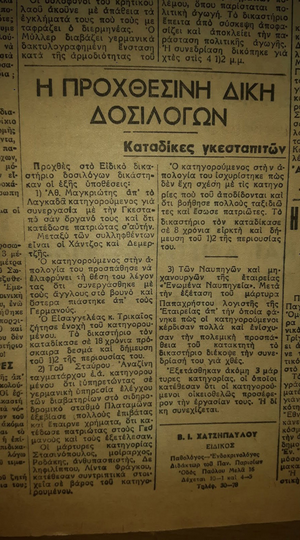

We continue today our report on the collaborators of the Occupation, with Part B. As for the names of the “collaborators,” this is a very sensitive issue. Both M. Charalampidis and D. Kousouris, whose rare book “Trials of the Collaborators” we found in the days since the previous article, often rely on initials.

Illegal Logging: a Profitable Activity during the Occupation

According to Menelaos Charalampidis, an especially profitable enterprise (and probably unknown to many…) was the procurement of huge quantities of timber, mostly resulting from illegal logging. The timber was necessary for the occupying forces for fortification works, military shelters, shipbuilding, and fuel. The Germans granted permits for logging directly, without competition, to Greek contractors – suppliers. Post-war, there were at least 30 trials for illegal logging in the Special Courts for Collaborators. As Apostolos Doxiadis writes in his book “The Sacrifices of Greece in the Second World War,” Athens 1946, 75% of the forests in Attica were destroyed due to illegal logging during the Occupation. In one of the trials, the forest ranger Georgios Triantafyllidis referred to the attempt by employees of the Ministry of Agriculture to prevent the destruction of a forest in Pikermi by the merchant Alkiviadis Koronaio, who supplied the German navy with shipbuilding timber. Koronaio threatened the conscientious forest ranger that he would report him to the Germans for sabotage. As the ranger stated, this group “logged shipbuilding and mining timber amounting to about 3,000 cubic meters and 1,000,000 firewood.” However, it was not only Pikermi where this specific group operated: Nea Erythrea, the Monastery of Penteli, Stamata, Spata, Boyati (Agios Stefanos), Kalentzi, Marathon, Voula, Vouliagmeni, Glyfada, Kavouri, Varkiza, and others were some more areas. In court, three of the seven accused appeared. But two had been killed during the December events. Of the two present accused, one was acquitted, and the other was sentenced to four years in prison. One of the accused, Haralambos Pezas, an industrialist, while awaiting trial, was found fighting alongside gendarmerie officers against the ELAS during the December events, defending the General Security building on Stournari Street. He was injured in battle and succumbed to his wounds on January 19, 1945, at the Red Cross. Another accused, the merchant Grigorios Baltas, was killed in Peristeri during the December events.

The Food Supplier with 18 Properties!

Another heterogeneous business group, consisting of a distiller, two merchants, a chemist, a public servant, and an order clerk, was tried post-war for economic collaboration with the Germans. The distiller Panagiotis Lazaridis, realizing the great needs of the Nazi army fighting under harsh conditions in the African desert, took it upon himself to supply these troops with mineral water and soda that reached Rommel’s troops in North Africa via Libya. Soon, the collaboration with the Germans expanded to other products: margarine, soap, and fats, which the group made using large quantities of oil provided by the Germans. Since it was impossible to produce all these products by themselves, they created a network of collaborators and managed to produce them in third-party factories, always for the Germans: they made margarine at the Papadopoulos biscuit factory, soap at the Papoutsanis factory, and other products at the ELAIS factory. The paradox is that several “witnesses of the prosecution,” employees and colleagues of the accused, claimed that Lazaridis was harmed by his collaboration with the Germans. However, this is probably not true, as during the Occupation, he bought 14 properties in Kallithea and another 4 in Kolonaki, Psiri, and Ambelokipi. The total price for these was 781.6 golden pounds. The Special Court for Collaborators was extremely lenient with Lazaridis, as he was sentenced to only ten months in prison.

