Countless books have been written about Alexander the Great and his myth, yet few focus on the period before his conquests and the unknown, shocking events that followed his death. Examining in detail the various scenarios regarding Alexander’s life and death, Richard A. Billows, in his book Before and After Alexander – The Myth and Legacy (recently published by Patakis Editions, translated by Katerina Servi), offers a calm perspective on the absolute viewpoints. Furthermore, aiming to shed light on the unknown stories of his son’s fate and the battles that followed in Macedonia, with his mother as the central figure, the professor from Columbia University, author, and researcher, explains why the empire Alexander built came to surpass even him. He also reveals details about unknown lovers and mistresses, thoroughly explaining the strategies that helped Alexander win, and sheds light on the conflicts among the successors that, according to the historian, directly influenced the changing narratives concerning his burial.

Billows also uncovers details about the great theft of Alexander’s treasury by a former associate, which tragically resulted in the definitive defeat of the Athenians by the Macedonians and the eventual triumph of the North over the South. However, as the author admits, questioning many aspects of Alexander’s personality, the vast dominance of Alexander and his successors made the Greek element known across the world: “Thanks to the construction of cities by Antigonus, Seleucus, and Ptolemy, Greek urban life and culture prevailed, and the Greek language became universal,” he writes, reflecting on the legacy Alexander left to the Greeks and his successors.

Why Alexander the Great won all his battles – New theories on his death, and where his tomb might be

Richard A. Billows’ Before and After Alexander has just been released in Greek by Patakis Editions.

Why He Always Won

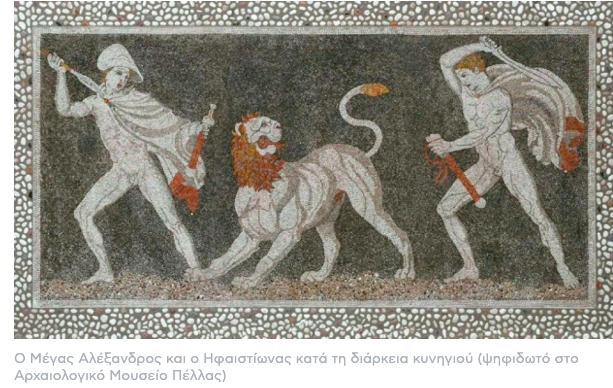

Although Billows is not one of Alexander’s great admirers, he cannot deny the general’s overwhelming success on the battlefield. Naturally, as a big fan of his father Philip, he focuses on the proper training Alexander received from his father and the hunting and military traditions of the Macedonians: “Every Macedonian had to prove his worth by killing a wild boar without a hunting net before being allowed to use a recliner at traditional male dinners, the symposia,” he writes. “By the 4th century BC, deer and wild boars were abundant in Macedonia and were common game; there were also bears, panthers, and lions,” he emphasizes, referring to the iconic depiction of hunting in the royal tombs at Aigai.

However, beyond the tradition of hunting and the martial arts that allowed Alexander to surpass even his father, Billows acknowledges the creativity in battle tactics, suggesting that his victories were largely due to his deep understanding of enemy systems. Among other things, he knew how to defeat the “mahoot” fighters, who preferred to fight not on horseback (a Macedonian specialty) but with elephants. Furthermore, knowing that psychology was key, he spread fear among his enemies by making his accomplishments famous long before a battle. Billows states that the most famous scholars of the time were enlisted to craft stories about Alexander’s feats, with Plutarch himself inventing the tale of the famous meeting between the Great Strategist and the queen of the Amazons in Hyrcania (south of the Caspian). Since the Amazons are mythical, the identification of Alexander with these divine-like warriors was a deliberate way of mixing the divine element with mortal existence. Because it wasn’t enough for him to be king, Alexander understood that by presenting himself as divine, he could symbolically dominate the collective consciousness. He deliberately sought to be seen as a descendant of Hercules and Achilles, which is why he first visited the area of Troy, requesting to be shown the tomb of the legendary demigod.

There, he hurried to offer sacrifices in honor of his supposed ancestor, alongside his companion Hephaestion, evoking clear parallels with the Achilles-Patroclus duo. Since everyone knew Alexander wanted to project himself as a god, they even asked Plutarch if this was his intent, to which he replied, “If Alexander wants to be a god, let him be a god,” possibly because he was the only mortal capable of achieving this. Even today, there are remote areas in Asia where Alexander is revered as a saint. For Billows, an important role in creating Alexander’s myth was played by the widespread image of him throughout the Macedonian Empire via coins, as Apelles, the great painter of the time, was permitted to craft portraits of Alexander as an imposing god holding a thunderbolt (the god of gods).

