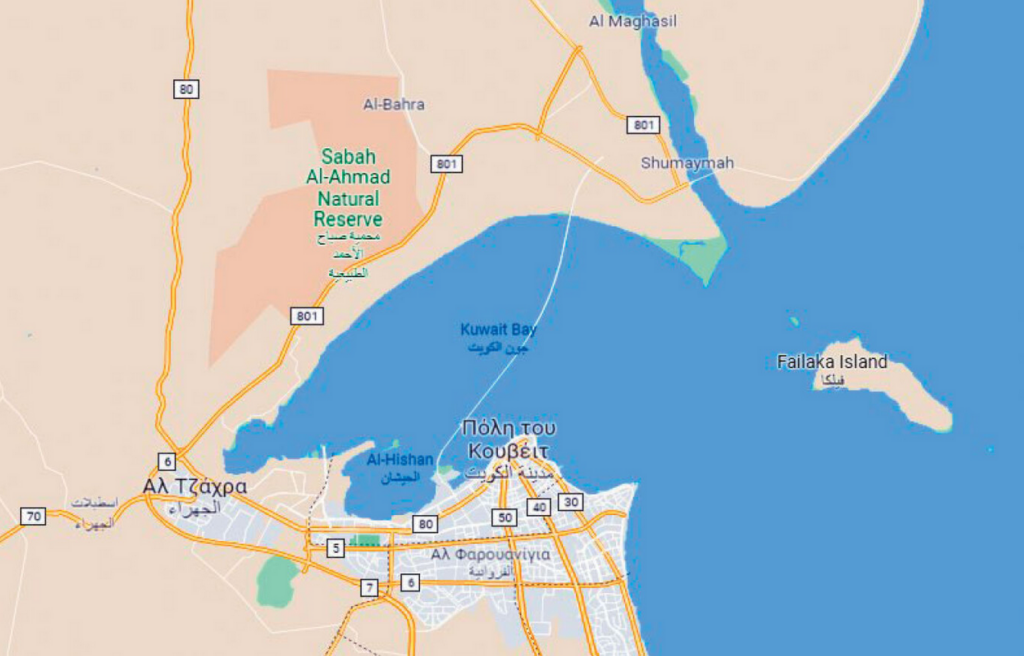

The name Icarus dominates everywhere on this distant little island of Failaka, at the edge of the Persian Gulf, which is now revealing treasures related to the rule of Alexander the Great and the prevalence of the Macedonian element in the region. There, on the beautiful island that today belongs to the emirate of Kuwait, a Greek colony was founded during Alexander‘s campaign in the 4th century BC, directly linked to the great conqueror, serving as a piece of memory for him and his generals. The latest discoveries now coming to light at the site of Al-Quainiya—including an entire building, a courtyard, and numerous ceramics—demonstrate the Hellenistic presence in other parts of the island as well and confirm the significance of this small place during the Hellenistic period.

It all began during Alexander the Great’s return from the Indus River when he realized the necessity of sea access from the vast Arabian Peninsula. That is why he sent his general, Nearchus, to explore the coastal regions and find an ideal location that could serve as a maritime gateway to the Persian Gulf and the mouths of the Tigris and Euphrates rivers. Nearchus led an entire Macedonian fleet, whose men endured various hardships as they wandered through unfamiliar lands, beginning from the Hydaspes River and sailing toward the Persian shores.

After days of adventures in unknown waters with no food, surviving only on palm fruits and believing they were being pursued by evil spirits, they arrived at the uncharted island. To ease their fears and overcome their superstitions, Nearchus decided to set foot on the island first, encouraging all the ships that had gathered from different parts of the Mediterranean—from the Aegean islands to the Hellespont. On the shores of the Persian Gulf, he discovered this particular island, a small earthly paradise in an extremely strategic location at the confluence of the Tigris and Euphrates—an especially critical position, as it controlled the route to Babylon.

As Arrian, the historian who provides information about Alexander’s island, notes, Icarus was lush and green, with a small forest full of various birds, deer, and flowing waters. It was understandably protected by a female deity, whom the locals then called Mother Goddess, similar to the prehistoric Potnia Theron depicted in the frescoes of Akrotiri in Santorini. Though young women may not have flocked to her with loose hair and saffron crocuses, as in Minoan rituals, they did sacrifice wild goats found on the island—though they did not eat them.

The Macedonians took care to transform the worship of this female deity into a temple dedicated to Artemis, incorporating into its construction all the cultural influences that shaped the region. Indicative of this are the Ionic columns with Persian-style bases, reflecting the harmonious blending of civilizations that Alexander the Great championed until the end. This fusion of Greek and Persian culture highlights the conqueror’s effort to integrate elements of foreign traditions rather than forcibly impose Greek Macedonian customs and religious practices.

As for the name Icarus, it is said to have originated because the island resembles Ikaria—or at least something along those lines, as noted by great geographers like Strabo. However, over time, the name by which it became widely known prevailed: Failaka, which was adopted by the Arabs and remains in use to this day. Many scholars, including archaeologist Angeliki Kottaridi, insist on tracing Greek roots in the name, suggesting that “Failaka” derives from the Greek word “φυλάκιον” (phylakion), meaning “outpost,” referring to the garrison that Alexander the Great established in the area.