Athanasios Vasiliadis: The Biggest “Investor” in Real Estate During the Occupation

While Lazaridis’ real estate investments are impressive, they pale in comparison to those of Athanasios Vasiliadis, who, in a publication of the Journalists’ Union of Athens (archive of Heraklis Petimezas, box 40, “The Plutocratic Oligarchy on the Side of the Occupier,” Athens 1943, p. 20, illegal publication of the EAM), is featured as the first on the list of the “greatest beneficiaries of Hitlerian fascism,” as “from a low-ranking employee at Siemens (sic), he is now with bags of gold and pouches of diamonds.” But who was Athanasios Vasiliadis? As M. Charalampidis writes, he bought the same number of properties as Lazaridis (18), but at four times their value, as his purchases were in areas like Kolonaki and the northern suburbs. Vasiliadis was a simple employee of A.E.G. However, he soon became an entrepreneur supplying the German army with electrical goods (refrigerators, stoves, heaters, lamps, etc.). He quickly resigned from A.E.G. and opened his own electrical goods store on Voukourestiou Street in Kolonaki. Let’s look at the properties he bought: a 850 m² house in Chalandri, a 401 m² house on Thiras Street in Amerikis Square, a 349 m² house on M. Asia Street in Ilisia, two houses totaling 1,796 m² on Levidi Street in Kifisia, a 769 m² plot on Poseidonos Avenue in Paleo Faliro, a house and plot totaling 6 acres in Peuki. Many of his purchases were also in Kolonaki: two apartments of 245 m² and 144 m² on Dimokritou Street, two houses of 205 m² and 114 m² on Anagnostopoulou Street, a 371 m² apartment on Sina Street, and two houses of 422 m² and 417 m² at the intersection of Voukourestiou and Solonos Streets. In February 1948, his trial took place in Athens. Vasiliadis did not appear in court. He was convicted in absentia to 5.5 years of imprisonment. His fate after the war is unknown… During his trial, witnesses appeared who spoke about his philanthropic work, as well as the help he provided to his fellow citizens in Marousi, either by giving them money or by intervening with the Germans when there were problems with some of them…

The Sakelloropoulos Couple: Two More Philanthropists of the Occupation

Christos Sakelloropoulos and his wife, Charlotte Werner-Sakelloropoulou, were two more philanthropists of the Occupation. Christos Sakelloropoulos was a lawyer and director of the construction company “Cyclops.” He was very active in the construction sector but also contributed to the requisitioning for the benefit of other businesses. His co-defendant was his German wife, Charlotte Werner-Sakelloropoulou. The indictment for the couple was voluminous and very serious. However, they presented to the investigator of the case a series of documents that certified their social sensitivity.

A letter from the Board of Directors of the Popular Neighborhood Committee of Saint Paul in Vathis thanked Charlotte Werner-Sakelloropoulou for the “constant moral and material support” she provided to the poor and sick children of the neighborhood. The Bomb Victims Welfare Committee of Piraeus thanked the company “Cyclops” for donating a golden pound in September 1944. The Piraeus Bar Association expressed its gratitude for the donation of 20 million drachmas for needy lawyers, and the Panhellenic Union of Merchant Navy Engineers thanked the donation of 40 million drachmas for the needy engineers. Notably, all of these donations were made just before the end of the Occupation. Obviously, all this philanthropic action played its part in the acquittal of the couple, despite the heavy indictment against them…

Machine Shops – Shipyards during the Occupation

Immediately after the military occupation of the country, primarily German, but also Italian, companies took on the task of securing Greek industrial and craft production for their benefit. This was mostly done through requisitions and the signing of long-term contracts that bound the production for German and Italian companies. The Germans were particularly interested in minerals, tobacco production, and the small Greek military industry. Thus, by the end of May 1941, at least 38 Greek leather processing and textile companies were fulfilling orders for the German army for: blankets, sheets, fur coats and jackets for the Eastern front, summer uniforms and footwear for the German soldiers in Greece, and finally, tents and mosquito nets for the Germans in North Africa. The eleven largest Greek tobacco companies jointly submitted a bid to the Nazis to produce 2,800,000 cigarette packs per day for the German army. The necessary and cheap raw material came from the 40,000 tons of unprocessed tobacco that the Germans had “requisitioned.” Some of these tobacco companies still operate today…

Although one might expect the opposite, during the years of the Occupation, at least 5,700 new businesses were founded in the country! The sector where massive requisitions occurred and saw significant growth, due to the guaranteed work for the occupier, was the mechanical workshops and shipyards. One of the mechanical workshops that grew during the Occupation was that of Stylianos Savvas and Efstathios Chabakis. Before the war, the workshop employed 40 workers. Immediately after its requisition by the Germans in November 1941, the number of workers rose to 340! As production declined in the following years, this had an impact on the number of employees, which was 225 in 1943 and 100 in 1944. There were complaints about this specific workshop, stating that the management pressured and terrorized the workers, even going so far as to call German soldiers to the workshop as a means of intimidating the staff! Additionally, part of the food rations provided to the workshop by the Germans for the workers’ meals was withheld by the management! The owners of the workshop were tried after the war and were acquitted!