The Unknown Lovers

Another controversial aspect of Alexander’s personality, which Billows focuses on, is his sexuality. While the possibility that he was strictly heterosexual, as proposed by William Tarn, always existed, Billows believes that bisexuality, which was highly permissible in Ancient Greece, allowed Alexander to engage simultaneously with both sexes, revealing unknown lovers and mistresses. However, as he argues, “One aspect of Alexander’s personality that is strongly documented and beyond dispute is that he was generally not particularly interested in sex. His passions were battle, hunting, and drinking, not sex.” Yet, from an early age, he had an exceptionally close and personal relationship with his beloved friend and companion Hephaestion. Although no source explicitly states that their relationship was sexual, it is highly probable that this was not mentioned because, in 4th-century BC Greek culture, it was considered self-evident, not because it wasn’t the case. In other words, Alexander and Hephaestion were undoubtedly lovers; this is strongly evidenced by Hephaestion’s role as Alexander’s alter ego, a fact supported by many anecdotal stories, and Alexander’s paranoid grief when Hephaestion died in 324 BC. Moreover, we learn that Alexander was passionately sexually attracted to a handsome young Persian eunuch named Bagoas. Alexander’s limited interest in sex seemed to lean more towards homosexuality, but, as with most ancient Greeks, this preference was not exclusive.

He had a duty to marry and produce heirs, and although he neglected this duty for years, he eventually married the Bactrian princess Roxana in 327 BC. Although sources present this marriage as one of love, it was likely a political alliance, much like his father Philip’s marriages. Roxana’s father was a prominent Bactrian noble named Oxyartes, and Alexander needed the support of the Bactrian aristocracy to secure his control over Bactria, which he had conquered with great effort. In 324 BC, Alexander married again, this time two Persian princesses, daughters of Artaxerxes III and Darius III, respectively. However, there was no love involved; the purpose was to connect with the remnants of the Achaemenid royal family. The only indication of genuine sexual interest in a woman was the rumored relationship with Barsine, if there is any truth to it,” concludes the author.

The Theft

Among the many unknown events Billows details is the story of Alexander’s former confidant who stole money from the central treasury in Babylon, where taxes were collected, and fled to Athens with an astonishing sum of 5,000. The amount was supposedly confiscated by the Athenians under the pretext of returning it to Alexander, but they eventually used it to fund their campaign against his successors.

With this money, they mobilized a large army, starting a liberation war against the Macedonians, and even sent the general Leosthenes to Taenarus to pay the former mercenaries of Alexander, whom he had expelled and who had taken refuge there. After Leosthenes gathered them, he convinced several city-states—most notably the Aetolians and Thessalians—to turn against the Macedonian rulers, but they ultimately failed. The initial victory of the Athenians over Antipater, which forced him to fortify himself in Thessaly, ultimately backfired, leading to a coalition of Macedonian generals who decisively crushed democratic Athens in 322 BC, marking its end. In fact, according to Billows, it was this battle, rather than the Battle of Chaeronea, that determined Athens’ fate.

The Tomb Version

Richard A. Billows, believing that Alexander’s relationship with Hephaestion was akin to that of Achilles and Patroclus, argues that Alexander’s grief over his companion’s death led to his own demise. However, there had already been a series of rebellions in the army, which took a severe toll on his psyche, with the most significant being the one at Susa in Opis. Yet, it was in Ecbatana, the ancient Medean capital, where Hephaestion drank himself to death during celebrations, causing extreme sorrow in Alexander, who ordered that Hephaestion be worshipped as a god in some areas. Drinking excessively and mourning his friend for days, Alexander eventually destroyed his already weakened self. When his soldiers saw that death was inevitable, they began to come one by one to bid him farewell.

Perdiccas

It is said that Alexander gave his signet ring to his general Perdiccas, but when Perdiccas asked him whom he was leaving his kingdom to, Alexander replied, “to the strongest.” The Great Strategist took his last breath on June 13, 323 BC, just before turning 33. This was the starting point for a series of conflicts within the Macedonian Empire, which was divided among his officers into zones of absolute control.

This conflict ultimately determined the fate of his tomb, as explained by Billows. Instead of Macedonia, where Alexander wanted it, his coffin remained in Alexandria. The author explains this in detail: “Ptolemy followed an independent policy aiming to make Egypt his kingdom. To achieve this, he emphasized his relationship with Alexander to present himself as the legitimate successor in Egypt: he built Alexandria, the city Alexander had officially founded, though Alexander never saw

Ask me anything

Explore related questions