The National Intelligence Service (NIS, EYP in Greek) today released declassified information bulletins concerning the tragic events of July and August 1974 in Cyprus, which had previously been confidential classified documents.

These bulletins refer to the invasion of Cyprus and the coup against Archbishop Makarios, both of which were pivotal events in the history of Cyprus and Greece, shaping subsequent Greek-Turkish relations.

This marks the first time that EYP has declassified its archival material, following procedures outlined by relevant legislation.

According to the EYP Director, there is an intention to continue with similar initiatives, offering a chance to consider the agency’s perspective—with its historical context—in studying even particularly sensitive periods of history.

These documents are now available on EYP’s official website, underscoring their historical value and importance, as 50 years have now passed since these events.

The decision to release them aligns with EYP’s policy of transparency and historical documentation of critical events related to national security.

As EYP states: “This essentially serves as a diary of developments from a traumatic period in Hellenism’s history, recorded through the agency’s information at the time, now available for historians and all interested parties to study, extract data, and draw conclusions. Even a simple reading of it, despite the time that has passed, evokes strong emotions and often impresses with its content.”

Professor Evanthis Hatzivassiliou of the University of Athens, in an introductory note offering a preliminary assessment of the material, describes it as crucial, emphasizing that, combined with other available sources, it will contribute to efforts to create a comprehensive picture of those pivotal events.

“On an international level, access for citizens and researchers to similar intelligence agency documents is not always a given. Most countries do not permit this access. Primarily, some Western nations—and not all of them—make their documents public (naturally after a reasonable period defined by law), but even this is a very recent development. For example, the existence of British intelligence services was not officially acknowledged until a few decades ago, which maintained a certain aura of mystery (not always accurate, as it often exaggerated the sense of awe) around their activities. In this regard, EYP’s initiative is an important step toward adapting both the agency itself and the state in general to these international trends, at least within the Western world,” he notes.

See the declassified document from July 1, 1974:

All declassified intelligence releases published by EYP

The entire note by Evanthis Hadjivassiliou

“The decision by the National Intelligence Service (NIS) to make available to researchers the Intelligence Bulletins from the then Central Intelligence Service (CIS) concerning Cyprus and Turkey, covering the period of July and August 1974, marks a milestone in historical research as well as in the documentation of the Service’s own history.

NIS provides valuable material on the 50th anniversary of the Turkish invasion of Cyprus, which can be combined with other evidence to help construct a more complete picture of the events of that summer, which left deep scars on the nation’s course. This initiative, under the leadership of Ambassador Themistoklis Demiris, deserves high praise.

On an international level, citizen and researcher access to similar intelligence documents is not a given. Most countries worldwide do not allow it. Primarily, it is services from Western countries—and not all of them—that release such documents (of course, only after a reasonable period as defined by law). Even this is a recent development. The example of the British intelligence services is well known; for decades, even the existence of these services was not officially acknowledged, which sustained a myth (not always accurate, as it fostered an exaggerated sense of awe) around their activities. In this regard, the NIS initiative is a significant step towards adapting both the Service itself and, more broadly, the state to these international trends, at least within the Western world.

The material being made available is specific. It comprises Intelligence Bulletins about Cyprus and Turkey, which were mainly directed at military services to keep them informed on a daily basis of political developments as well as military movements within Turkey, in areas bordering Greece, and more broadly within the Turkish region and Cyprus.

An observant reader will surely note that this is not the entire body of CIS material for the period in question. In addition to the Intelligence Bulletins, the Service obviously also produced geopolitical analyses, recommendations to government agencies, and of course there were the signals through which information was conveyed within the internal structure. Thus, the material presented today is part of a larger whole. This segment is mainly informational: bulletins that recorded and described developments. Nevertheless, it is material with a coherent structure, offering a comprehensive perspective: these are the Intelligence Bulletins produced during the two months encompassing the Turkish invasion of Cyprus, beginning with the days leading up to Archbishop Makarios’ letter to Phaedon Gizikis, the ‘president of the Republic’ in Athens, and ending after the second Turkish invasion, two weeks after Attila II.