The largest metallurgy company of the time was that of Dimitrios and Alexandros Staurianou, based in Keratsini. The factory was requisitioned by the Nazis in 1941. The management had managed to receive rations from three “sources” (German Navy, German Air Force, and the Red Cross), which was prohibited. Only part of this food reached the workers, as the rest was channeled by the owners to the black market. One of the owners was arrested and imprisoned in 1942 for stealing quantities of iron meant for the production process and also selling them on the black market! In addition to the above, the lawsuit that reached the hands of the Commissioner of the Special Court of Piraeus contained accusations of making large profits from contracts with the Germans and of denouncing workers to the SS. Worker mobilizations from the labor EAM for better rations led to them being targeted in the workshop, resulting in a slowdown of production, much of which was meant for the construction of cement ships by the German navy, and led to the workshop being surrounded by the SS. A German officer went to the company’s offices, and after speaking with the owners and managerial staff, he went down with them to the hall. The staff from the molding department was asked to gather there. Fourteen workers, whose names were read aloud, were arrested by the SS and taken for interrogation to the infamous building on Merlin Street in Kolonaki.

They were referred to trial at a German military court, accused of sabotage and distributing communist leaflets. On August 28, 1943, following the court’s decision, they stood before the German execution squad at the Kaisariani shooting range: Giorgos Zambounis, 19 years old, fitter, Dimitris Gyparis, 26 years old, mechanic, Panagiotis Lourbeas, 34 years old, foreman, and Giorgos Polymenakos, 33 years old, foreman. They were all members of the labor EAM, residents of Piraeus, and worked at the Staurianou factory. Seven other workers were sent to Germany for forced labor, and no one ever heard from them again… After the executions of the four, the company’s legal advisor visited their families and, along with the condolences, conveyed the intention of the owners to offer a monetary amount, along with a property to each family, as long as, as stated in the sworn testimony of Polymenakos’ brother, Athanasios, on 20/11/1944, “I sign that the Staurianou brothers are not responsible for the executions of my brother and the other three.” However, all the families refused this “offer.” After the liberation, the relatives of the victims filed a lawsuit against the owners and managerial staff of the company. However, the company owners also filed a lawsuit against the general manager! After reviewing the lawsuits, witness testimonies, and the mutual accusations between the owners and managerial staff, the Commissioner proposed to the judicial council that the accused not be referred to trial due to insufficient evidence to establish a charge. Responsibility for the denunciation of the 14 workers was attributed to only one person: a foreman of the factory who had already been executed by OPLA.

Even here, it seems that the judicial authorities “forgot” (?) to examine the significant purchases of the company owners between September 1941 and October 1942: land totaling at least 169 acres in Adames, Kifisia, a property of 610 m² on Polignotou Street in Monastiraki, and, possibly, a house of 415 m² in Nea Smyrni, another 119 m² in Attiki Square, and another 152 m² in Plaka. Additionally, the general manager of the company purchased a house in Patissia, two plots totaling 846 m² in the “Petra” area of Palaio Faliro, and a vineyard with a farmstead, covering 8 acres, in Elliniko (then Hasani).

