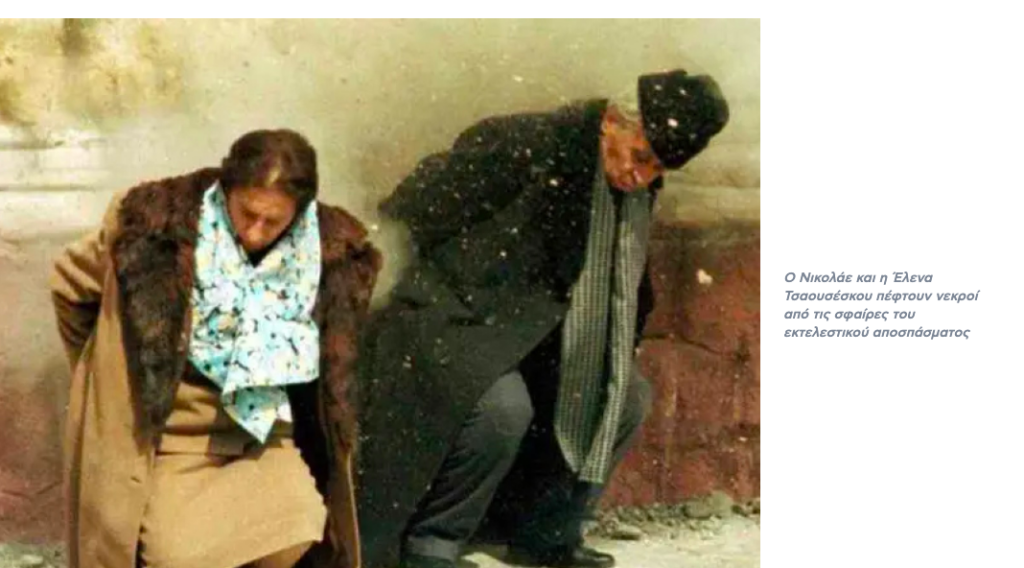

1989 was one of the most significant years of the previous century. The collapse of communist regimes in most countries and the fall of the Berlin Wall marked a series of cataclysmic changes in many states. Among these was Romania, where Ceaușescu’s regime collapsed in a matter of days. The “tyrant,” as many called him, was arrested with his wife Elena, tried in an expedited court, sentenced to death, and executed on Christmas Day, 1989.

Younger generations may be unaware of Nicolae Ceaușescu, while older generations likely remember the shocking video of the Ceaușescus being led to the execution squad and, shortly after, the frozen Christmas of 1989 in Romania, when they were shot dead. Despite the near-unanimous approval from the Romanian people of the execution, subsequent discussions have raised concerns about whether the trial followed due process. It also appears that many Romanians still nostalgically remember Ceaușescu’s rule…

Who Was Nicolae Ceaușescu?

Nicolae Ceaușescu was born on January 26, 1918, in Scornicești. He gained prominence as a member of the Romanian Communist Youth in the early 1930s and was imprisoned for his activities in 1936. He was arrested again in 1940 but escaped just before the anti-fascist coup of August 23, 1944, which overthrew the pro-German government of Ion Antonescu. Between 1944 and 1945, he served as the Secretary of the Union of Communist Youth. When the communists fully took control of the government in 1947, Ceaușescu took the position of Minister of Agriculture (1948–1950), and from 1950 to 1954, he served as Deputy Minister of the Armed Forces, holding the rank of Major-General. As a protégé of Romania’s Stalinist dictator Gheorghe Gheorghiu-Dej, Ceaușescu quickly ascended through the ranks of the Romanian Communist Party’s Political Bureau, becoming second in command within the party.

In March 1965, Gheorghiu-Dej died, and Ceaușescu succeeded him as the First Secretary of the Romanian Communist Party. By December 1967, he became the President of the State Council, thus becoming the leader of the country. When Ceaușescu rose to power in 1965, he was relatively unknown. However, he soon became very popular for pursuing an independent foreign policy, especially against Soviet pressure, particularly in matters of foreign policy and trade relations. During the 1960s, Ceaușescu effectively ended Romania’s active participation in the Warsaw Pact, and in 1968, he condemned the invasion of Czechoslovakia by Warsaw Pact forces.

Ceaușescu’s Domestic Policies – What Is He Blamed For?