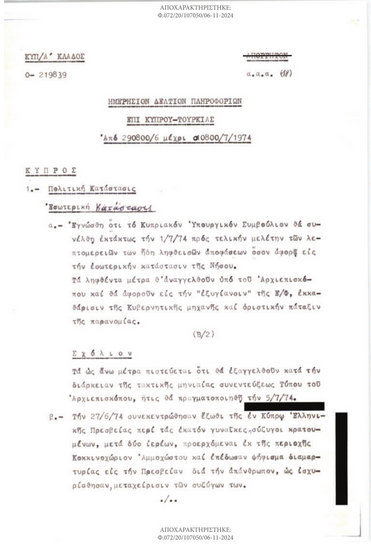

Although the Bulletins are descriptive documents, even in the act of recording and selecting what to report, certain perspectives and analyses are implied, albeit indirectly (and sometimes directly). Based on the material presented, it is possible to draw some observations or hypotheses. In early July, there are numerous and extensive references to various other issues, such as the major issue of the U.S.-Turkish dispute regarding Turkish opium production or Ankara’s (then-new) policy of challenging Greece’s continental shelf. It is a period before the Cyprus crisis, so there is not yet the thematic focus that would emerge in the following days. It is apparent that the Service was not involved in organizing the coup on July 15 against the President of Cyprus, Archbishop Makarios. By their nature, the Intelligence Bulletins would not be expected to contain information on a planned, future coup; they document what happened the previous day, not what has yet to occur. However, from the material, it is rather clear that the Bulletin authors, and generally—this can be said with reasonable certainty—the Service, were not informed about the coup planning. Notably, the Bulletin from July 15 (which covered the period up to 8 a.m. that day) states, ‘It is estimated that the above-mentioned tactics [of Makarios] will continue.’ This mistaken estimate—assuming Makarios’ continued presence—would not have been made if the authors had known that within half an hour a coup would occur against the Archbishop, rendering their assessment incorrect.

From a historical perspective, this lack of apparent CIS involvement in the coup does not surprise me. The Ioannides junta, which knew very well how to carry out coups (though it did not know how to wage war, as was soon, and unfortunately, proven), especially understood the critical need for secrecy and containment of leaks, maintaining the smallest possible circle of informed individuals—only those strictly necessary. It is even unclear whether the highest-ranking officers were informed. The CIS was not within the circle that needed to know about the planning. After the coup, the Bulletins confirm the hypothesis that CIS effectively and accurately reported Turkish preparations for a military confrontation and invasion of Cyprus (see the Bulletins from July 17, 18, and 19), but its warnings were ignored by the regime.

The level of detail in the Service’s reports on Turkish movements and operations, both before and after the Turkish invasion, is impressive. The Bulletins, from the day after the July 15 coup through the aftermath of Attila II, describe Turkish mobilization, the transition of training units to combat status, and unit movements. It is a somber conclusion to realize that Turkey prepared much more effectively than Greece’s ill-conceived and disastrous general mobilization, which led to a collapse of Greek army structures in a single day on July 20. The Intelligence Bulletins ceased for a few days, from 8:00 a.m. on July 19 to 7:00 a.m. on July 23. This should not be surprising, either. At the time the July 20 Bulletin was due—normally right after 8:00 a.m.—the Turkish invasion had already begun, making any information it would contain outdated. Similarly, in the days that followed, military services were updated by the combat-engaged units rather than by the CIS.

The Bulletins resume their regular flow after July 26, becoming much more detailed and extensive. The level of detail in recording both Turkish military movements and ongoing internal conflicts among Greek Cypriots—complicating Glafkos Clerides’ actions as acting President of Cyprus—is striking. This text is not intended to offer a comprehensive analysis of the Bulletins or the stance of CIS. A careful reader of the Bulletins will note some exaggerations, an anti-American and anti-British bias, and perhaps a tendency—also understandable in the tense atmosphere after Attila I—to ‘see’ positive developments (especially in the international climate) where none existed. It is essential to understand what we can find and what it is unrealistic to expect from such documents. For instance, one will not find a detailed ‘history’ of the combat operations: the Bulletins do not extensively describe the battles in Cyprus—this was done by the units and formations involved. More broadly, the CIS documents contain significant and highly interesting records, but they do not tell the whole story, nor should they be expected to.

By offering access to this material, NIS provides sources—documents for study—without adding its own commentary or interpretations, thereby refraining from influencing or pre-determining scientific conclusions. The use of these published documents is up to the interested citizen and researcher, and studying them using scientific methodology will aid in a deeper understanding of the events of those days. This is thus a critically important archival resource that NIS makes available, which, combined with other available sources, will contribute to scientific research and our effort to construct a comprehensive and, ultimately, a definitive picture of those defining events. A scholar like myself finds it obvious to observe that NIS’s decision to make this material available is a very positive step. It would be most welcome if, as the NIS director notes, this initial step is followed by the release of further material for research, and if other state services were to follow suit.”

Ask me anything

Explore related questions