If a black hole devours a planet and no one is around to hear it, does it still make a sound? Physicists and astronomers have been trying to map astronomical data through sound for decades—and now we can finally listen to a black hole scream into the void.

Earlier this month, NASA released the first recordings, or sonifications, of what two black holes sound like—and it’s just the kind of noise astronomers and science fiction buffs were expecting: eerie, ethereal, and aurally extraordinary.

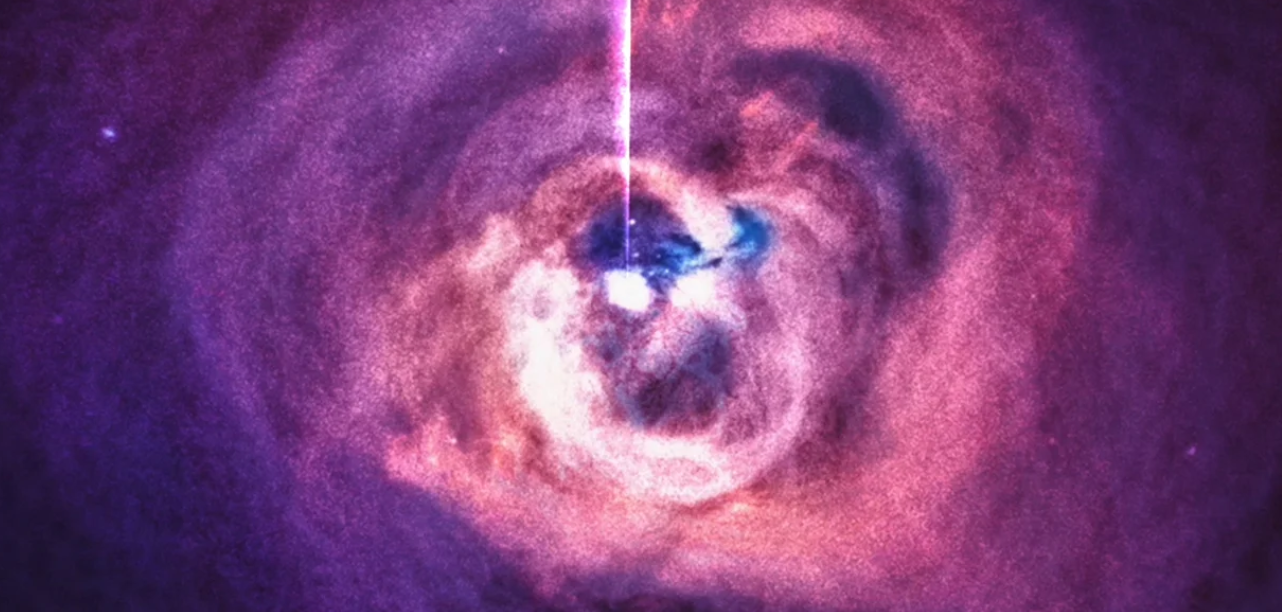

The universe is rife with the hum of celestial melodies—but it’s only relatively recently that humans have developed the technology to be able to hear them. A team of scientists at NASA’s Chandra X-ray Observatory were able to extract and make audible previously identified sound waves from a nearly 20-year-old image of the Perseus galaxy cluster—a collection so full of galaxies, it’s assumed to be one of the most massive objects in the universe. It’s one of the closest clusters to Earth, around 240 light-years away.

NASA says goodbye to Vangelis (video)

“This sort of bespoke method is really about extrapolating something new out of this archival information,” says Kimberly Arcand, the visualization scientist for NASA’s Chandra X-ray Observatory who led the research. Translating scientific data into acoustic signals has also become vastly easier in the past few years. For example, scientists can create parameters for all kinds of numerical data by assigning those values to higher or lower pitches, or vice versa, to turn them into musical notes.

These short sonifications typically take a few hours to create, but with the right data, can be completed using sound engineering software and other publicly available computer programs, like Python.

Read more: popsci

Ask me anything

Explore related questions