This conclusion is supported not only by the temple discovered in 1958 by Danish archaeologists—who recognized the significance of this remote island—but also by a series of subsequent findings. These include coins, inscriptions, figurines depicting Artemis, and pottery, all of which reveal the Greek Macedonian character of the region. Roman sources also helped identify the island as a place of great importance, describing Icarus as a wealthy Greek city that, in addition to the renowned temple of Artemis Tauropolos, also had a temple of Apollo—these two sanctuaries were typically found together—as well as a highly significant oracle.

Excavations that unearthed valuable evidence of the island’s Hellenistic identity halted for years but resumed after the Gulf War in 1991, led by Polish, American, and Greek teams. The Greek mission, with the significant contribution of Angeliki Kottaridi, played a crucial role in archaeological research and in preserving the famous “Stele of Icarus,” which contains 43 lines of Greek inscriptions. Excavations continued intensively from 2014 to 2020, uncovering various structures, mainly residential buildings from the 8th century AD, during the early Islamic period. Now, once again, new discoveries are shedding light on the island’s vibrant presence during the Hellenistic era.

How the Stele of Icarus Was Saved

The archaeological excavations carried out in the area in 2008, with the contribution of archaeologist Angeliki Kottaridi—an expert on the history of the Macedonians and the mastermind behind the restoration of Aigai—revealed architectural similarities between the structures on the island and those built by the Macedonians. Kottaridi, specializing in Macedonian architecture, identified parallels not only with those of Ancient Pella but also with other findings, such as pottery.

She was the one who managed to restore the fragmented Stele of Icarus, which bears a Greek inscription. It is deeply moving to think that a woman from Macedonia, retracing the steps of Alexander the Great, was able to reassemble and reinstall the shattered stele in its original base after 2,000 years, deciphering the messages it conveyed. For many years, before Kottaridi took the initiative to restore it, the stele remained broken into many pieces, stored in a crate, with no one paying attention to its preservation.

Yet, the Stele of Icarus was crucial in identifying the island’s connection to the Macedonians and its direct link to Alexander the Great. It is, in fact, a dedicatory stele that contains, in 43 extensive lines, a letter received by Anaxarchus, an official from the Seleucid Kingdom. The letter served as a set of instructions to the locals on how they should care for the Temple of Artemis. It also provided clear evidence of the Greek presence on the island, reflected not only in shared religious practices and architecture but also in competitions, customs, and entertainment.

As Kottaridi wrote in a publication in Archaeology:

“Seleucus, the most Macedonian and at the same time the most cosmopolitan of all Alexander’s successors, his classmate and companion in battle, was the one who built the sacred fortress of Icarus following Macedonian principles. For centuries, it served as a greeting to ships arriving from the East.”

In this fortress, built according to the golden ratio, the nature and character of the new ruler’s power were imprinted—a manifesto of enlightened rule that envisioned the peaceful coexistence of nations. Kottaridi also emphasized that there were numerous Greek settlements and a strong Macedonian presence throughout the Persian Gulf. Along with the Greek archaeological mission, she played a key role in promoting the island as a site of historical and cultural significance.

Another major revelation was the discovery of a workshop where votive offerings related to the temples were processed. Among the findings were a spacious building, a small built-in oven, many vessels, and abundant food remains—including an entire bird. These discoveries suggested that the site’s destruction was sudden, likely caused by fire.

While previous Greek and international excavations had uncovered significant structures in the southwestern part of the island, the most recent discoveries are located in the north. For the first time, evidence confirms that the entire island hosted an extensive complex of temples, Hellenistic residences, and fortresses. This discovery underscores the immense strategic importance of the island for Alexander the Great and his generals.

The Significance of the Discoveries

According to announcements from the National Council for Culture, Arts, and Letters (NCCAL) and the archaeological mission of the University of Pergamon, the latest excavations on the island have uncovered an additional building, a courtyard, and a wealth of treasures. The rocky foundations that emerged led to an interior wall and an entrance opening into another chamber, where most of the findings—numerous ceramic objects from the Hellenistic period—were discovered. This site is now considered one of the most significant archaeological locations on the island, alongside the Temple of Artemis and previously discovered structures in the south. These findings further support theories that the island bears the imprint of Alexander the Great, whose image, notably, still appears on Kuwaiti coins today.

The intensive excavations carried out in the region over the past years—briefly interrupted during the COVID-19 pandemic—have revealed not only Hellenistic remains but also residences dating back to the 8th century AD, during the early Islamic period. These findings confirm the island’s abandonment towards the late 8th and early 9th centuries, followed by its resurgence in the 18th century.

Additionally, recent discoveries made just months ago by a Danish-Kuwaiti excavation team indicate that the island, which Alexander the Great deemed highly significant, was inhabited during the Bronze Age by the Dilmun civilization—one of the world’s oldest cultures.

The island’s immense historical and cultural importance is undoubtedly linked to its strategic geographical and geopolitical position. However, the newly discovered Hellenistic remains reinforce the idea that this island was not only established but also elevated in prominence by Alexander the Great and his generals, serving as yet another testament to his vast and enduring legacy at the far reaches of the known world.

Ask me anything

Explore related questions