The Great Trial of the Entrepreneurs (October 1948)

In October 1948, a major trial for economic collaboration with the occupiers took place at the Special Court of Piraeus. The accused were 23 entrepreneurs, almost all the owners of the Perama shipyards that had been requisitioned by the Nazis. In addition to the shipbuilding sector, many of the 23 had also been involved in the operation of gambling clubs and casinos! At the Special Court, 13 witnesses for the prosecution and 49 defense witnesses appeared. However, the prosecution witnesses also “functioned” as defense witnesses. Almost all of them said that the Germans requisitioned the businesses of the accused, that they were forced to sign contracts with the Nazis due to the requisition, that they delayed deliveries as much as they could, and that they provided full meals for the workers, whom they never pressured to increase production. Although among the prosecution witnesses, there were directors of banks where the accused had accounts, no one responded to whether they gained profits from their collaboration with the Nazis. Here too, the judges “forgot” to examine the fact that three of the accused, the brothers Dimitrios, Asimakis, and Efstratios Vombas, bought during the occupation a 161 square meter house in Kypseli, two plots of land of one acre in Kolonos, a 183 square meter house in Platia Attikis, and three villas of 765 square meters, 1,250 square meters, and 2,330 square meters in Psychiko! Another accused, Lazaros Rozakis, as reported in the newspapers, had bought an entire apartment building on Skoufa Street in Kolonaki and possibly a house in Exarchia and a farm of 8.5 acres in Stavros Agias Paraskevis. Finally, George K. (no surname provided by M. Charalambidis), a shareholder of the company, who was not referred to trial, bought 12 properties during the occupation in his wife’s name!

The defense witnesses were prominent people, due to their positions in the state apparatus: senior officers of the City Police and Gendarmerie, a former MP, shipowners, merchants, industrialists, curators, lawyers, customs officers, doctors, a high school principal, notaries, shipyard owners, and a archimandrite, who testified in favor of the Vombas brothers, whom he met after their settlement in Psychiko.

“They came as benefactors with large sums of money to charitable foundations,” said the archimandrite, who described the Vombas brothers as “Christian and respectable Greeks,” adding that “I never noticed a lack of national dignity in them”… As for the hundreds of workers at the shipyards and machine shops? Only two appeared to testify at the Special Court. Logically, their “voices were lost” among the 62 total witnesses. As a result, 27 of the 28 defendants were acquitted and only one was sentenced to 10 months in prison…

The Black Market and the “Occupation Expenses”

The illegal (black) market resulted in many Greek entrepreneurs amassing huge fortunes during the occupation. Access to this market was achieved in two ways: either through connections with German and Italian officials in Greece, or with the access to goods in high demand by entrepreneurs working for the occupiers. On December 15, 1942, in “The Fighting Greece,” the following was written: “Whatever is offered today in the market is the product of concealment by Greek merchants or of hoarding – through the system of requisitions by German or Italian officers and entrepreneurs… the Axis army has this characteristic, that behind every officer is an entrepreneur who, knowing that his country has lost the game, tries to enrich himself at least and secure a comfortable future after the defeat. For this reason, the wholesale black market was organized and managed by Germans and Italians.” In the second case, the occupiers supplied requisitioned businesses working for them with food, which was distributed to the workers in the form of rations, as well as with the necessary raw materials for the production process. All of these goods were sold at astronomical prices on the black market. One of the most common practices of the owners of requisitioned businesses was stealing raw materials, portions of the workers’ rations, and diverting quantities of the final product and selling them at exorbitant prices on the black market, which is estimated to have represented 40% of the economy during the occupation. Hundreds of thousands of families were forced to sell their properties and other assets at incredibly low prices to the black marketeers. Moreover, the money they received was usually spent on buying goods that were sold on the black market! Thus, wealth was concentrated in very few hands! A significant portion of the occupation expenses spent by the Germans in 1944, specifically 51.2%, ended up in the hands of those undertaking infrastructure works. Another 25.1% went to food merchants. Finally, part of the wages of German soldiers (6.8%), as well as operational expenses (10.5%) also ended up in Greek hands, as the soldiers spent their wages in Greece, and the expenses for medical supplies and machinery maintenance also ended up in Greek hands.

Real estate market: The “safe investment” during the Occupation – The incredibly large number of properties that changed hands