However, Ceaușescu adhered strictly to orthodox communist policies when it came to domestic matters. Economically, his ill-conceived planning and investment policies led to the lowest living standards in Eastern Europe by the late 1980s. His government also maintained strict control over ideology and individual expression. By the late 1980s, basic consumer goods were distributed on rationing cards because Ceaușescu, in an effort to pay off the country’s massive external debt of $10 billion, exported much of the country’s agricultural and industrial production, leading to severe shortages of food, fuel, and other essentials at home. Similar to other countries in the former Eastern Bloc, though Romania had essentially withdrawn from it, Ceaușescu created the Securitate, the secret police, and installed a vast network of informants and spies to suppress any dissent, while also instituting a dynastic regime. He appointed over 30 relatives to positions of power and, according to rumors, amassed personal wealth worth tens of millions of dollars, with large deposits in foreign banks. Later parts of the article will examine how at least some of these allegations regarding his foreign bank deposits were unproven.

Elena Ceaușescu: The Wife of Nicolae Ceaușescu, Her Questionable Education, and the High Offices She Held

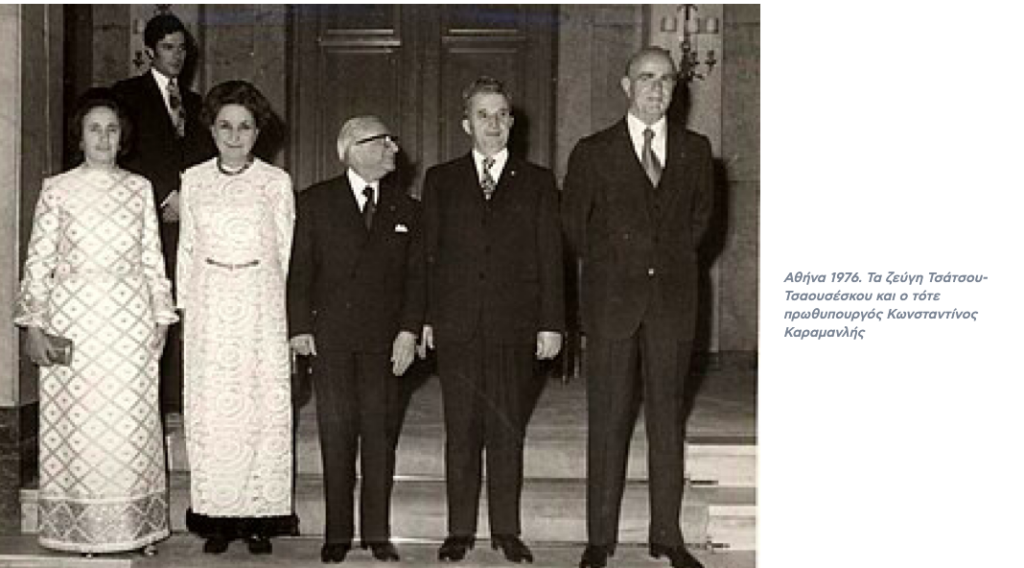

Elena Ceaușescu, born Lenuta Petrescu on January 7, 1916, in the Petrești commune in Dâmbovița County, Romania, came from a family of farmers. As was common at the time, Elena received only a basic education. After finishing elementary school, she moved to Bucharest with her brother, where she worked initially as a laboratory assistant and later in a textile factory. Strangely, when her husband became all-powerful, Elena appeared as a prominent chemist, despite not even holding a university degree. In 1976, the Academy of Athens even named her an Honorary Member, though this was done by decree, as we will see later in the article. Elena joined the Romanian Communist Party in Bucharest, where she met Nicolae Ceaușescu in 1939, and he quickly became infatuated with her. Their relationship was interrupted by Nicolae’s frequent imprisonments, but they eventually married on December 23, 1947. It’s likely that no other woman passed through Ceaușescu’s life as he was deeply in love with his wife.

Initially, Elena worked as a secretary in the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, holding an insignificant role until 1965, when her husband became the General Secretary of the Romanian Communist Party. That same year, she became head of the Central Institute of Chemical Research and, by 1979, head of the National Council for Science and Technology. In 1971, during a visit to China, Elena observed that Jiang Qing, the fourth wife of Mao Zedong, held true power in the state. This inspired Elena to take an active political role, leading to her high-ranking positions within the Romanian Communist Party. In July 1971, she was elected to the Central Committee of the Romanian Communist Party, becoming a full member by 1972. By March 1980, she was appointed first deputy prime minister and granted significant powers.

