gang were sorting through the spoils of a payroll heist. Two men were dead in the end, but it’s been suggested that neither of them was actually proved to be Cassidy or the Sundance Kid. The bandits were identified as the men who robbed the Aramayo payroll transport, but the Bolivian authorities didn’t know their real names, nor could they certainly identify them.

Victorio Peak Treasure

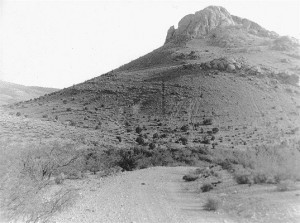

(Victorio Peak, Southern New Mexico)

The Victorio Peak Treasure is one of the most famous treasures in the United States, second only perhaps to the Lost Dutchman Mine.The origin of the treasure is unrevealed. It’s believed it could be the lost treasure of Juan de Onate, the man who founded New Mexico as a Spanish colony. Another theory is that it belonged to a Catholic missionary named Father LaRue who once operated gold mines in the area. It’s also been linked to Maximilian, the Emperor of Mexico, and to the Apache Indians who raided stagecoaches heading to California. The legend of the Victorio Peak Treasure begins in the 1600s when a dying soldier stumbled into a New Mexico monastery and confessed his knowledge of a secret cache of gold ore in the mountains to a monk named Padre Felipe LaRue. So, the LaRue put together a group of people and found the mine where he and other members of the group successfully mined gold for three years. When the Mexican Army was sent to overtake LaRue’s operation, he ordered workers to close the entrance to the mine with a landslide. LaRue and his band of miners died without giving out the information regarding the mine entrance.

Bill Longley’s Execution

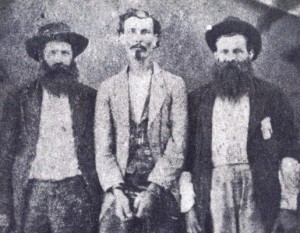

(Bill Longley captured, June 6, 1877)

“Bloody Bill“ Longley had more than 30 killings to his name before he was hanged at the age of 27, suggesting that Longley was one of the most dynamic and lunatic gunslingers in the Wild West. He was arrested in 1873, but when the reward wasn’t paid, he was set free. Three years later he was arrested again but escaped in the confusion after setting the jail on fire. On June 6, 1877, Longley was surrounded and arrested and on October 11, 1878, he was executed by hanging in Giddings, Texas, only a few miles from his birthplace of Evergreen. It is rumored that the “Bloody Bill“ escaped before being killed. Years after the execution, Longley’s father, Campbell, came forward in a press release stating that his son had not been executed. He claimed that a wealthy relative in California bribed the lawmen with $4,000, prompting them to rig a trick rope. They then staged the hanging and carried the body away. This prompted many historians to investigate. Numerous myths and legends have grown up about Longley that cannot be verified by any contemporary source.

Cochise’s Burial Site

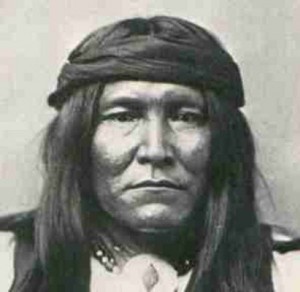

(Cochise -c. 1805 – June 8, 1874- was a leader of the Chihuicahui local group of the and principal of the Chokonen band of the Chiricahua Apache)

Chief Cochise is one of the most well-known figures in the conflict between the Native American people and the European settlers. Almost nothing is known about his life before the middle of the 19th century when he was already established as the leader of the Chiricahua Apaches in the areas of northern Mexico and southern Arizona. After making peace, Cochise retired to his new reservation, with his friend Jeffords as an agent where he died of natural causes on June 8, 1874. He was buried, in a traditional ceremony along with his horse and dog somewhere in the rocks above one of his favorite camps in Arizona’s Dragoon Mountains, now called Cochise Stronghold. Only his band and Tom Jeffords knew the site. They took this knowledge to their own graves, telling no one of the place where Cochise had been buried and the location of his actual burial ground remains unknown.

Lost Dutchman’s Gold Mine

(In many versions of the story, Weaver’s Needle is a prominent landmark for locating the lost mine)

It’s perhaps the most talked-about lost treasure in American history, but there seems to be more myth than fact surrounding the gold. The Lost Dutchman’s Gold Mine is, according to legend, a rich gold mine hidden in the southwestern United States. The mine is named after German immigrant Jacob Waltz (c. 1810–1891), who purportedly discovered it in the 19th century and kept its location a secret. After he died in 1891, gold miners went searching for the location of the mind and every year since his death, visitors have continued to do so. However, the gold mine was never found and some have died on the search.

