On Joseph Stalin and some of his criminal actions, primarily before World War II, we have written several articles. We were accused by various individuals of anti-communism; however, we only present documented facts, and we would do the same regardless of who was morally responsible.

Most of our readers seem to agree with us, though some are excessive in their comments. Today, we will focus on yet another inhumane and murderous action of the Stalinist regime: the deportation of 6,700 people to an island on the Ob River in Siberia, at least 4,000 of whom died there over 13 weeks. The most tragic aspect is that many of the individuals who lost their lives fell victim to cannibalism by other deportees on the island. This 1933 event came to light only in 1988, during the years of Mikhail Gorbachev, when the Memorial Organization discovered a related report. This horrific story became widely known in 2002 when Memorial, a human rights organization, released reports from a special commission of the USSR’s Communist Party, dating from September 1933.

Nazino: “Cannibal Island”

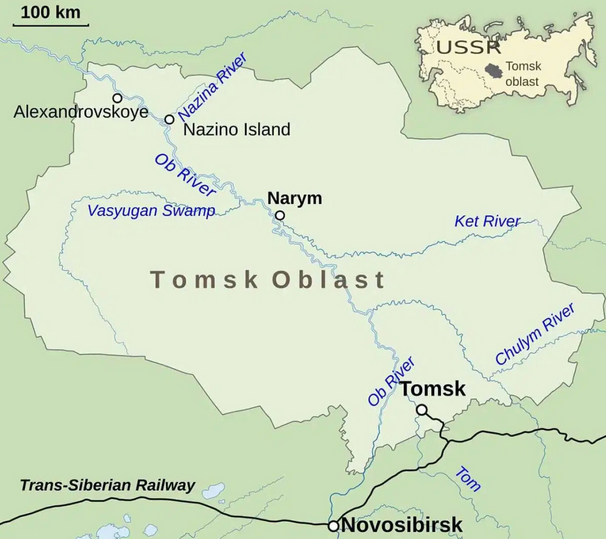

A random internet search on another topic led us to “Cannibal Island.” The title naturally prompts further investigation. To our surprise, we read that “Cannibal Island” is not the title of a book, movie, or game but a raw reality. It refers to Nazino Island, located on the Ob River in Siberia, now also known as the “Island of Death.” As we will see, the nickname “Cannibal Island” is neither fictitious, an invention of Stalin’s opponents, nor an exaggeration, but stems from the fact that some deportees on Nazino fell victim to cannibalism by others.

How was the “settlement” of Nazino Island organized?

In the early 1930s, the Soviet Union sought to spread its population across cultivable lands that had been left untilled across the vast country. An ideal way to achieve this was the relocation of prisoners, who were abundant, as anyone considered an enemy of the regime was imprisoned. Collective farms were to be established in previously uninhabited areas, with prisoners used to cultivate them. In February 1933, OGPU chief Gernikh Yagoda and Matvei Berman, head of the Gulag system, proposed the deportation of two million people to Siberia and parts of Kazakhstan to work on collective farms. This “experiment” had been previously conducted successfully with the kulaks.

Let us briefly explain who the kulaks were, as some might not know. Kulaks (the word comes from the Russian “kulak,” meaning fist) were the upper affluent layer of Russia’s agricultural population. The October Revolution harmed the kulaks by taking away 500 out of the 800 million acres of land they owned. By 1927, despite restrictions, there were still 1 million kulak families, accounting for 4-5% of the USSR’s agricultural population. The final blow to the kulaks came with the complete collectivization of agriculture, which led to their elimination as a class. Some kulaks resisted, with some even revolting and killing state officials. All of these individuals, along with the remaining kulaks, were deported. Despite their hardships under the Stalinist regime, the kulaks fought bravely during World War II (it is estimated that by early 1941, about 930,000 former kulaks remained, some of whom were even decorated for their service). Eventually, after WWII, the last measures restricting the kulaks were abolished, and they were recognized as equal members of Soviet society. (Source: Domi Encyclopedia, 2000).

However, this time, the plan failed miserably. In major cities such as Moscow and Leningrad (St. Petersburg), “internal passports” were issued. This was a reinstated institution from Tsarist Russia, abolished by the Bolsheviks but reintroduced under Stalin with disastrous consequences. The system aimed to identify non-productive, undesirable, and criminal elements for deportation to one of the many gulags in the USSR. The Stalinist regime sought to utilize the most marginalized elements of Soviet society in productive “roles.” However, the “internal passport” system had many flaws, leading to the arrests of even staunch communists and die-hard Stalin supporters who had received “bonuses” for their productivity.

Some examples:

- V. Novozhilov, from Moscow, a bus driver who had received bonuses three times. After work, he was preparing to go to the cinema with his wife. While she was getting dressed, he stepped outside their home to smoke a cigarette without his internal passport (which was inside the house) and was arrested.

- N. Boikuv, a KSM member since 1929 and a worker at the “Red Textile Worker” factory in Serpukhov, was arrested when he went to watch a football match without his internal passport.