Most of the money that some individuals unlawfully acquired ended up in the real estate market. This began just three weeks after the Germans entered Athens, starting from mid-May 1941. From November 1941 to the end of 1942, the real estate market experienced a real boom, something that can be seen from the columns of the “Oikonomikos Tachydromos” and “Oikonomologos Athinon,” where property transactions in the capital were recorded. According to data collected by the Panhellenic Federation of Real Estate Sellers during the Occupation, which was formed in late 1945, between 1941 and 1944, at least 350,000 properties were sold across the country (110,000 urban, 239,000 rural, and 1,000 industrial). 74% of the real estate transactions took place between May 1941 and December 1942. These properties were sold at very low prices. Specifically, the 350,000 properties had a pre-war value of 90,000,000 gold pounds and were sold for 6,000,000 gold pounds, which is 7% of their original value! Nationwide, 1,500 people bought between 11 and 20 properties each, 400 people bought between 21 and 50 properties each, and 100 people bought more than 51 properties each! (ELIA – MIET, archive of the Panhellenic Federation of Real Estate Sellers during the Occupation, “Consolidated Table of Statistical Data on Sales 1941-1944”). The majority and highest-value sales occurred in the then sparsely populated areas of Platia Attikis, Platia Amerikis, Ano and Kato Kypseli (2,384 properties, of which 1,302 were houses), 928 plots of land, 98 apartments, and 56 unspecified properties. In the also sparsely populated area of Glyfada, at least 427 plots, 94 houses, and 68 rural estates and farmlands with a total area of at least 567 acres were sold. In Kifisia, 214 plots, 122 houses, and 101 farms and properties, with a total area of 2,000 acres, were sold. From the sale of the 350,000 properties, the Panhellenic Federation of Real Estate Sellers during the Occupation estimated that approximately 1.5 million people were affected. By the end of the war, those who survived were destitute, in contrast to others who acquired immense wealth during the difficult years of the Occupation…

The lenient sentences of the Special Courts – A case of vigilante justice in Crete

As mentioned in the previous article, many cases of collaborators never reached the courts. Even those that did were generally met with leniency. Dimitris Kousouris, in his book “Trials of Collaborators (1944-1949),” provides the professional profiles of the accused in the Special Court of Athens, based on a sample of 15% of the total. According to this sample: 49% of the accused were workers, private employees, small traders, and peasants. 29% were public employees (politicians and military), 15% were professionals (lawyers, doctors, and engineers), and 7% were industrialists and businessmen. From 1945 to 1949, in the Special Court for Collaborators in Athens, 114 individuals (5.2%) were sentenced to death, 121 (5.5%) to life imprisonment, 191 (8.7%) to sentences of 10-20 years, 103 (4.7%) to imprisonment for 5-10 years, 173 (7.8%) to imprisonment for 1-5 years, 147 (6.7%) to imprisonment for less than 1 year, while 1,356 (61.5%) were acquitted! Because of this, the Special Courts for Collaborators were denounced as “acquittal courts”… Greece displayed one of the lowest rates of collaborator convictions per 100,000 population. Specifically, the conviction rates per 100,000 were: in France 90, in Greece about 95, in Austria 203, in Hungary 270, in Denmark 333, in the Netherlands 553, in Norway 573, and in Belgium 582. In our country, there were also cases where citizens found the decisions of the Special Courts provocatively lenient and took the law into their own hands. One such case mentioned by D. Kousouris occurred in Crete. The Special Court in Heraklion was overly lenient towards 5 informers responsible for 31 executions during German reprisals in the mountain village of Sarchos, Heraklion. Its decision “…provoked the reaction of the relatives of the victims and the large audience, which numbered more than two thousand people and gathered outside the court. The local police force, reinforced by soldiers, tried to control the crowd, and measures were taken to protect the lives of the convicted individuals, who were locked in the first interrogation room. However, the enraged crowd broke through the police force, which numbered 30 men, and entered the court, smashed the door of the first interrogation room, and butchered all the convicted individuals, whose bodies were thrown into the street.”

These were two women and three teenagers from the Somaraki family, who had been informing the Nazis about their fellow villagers who supported the resistance. One woman was sentenced to death, while the other received a life sentence. Two of the three teenagers were sentenced to 3-4 years in prison, while the third was acquitted. In the end, all of them were killed by the angry crowd. Initial reports mentioned that 7 police officers were killed, but this was not confirmed.

And let us not forget that on May 23, 1945, the Special Court for Collaborators in Ioannina, with its decision no. 344, sentenced in absentia 1,930 Chams to death, who were accused of war crimes during the German Occupation…

Sources: Menelaos Charalampidis, “THE COLLABORATORS,” 5th Edition, Alexandria Publishing, April 2024.

Dimitris Kousouris, “TRIALS OF THE COLLABORATORS,” Polis Historia Publishing, reprint, March 2021.

Ask me anything

Explore related questions