By the early 1980s, Elena Ceaușescu became the subject of personal adulation, so much so that she was elevated to the title of “Mother of the Nation.” Yet, she was also the one to introduce a series of unacceptable measures, such as the policy of leveling entire villages for “development purposes.” To increase the birthrate, she banned all forms of birth control and imposed mandatory gynecological examinations for all women of childbearing age. Many women died seeking abortions, turning to unqualified individuals since they were prohibited from visiting hospitals or licensed medical facilities.

The End of the Ceaușescus

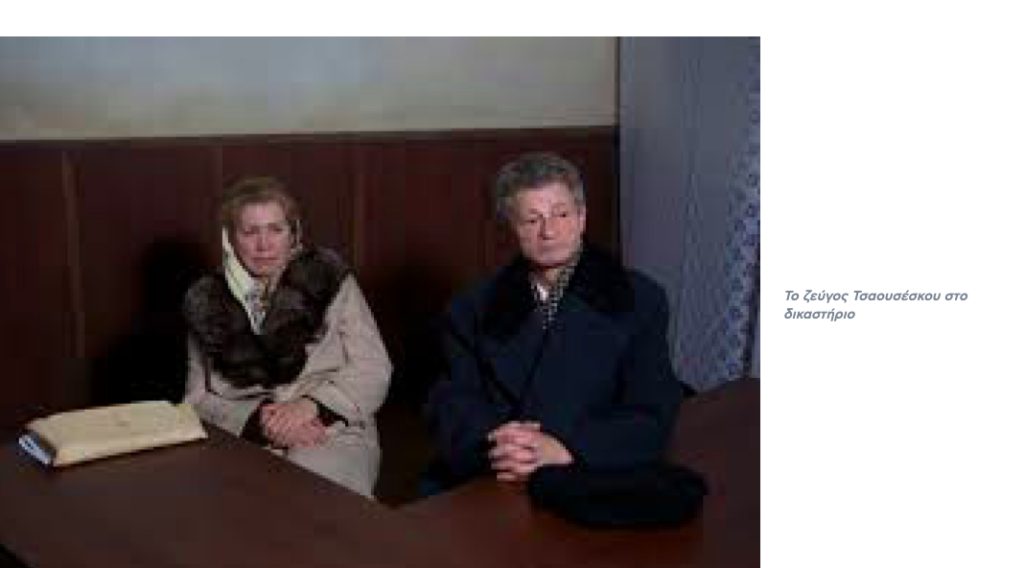

The end of the Ceaușescus was violent and shocking. Many considered their end to be what they deserved, while others noted that even basic legal procedures were not followed during their trial. Let’s examine the events of December 1989.

It all began in Timișoara, Romania’s third-largest city, located in the western part of the country in Transylvania, bordering Hungary and Serbia. It is a multicultural city with 21 ethnicities and 18 religions. Ceaușescu, fearing uprisings from minorities, had carried out purges in previous years to achieve ethnic homogeneity.

A first revolt against him in Brașov in 1987 was easily suppressed by the regime. László Tőkés, a Hungarian Reformed Church pastor in Timișoara, had been preaching against Ceaușescu’s “systematization” program. Having been a target of the regime for some time, he was ordered to be moved from his parish on December 15, 1989. As the day approached, Hungarian parishioners gathered outside Tőkés’ apartment, forming a human chain and preventing the Romanian authorities from acting. On December 15, a human chain formed outside his apartment, making it impossible for the authorities to intervene. Tőkés thanked the crowd but urged them to disperse. The protesters, however, refused, believing Tőkés was in danger from the Securitate. Many Romanians joined the Hungarian citizens, and the demonstration evolved into an anti-regime protest, chanting “Down with Ceaușescu.” Despite promises from the Mayor that Tőkés would not be relocated, the situation was already beyond control. The protests continued for the next two days. On December 17, 1989, the military began shooting indiscriminately into the crowd, with initial reports claiming thousands were dead, though this was later proven to be false. Between December 16 and 22, 1989, 73 citizens were killed, with 20 more dying after Ceaușescu’s flight. On Elena’s orders, 40 of the bodies were taken to Bucharest and cremated to prevent identification.

By December 18, thousands of industrial workers in Timișoara launched a peaceful protest. By December 20, 1989, the city was in full revolt, and news of the uprisings spread across the country, leading to the fall of Ceaușescu and his communist regime.

Ask me anything

Explore related questions