Nearly 1,500 years ago, a Byzantine merchant ship swung perilously close to the Sicilian coastline, its heavy stone cargo doing little to help keep it on course. The ship’s crewmen were probably still clinging to the hope that they could reach a safe harbor such as Syracuse, 25 miles to the north, when a wave lifted the vessel’s 100-foot hull and dashed it on a reef, sending as much as 150 tons of stone to the seafloor. The doomed ship was carrying a large assemblage of prefabricated church decorations—columns, capitals, bases, and even an ornate ambo, or pulpit. These stone pieces lay on the seafloor for 14 centuries until a fisherman spotted some in 1959 while hunting for cuttlefish.

(An underwater archaeologist prepares columns to be hoisted off the seabed at the site of a 6th-century Byzantine shipwreck. The vessel was carrying stone architectural elements intended to decorate the nave of a Christian church)

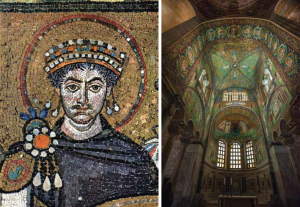

Covering an area a bit smaller than a football field and lying under 25 feet of water nearly a mile offshore of the fishing village of Marzamemi, the site was first studied in the 1960s by Gerhard Kapitän, a pioneering German underwater archaeologist. He believed the Marzamemi shipwreck played an important role in a massive state-led building campaign ordered by Justinian I, the great Byzantine emperor known as the “Last Roman,” whose name is synonymous with a resurgence in the fortunes of the Roman Empire in the Late Antique period.

(Amid the cargo excavated at the shipwreck site is the corner of a stone ambo -left-, or pulpit. Two other sections belonging to the ambo -right- are decorated with Latin crosses)

Based on several design details on the decorations, Kapitän concluded that not only had the ship sunk during Justinian’s reign, but that it had probably taken on its cargo—the decorative elements of a church’s nave—near Constantinople before heading west. He wrote that the marble blocks pointed to “the existence of a large organization clearly directed by a central administration” that dispatched the decorations for a new state-built church. Kapitän felt the Marzamemi marbles constituted “an almost complete set of elements for a Byzantine basilica with the certainty that all the parts are original and of the same period.”

(A mosaic depicting the Byzantine emperor Justinian I -left- decorates Ravenna’s Basilica of San Vitale -right-. The monumental building was one of many constructed during his reign, which lasted from 527 to 565)

Read more HERE

Ask me anything

Explore related questions