Pancho Villa’s Head

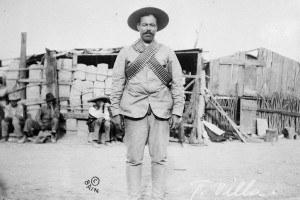

(Villa wearing bandoliers in front of an insurgent camp)

Francisco Villa, better known as Pancho Villa went from being a bandit to a leader in the military over his lifetime. By the end of his life, he was one of the most infamous figures of the Mexican Revolution. After he retired from military life, he was assassinated in an ambush in 1923. He was buried in Chihuahua, Mexico at Hidalgo del Parral. Three years later, his tomb was broken into and his body was decapitated. Grave robbers exhumed his body and removed parts of the corpse – specifically, his head. It’s never been discovered what happened to his head, but there are many stories and rumors. When his remains were moved in the Monument to the Revolution in Mexico City in 1976, his family says only a few bones were left.

Thunderbirds

(The Thunderbird photograph that is most circulated. However, many people believe that the real Thunderbird photograph is still a mystery)

Claims of giant winged birds that resembled pterodactyls were prolific in newspaper articles in the late 1800’s in California and Arizona. A photo of one such beast nailed to a barn in Tombstone is said to have been widely circulated, though nobody has ever been able to produce a copy of the image. Numerous researchers, investigators, and authors of a whole range of anomalies claim, with absolute unswerving certainty, that they personally saw the priceless picture when it was published. However, the picture cannot be found. It’s almost as if it never even existed in the first place. Wild West author and investigator W.C. Jameson said he has one of the original feathers in his collection, asserts that the feathers have been examined by a number of ornithologists, but that the species responsible for producing them has yet to be identified.

Billy the Kid’s Death

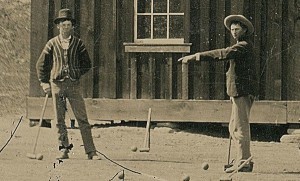

(Detail from a photo authenticated in 2015 of Billy the Kid (left) playing croquet in New Mexico in 1878)

Billy the Kid was easily the most notorious desperado of the Wild West. He reportedly killed 21 men, one for every year of his young life. According to Wild West knowledge, Billy the Kid was tracked down to a residence in Fort Sumner by Sheriff Pat Garret, where he was shot and killed. However, in 1948, a man in Central Texas known as Ollie Partridge Roberts (nicknamed Brushy Bill) claimed to be Billy the Kid; his claims were dismissed by the governor of New Mexico and his own family. He died without proving his identity. A statistical facial recognition analysis comparing Roberts to known images of The Kid suggested that the two men were actually one and the same.

The Desert Ship

(No one knows for sure, but the legend of the Lost Ship of the Desert has become one of the Southwest’s most tantalizing tales)

The Lost Ship of the Desert is the subject of legends about ancient ships found in California’s Colorado Desert. After the U.S. Civil War, stories have been told about buried ships hidden in the desert lands north of the Gulf of California. On December 1, 1870, a man named Charley Clusker claimed to have found an extraordinarily well-preserved Spanish galleon, but nothing was ever brought back from his expeditions into the desert. Since then only a handful of explorers have tried to find the ship and its booty again but none of them have produced evidence that either the ship or its cargo exists. Of course, it will never stop people looking for it.

Queho

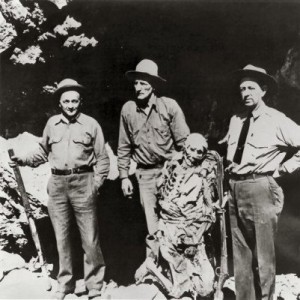

(In 1940, prospectors working near the Colorado River discovered a cave containing the mummified remains)

Part myth-part man, Queho was an enigmatic figure who wavered between serial killer, boogeyman, and scapegoat. Not much is known about his early life—or his life at all. He was born sometime in the 1880s, the child of a Native American mother and an unknown father. His mixed heritage made him an outsider from the beginning. During his lifetime, Queho (pronounced KEY-ho) was credited with the deaths of 23 people, was declared Nevada’s “Public Enemy No. 1,” and the state’s first mass murderer. Queho may have been treated as an outcast due to his mixed race or due to a leg deformity or clubfoot. Another report says that a badly healed broken leg caused him to leave distinctive tracks. Spanish speaking Indians gave him the name which is a derivative of the Spanish for grumbler or complainer. On February 19, 1940, a corpse with a double row of teeth was identified as Queho. His bones were taken on tour before being buried in an unmarked grave in the public portion of the local cemetery.

Ask me anything

Explore related questions