It was a clear October night in the hills above Kythrea and 19-year-old Jamie Eykyn was settling in for a long and uneventful evening. Standing sentry before a single-storey Army complex in the Cyprus countryside, the young Grenadier Guards officer had little to see and nothing to hear except the swish of the Mediterranean breeze through the olive groves.

Until, that is, the night air was pierced by sounds that still chill his blood today, six decades later – agonized screams from the men held prisoner in the building he was guarding: a British interrogation center.

This was 1958 and EOKA fighters were mounting an armed insurgency in their fight for Cypriot independence from colonial rule and, as Lieutenant Eykyn would discover to his horror, Britain’s response was uncompromisingly brutal.

Now aged 79, Mr Eykyn is speaking for the first time about the horrific events of 60 years ago – and about the shameful cover-up that followed.

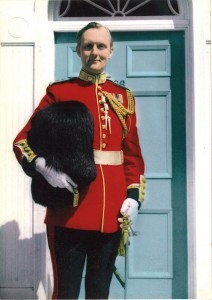

(The night air was pierced by sounds that still chill his blood today, six decades later – agonized screams from the men held prisoner in the building he was guarding: a British interrogation center. Now aged 79, Mr Eykyn (pictured) is speaking for the first time about the horrific events of 60 years ago – and about the shameful cover-up that followed)

Outraged by what he witnessed, he told his superior officer, Major Michael Stourton, who in turn, alerted the authorities.

Yet instead of gratitude for their bravery, they met a wall of hostility: Major Stourton was ostracised, cold-shouldered by some fellow officers for speaking out and effectively silenced by Ministry of Defence censors, who saw fit to remove the episode from the official history of the Grenadier Guards.

For more than half a century it has remained a secret – until now.

Indeed Mr Eykyn is not alone in his testimony, for he is supported by the family of the late Major Stourton, his friend and former colleague.

Determined to help uncover the abuse at Kythrea and the subsequent whitewash, they have opened up Major Stourton’s damning evidence from the family archive so that the truth can finally be told about a dark chapter in British history.

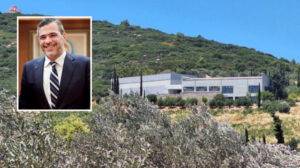

(Outraged by what he witnessed, he told his superior officer, Major Michael Stourton, who in turn, alerted the authorities. Yet instead of gratitude for their bravery, they met a wall of hostility: Major Stourton -pictured- was ostracised, cold-shouldered by some fellow officers for speaking out and effectively silenced by Ministry of Defence censorship)

Major Stourton died in 2001, but left a full account of the episode in his papers, now released for the first time to The Mail on Sunday.

Already shamed by the violence of post-war rule in Kenya, Britain today faces questions about its troops in Cyprus, too, with 34 Greek-Cypriots mounting a legal challenge claiming they were victims of mistreatment including beatings, waterboarding and rape by colonial forces trying to keep a lid on EOKA’s insurgency.

By the time 32-year-old Major Stourton and the second Battalion of the Grenadier Guards were despatched to the island in May 1958, Cyprus was in ferment. The troops had initially been sent there on their way to help King Hussein of Jordan, whose reign was under threat from attempted coups. Instead, the battalion was asked to help with security patrols against EOKA, whose assassination squads had murdered British soldiers.

In October that year Major Stourton was ordered to send one of his platoons to Kythrea to guard what he had been told was an interrogation center.

There, he spoke to a man in plain clothes who described himself as a ‘District Intelligence Officer’ and asked him to keep the Grenadiers a certain distance away so they would not hear the sounds of Cypriots being interrogated during the night.

But not only did they hear the screams, the Grenadiers witnessed some of it, too, as Mr Eykyn explains. He recalls: ‘At night, they would put the detainees into a big barn. The interrogation hut was on one side of the barn and it was not under our control. I heard screaming coming from it, and one of my guardsmen did, too.

‘It was a terrible sound.’

The following day, he discovered a young man lying on the floor with a ‘pure white’ face,

‘I couldn’t see any bruises on him but I knew something had happened to him,’ he says. ‘I got on my radio and asked Michael [Stourton] to come up, and to bring some blankets and medical supplies. I reported my misgivings because I was deeply unhappy about what was going on.’

Three days later, he found several ill Cypriots slumped against a wall, and far more damning evidence soon followed. One soldier in the platoon witnessed torture actually taking place. He told Lt Eykyn how he had seen a prisoner’s head being held back as he was repeatedly struck on the throat. He was struck on the stomach, too, and the backs of his knees with blocks of ice.

(Already shamed by the violence of post-war rule in Kenya, Britain today faces questions about its troops in Cyprus, too, with 34 Greek Cypriots mounting a legal challenge claiming they were victims of mistreatment including beatings, waterboarding and rape by colonial forces trying to keep a lid on EOKA’s insurgency)

Two days later, the Greek man in charge of the center’s administration told him that one prisoner had died under interrogation and that they had put ice next to the body when beating him so that there would be no sign of bruising. Mr Eykyn says: ‘He said, “We’re saying he died trying to escape.” I thought, “This is not right.”