- An elderly Soviet citizen over 100 years old was arrested without an internal passport and deported to a gulag.

- Similarly, a young man standing outside his aunt’s house without his internal passport was also arrested.

These are just four examples out of dozens of similar incidents. Between March and July 1933, 85,937 people were arrested and deported from Moscow, and 4,776 from Leningrad.

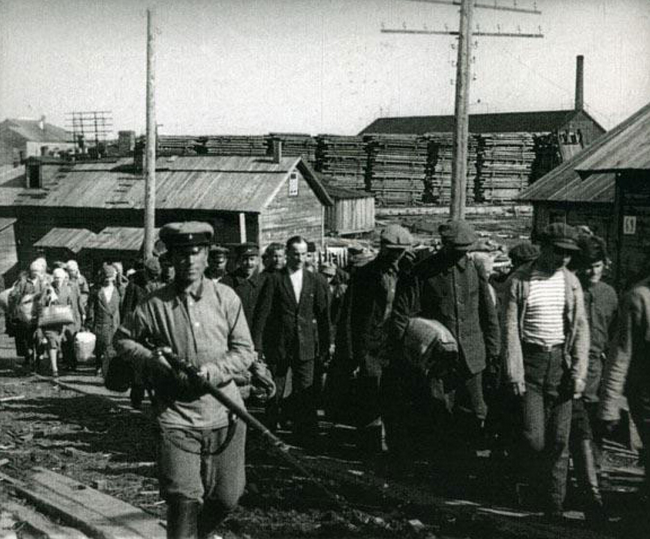

The transfer to Nazino – The inhumane living conditions

Transportation hubs were created in cities such as Tomsk, Omsk, and Achinsk. The largest transit camp, accommodating 15,000 individuals, was established in Tomsk. A train convoy carrying “lower-class” deportees left Moscow on April 30, 1933, while a similar convoy departed from Leningrad a day earlier. Passengers were given a daily ration of 300 grams of bread. Among them were criminals who assaulted law-abiding citizens, stealing their clothes and food.

The authorities of Tomsk were caught off guard by the arrival of all these people and decided to send them to isolated work sites. Two nights after their arrival in Tomsk, riots broke out when some of the deportees dared to ask for drinking water! Mounted soldiers successfully suppressed the uprising. Those destined for Nazino Island spent two weeks crammed into four barges. That’s how long the journey to the island on the Ob River took. The river, 4,016 kilometers long, originates in the northern foothills of the Altai mountain range near the Mongolian border and, following a winding course, empties into the Ob Gulf in the Kara Sea of the Arctic Ocean. On May 5, 5,000 deportees boarded the barges, one-third of whom were criminals. Nazino, located 800 kilometers from Tomsk in Siberia, is sparsely inhabited by the native Ostyak people. The deportees were given 200 grams of bread per day. The barges also carried 20 tons of flour but no other food, cooking utensils, or tools. They were guarded by 50 men under the command of two superiors, who were newly recruited, without uniforms or proper boots.

On the afternoon of May 18, 1933, the deportees disembarked from the barges. Twenty-seven had not survived the conditions during transport and died on board. Nazino Island is 3 kilometers long and 600 meters wide—an incredibly small space for the 322 women and 4,556 men who landed there. One-third of the deportees were unfit for labor.

When the distribution of the 20 tons of flour began, fights erupted among the deportees. The guards started shooting at them. The next day, the distribution was repeated with the same outcome. Consequently, leaders were appointed among the prisoners to handle the distribution, but they hoarded most of the flour for themselves. There were no guards on the island; they remained on boats along the shores. The prisoners ate flour and drank water from the Ob, leading to a rapid spread of dysentery in this peculiar gulag.

As if that weren’t enough, on May 27, another 1,200 deportees arrived on Nazino. Some prisoners constructed primitive rafts to escape the hellish island. Some drowned, others were executed by the guards, and only a few managed to escape.

Gangs and Cannibalism on the “Island of Death” – The Shocking Behavior of the Guards

Predictably, the situation spiraled out of control. Most of the deportees on Nazino were city dwellers with no knowledge of farming. The scarcity of resources led to the formation of gangs that easily overpowered the weaker individuals. People were murdered over disputes involving money or food. Gold tooth fillings and crowns were removed by gang members and used to barter for food and cigarettes. The three doctors sent to Nazino to assist and protect the deportees soon feared for their own lives. The lack of food and the rising death toll by late May led to acts of cannibalism. Some prisoners murdered others to eat them. On May 21, the three doctors recorded 70 new deaths, and evidence of cannibalism was observed in five cases. By June, guards had arrested 50 individuals for cannibalism. Victims were skewered and roasted over fires.

