Arkansas is on the verge of banning the use, during the growing season, of a Monsanto-backed weedkiller that has been blamed for damaging millions of acres of crops in neighboring farms this year.

The weedkiller is called DICAMBA. It can be sprayed on soybeans and cotton that have been genetically modified to tolerate it. But not all farmers plant those new seeds. And across the Midwest, farmers that don’t use the herbicide are blaming their DICAMBA-spraying neighbors for widespread damage to their crops — and increasingly, to wild vegetation.

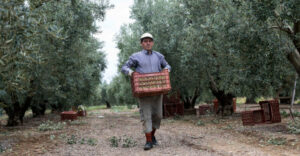

(David Wildy, a prominent Arkansas farmer, in a field of soybeans that were damaged by DICAMBA. He says that “farmers need this technology. But right is right and wrong is wrong. And when you let a technology, a pesticide or whatever, get on your neighbor, it’s not right. We can’t do that.”)

The issue has driven a wedge through farming communities in the Midwest, straining friendships and turning neighbors into adversaries.

Monsanto turned to DICAMBA because many weeds have evolved resistance to the company’s earlier weed-killing weapon of choice, glyphosate, also known as Roundup. Increasingly, Roundup no longer gets rid of farmers’ most troublesome weeds.

DICAMBA is an old herbicide, but it’s now being used much more widely, in combination with a new generation of genetically modified, DICAMBA-tolerant crops. It’s also being widely used, for the first time, in the heat of summer, which makes the herbicide more prone to “volatilizing” — turning into a vapor and drifting in unpredictable directions.

This was the first year that farmers were allowed to spray it on soybean and cotton fields. (Some farmers did use dicamba illegally last year, provoking disputes between farmers that in one case, led to murder.) Many farmers embraced the new tool. But it quickly turned controversial: Farmers couldn’t seem to keep DICAMBA confined to their own fields.

The problem was worst in Arkansas, where almost 1,000 farmers filed formal complaints of damage caused by drifting DICAMBA. But the rogue weedkiller has hit fields across soybean-growing areas from Mississippi to Minnesota.

According to estimates compiled by weed scientist Kevin Bradley at the University of Missouri, at least 3 million acres of crops have seen some injury. Most are soybeans that aren’t resistant to DICAMBA, but vegetable crops like watermelons, fruit trees and wild vegetation have been injured as well. The DICAMBA vapors didn’t typically kill the plants but left behind curled leaves and sometimes stunted plants.

“There is no precedent for what we’ve seen this year,” says Bob Scott, a weed specialist with the University of Arkansas.

(Ty Vaughn, a top Monsanto executive, speaking to the Arkansas State Plant Board meeting this week)

The Arkansas State Plant Board now has taken the lead in cracking down on the problem. On Thursday, it voted unanimously to ban the use of dicamba on the state’s crops from mid-April until November. This amounts to a ban on the use of DICAMBA in combination with Monsanto’s genetically engineered crops. It’s not a final decision: The governor and a group of legislative leaders have to sign off on the Plant Board’s regulatory decisions, but they usually do so. That won’t happen, however, until after a public hearing set for Nov. 8.

The board also approved a steep increase in fines — up to $25,000 — for farmers who use DICAMBA and similar herbicides illegally.

Monsanto insists that its version of DICAMBA, which the company has mixed with an additive that’s supposed to make it less volatile, does not drift from the fields where it is sprayed if farmers use it correctly. The company sent a delegation of five people, including Ty Vaughn, a top executive, to this week’s meeting of the Plant Board. They passed out binders and thumb drives filled with data from the company’s own tests — tests that convinced the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency to approve the chemical on crops.

Vaughn told the board that most of the damage from DICAMBA comes from farmers not understanding or following the rules for using it properly. “There’s going to be a learning curve,” he said. “It behooves all of us to continue to learn, and work toward solutions. I hope that’s the goal of everybody in the conversation.”

For Monsanto, a lot of money is at stake — potentially hundreds of millions of dollars. Nationwide, Monsanto sold enough DICAMBA-tolerant soybeans to cover 20 million acres this year, and the company expects that number to rise.

But Monsanto may have underestimated the backlash against DICAMBA in Arkansas. The Plant Board was convinced by field experiments carried out this summer by researchers at the University of Arkansas and other universities. Those tests showed that DICAMBA — even new formulations created by Monsanto and another chemical company, BASF — does vaporize and spread across the landscape.

David Wildy, a prominent farmer in Manila, Ark., who served on a state-appointed task force that recommended the ban on DICAMBA use on crops, says that “farmers need this technology. But right is right and wrong is wrong. And when you let a technology, a pesticide or whatever, get on your neighbor, it’s not right. We can’t do that.”

(Richard Coy manages 13,000 honeybee hives in Arkansas, Missouri and Mississippi. In this location, his hives produced only half as much honey as usual. Vegetation nearby was heavily damaged by DICAMBA)

After Thursday’s vote, Monsanto’s Vaughn sounded defiant, accusing the Plant Board of ignoring scientific data. “The most troubling thing is, we did come in good faith to try and provide more information — the binders and the flash drives — and clearly they did not even consider that information before they made their decision,” he said. He said that the company was “keeping all options open” in deciding how to respond. Monsanto has previously threatened to go to court if Arkansas went ahead with a DICAMBA ban.

In recent weeks, others have also started reporting damage from DICAMBA. These include gardeners, beekeepers and wildlife advocates.

The most impassioned speaker at this week’s meeting of the Plant Board, in fact, was Richard Coy, who manages 13,000 honeybee hives in Arkansas, Missouri and Mississippi. Coy reported that in areas where farmers were spraying DICAMBA on their crops, honey production in his hives fell by 30 to 50 percent, apparently because DICAMBA stopped wild vegetation from blooming, thus depriving bees of sustenance.

“Yes, it’s just weeds and vines,” Coy told the board. “But those weeds and vines are there for a reason. This is about the environment. If we don’t get a handle on it, our natural environment will not be the same.”

Other states, and the EPA, are considering new restrictions on dicamba use. But so far, none have come up with specific proposals.

Source: npr.org

Ask me anything

Explore related questions