Not everyone agreed with him, however. Some in the officers’ mess believed that, as suspected “terrorists”, the detainees deserved whatever treatment was meted out.

‘The night I heard the screaming, one of the other officers totally disagreed with my attitude,’ Mr Eykyn recalls. ‘I told him, “We’re not here to reinvent the Nazi tactics of the Second World War.” It wasn’t us [the Grenadiers] mistreating the prisoners. But it was being done in the name of the British Armed Forces.’

Troubled by Lt Eykyn’s evidence, Major Stourton returned to Battalion Headquarters to report what he had seen, but the Commanding Officer, Colonel James Bowes-Lyon, a cousin of the Queen Mother, was not there. Major Stourton decided to drive to Government House to speak to a friend who worked as Private Secretary to the Governor, Sir Hugh Foot.

Mr Eykyn says: ‘Michael discussed it with me and said, “Do you think I should do this?” and I said, “Yes.” People have asked why he didn’t just pass it up the chain of command, but it’s because nothing would have happened. I’m glad he did what he did.’

Major Stourton set out his motives and concerns in a letter to Colonel Oliver Lindsay, author of Once A Grenadier, the official history of the Grenadier Guards, writing: ‘I felt a duty to my platoon commander and certain other ranks in his platoon to take action.

‘This young officer [Lt Eykyn] was a person of total integrity: a first class leader. He told me that men of his platoon were outraged. They were tough, disciplined and well-trained guardsmen. They had no wish to be associated with these activities that they had both seen and heard. He believed the torture had been carried out by members of the British security forces.’

The Governor himself, Sir Hugh, immediately went to the interrogation center to investigate, but it seems that all trace of mistreatment had been removed by the time he arrived. He had been delayed, wrote Major Stourton, by an unexplained road block.

As for other British officials, Major Stourton was met with indifference. According to his letter, the Commanding Officer told him: ‘This is the kind of thing that I am afraid can happen when people of limited education are given almost unlimited power over people’.

Both Major Stourton and Lt Eykyn were interviewed by Special Branch, but to little purpose. According to Mr Eykyn, the investigators were hostile, while Major Stourton wrote: ‘I was left with the impression they were anxious to discover as little as possible’.

As for the death at Kythrea on October 16 1958, no one was convicted. The victim was a Greek-Cypriot called Spiros Hajiyakoumi, and a coroner recorded an open verdict at an inquest.

Reviewing the claims that Hajiyakoumi had attempted to escape while in custody, coroner Christos Ioannides concluded: ‘There is a complete lack of any positive evidence as to what really happened to this man to cause his death’.

Major Stourton was later informed that two officers were court-martialled and dismissed thanks to his whistle-blowing, yet for the rest of his life he remained disturbed by the lack of interest taken by the authorities.

He wrote: ‘The most strange and indeed worrying feature to me of these events is that not one senior officer made any attempt to ask me, or so far as I know any member of my Company, what happened.’

He left the Army shortly afterwards, as he had always intended, but his decision to speak out cast a long shadow.

‘It wasn’t easy for Michael at all,’ says Mr Eykyn, who remained a close friend until Major Stourton’s death. ‘It took real guts to do what he did, which was typical of him. A lot of fellow officers were not supportive of his decision, and he had to suffer various comments.’

Major Stourton’s son, Harry, says: ‘I know that some of his fellow officers took a dim view and snubbed him for his actions, which weighed heavily on him.’

Major Stourton did not tell his four children about the incident until the 1990s, when he learned that Lindsay was writing his history of the Guards and wanted to include it in the book.

Lindsay corresponded with both Stourton and Eykyn, both of whom co-operated in giving him the full details of their experiences.

In one letter to Major Stourton dated August 22, 1991, Lindsay wrote: ‘I have no plans to be the author of an official history which is misleading or untrue on this very important and interesting incident in Cyprus.’ He sent the draft chapter dealing with the incident to both men to check and amend.

However, when the book was published in 1996, there was no mention at all of the Kythrea incident.

‘Oliver apologized to me for the fact it didn’t get into the book,’ says Mr Eykyn. ‘He told me he submitted a proof to the Ministry of Defence and they redacted it, which is a shame. It was covered up, even almost 40 years after it happened.’

Harry says his father was bitterly disappointed by the absence of the incident from the official record. ‘When he found out the book was being written, it was a great weight off his mind,’ he says.

‘It would have been a vindication of his actions, and it was a crushing blow when he found out it had been redacted. I believe he was ostracised, or something close to it, which is not merely hurtful but dangerous. If good men stand idly by, we are all in terrible trouble.’

But today his family are glad that the story and his part in it are finally emerging. Indeed it is included in a new book, “Unsung Heroes”, by Algy Cluff.

Mr Eykyn, too, is also relieved that the truth is being uncovered – for himself, for his late friend and perhaps most of all for the prisoners who were tortured.

He says: ‘Even after all this time, it’s important the record is set straight.’

Source: Polly Dunbar/dailymail

Ask me anything

Explore related questions