One surviving cannibal recounted that he ate only livers and hearts. The skewers were made from willow branches, and the cannibals targeted those who had only two or three days left to live. The same cannibal explained: “It was obvious they were going to die—within a day or two, they’d give up. So it was easier this way, quick. No more suffering for another couple of days.” For obvious reasons, we are only sharing parts of the cannibal’s account to illustrate the incredible crimes and unprecedented actions some “humans” are capable of. Of course, the guards were not blameless either. They threw pieces of bread to the starving prisoners and laughed as they fought over them. From the safety of their boats, they drank, got drunk, and then shot at prisoners for fun or target practice. They traded cigarettes and bread for “favors” from the women on Nazino. The guards only acted when cannibalism became evident, but by then, it was too late to prevent the atrocities.

The End of the Ordeal

This nightmarish situation ended in early June 1933, when Soviet authorities disbanded the settlement on Nazino. Of the roughly 6,700 people initially sent there, 2,856 survivors were moved to the banks of the Nazina River, a tributary of the Ob. Another 157 who were too weak to move remained on the island. During their relocation to the Ob’s shores, many died. The remaining deportees faced new challenges, especially typhus. Of those originally sent to Nazino, only 250 were eventually fit to work. In the Tomsk region, new deportee settlements were built, but as we will see later, they were not utilized.

Vassily Arsenievich Velichko’s Investigation

Vassily Arsenievich Velichko, a local Communist Party leader in the Narymsky district of Western Siberia, began hearing rumors about the events on Nazino. Without approval from his superiors, he rushed to investigate. When he arrived at the island in August 1933, he was confronted with a horrifying scene—half-eaten corpses hidden among the tall grass. He spoke with many nearby Ostyak residents and pieced together what had happened. His report was sent to Moscow. His “reward” was expulsion from the Communist Party and dismissal from his job.

Cover-Up and the End of the Resettlement Plan

Velichko’s report was addressed to Stalin but ultimately reached Lazar Kaganovich, Stalin’s close associate. It was distributed among Politburo members and archived in Novosibirsk. The only ones punished were the guards and their commanders, who received prison sentences ranging from 12 months to three years. However, the horrific events on Nazino marked the end of the ambitious plan to colonize barren and uncultivated areas. Tragically, Nazino was not the only site of such incidents. In 1933 alone, there were 367,457 forced relocations to various settlements. Of these, 215,856 disappeared (?) from the settlements…

Did Stalin Know About the “Relocations” Plan?

Officially, the implementation of the “relocations” plan by Yagoda and Berman began on their own initiative, without Stalin’s approval at first. According to thecollector.com, Stalin rather quickly rejected the plan for the gulag at Nazino. This occurred before the transfer of an additional 1,200 displaced persons to the island. The justification given for this transfer was attributed to a “bureaucratic error.” Knowing the general workings of the Stalinist regime, it seems unlikely that Yagoda and Berman acted independently. Moreover, they faced no punishment whatsoever after the resettlement program ended.

Yagoda was later arrested, tried during the Trial of the Twenty-One in March 1938, found guilty, and swiftly executed after the trial. In 1988, twenty of the twenty-one individuals tried in 1938 were rehabilitated, as it was acknowledged that the entire trial was based on false confessions. The only one not rehabilitated was Yagoda.

In contrast, Berman was arrested in December 1938 after being expelled from the Communist Party and imprisoned in the Lubyanka. He was found guilty by the Military Collegium of the USSR Supreme Court, accused of being a member of a terrorist organization, and executed on March 7, 1939. However, he was rehabilitated on October 17, 1957. Despite the risk of being accused once again of anti-communist bias, it appears that Stalin approved everything but did not anticipate the dramatic events that would ensue. He distanced himself by shifting the blame onto others. If Yagoda and Berman had acted on their own initiative, they would likely have been summarily executed in 1933.

The Revelation of the Atrocities

For 55 years, what happened on the “Island of Cannibals” remained unknown to the general public. Only in 1988, under the framework of glasnost (openness) introduced by Mikhail Gorbachev, were the details of the case revealed to the public through the Human Rights Organization Memorial.

An Ostyak who lived during that time told Memorial representatives that those who escaped and encountered the Ostyaks asked them, “Where is the railroad?” and “How can we get to Moscow or Leningrad?” The Ostyaks had never seen a railroad and were unaware of the names “Moscow” and “Leningrad”! In 2002, Memorial uncovered even more information.

In 2006, French historian Nicolas Werth, known for his book The Black Book of Communism, wrote Cannibal Island about the Nazino affair. The book was translated into English in 2007. In 2009, the documentary L’île aux Cannibales (The Island of Cannibals) was produced based on Werth’s book. In 2011, the TV film Cannibal Island, directed by Cedric Cordon, was released, starring Fabrice Pierre, Natalia Dufraisse, Andrei Zayats, Anton Yakovlev, and others.

Sources: Wikipedia

The Collector: “What Happened on Nazino Island? The Cannibal Gulag,” 6/8/2023

There are numerous other references to this topic online (search “Cannibal Island Nazino”), which has even been turned into a computer and mobile game.