Every year on May 19, a heavy shadow looms over Greek collective memory—the shadow of the Pontian Genocide. This was a premeditated crime aimed not only at human lives but also at destroying the very continuity of a people’s history. The voices lost in the mountains of Pontus, the burning villages, and the death marches across Eastern Anatolia remain wounds for Greek heritage.

This date was officially designated as the Day of Remembrance for the Pontian Genocide. On May 19, 1919, Mustafa Kemal Atatürk disembarked in Samsun, marking the start of the second, deadlier phase of the genocide, which had begun years earlier and continued until 1923. During this period, approximately 353,000 Pontian Greeks—men, women, and children—were systematically exterminated.

Historical Context

In the early 20th century, the Ottoman Empire was in decline. After the Balkan Wars (1912–13) and the loss of large territories, the nationalist government of the Young Turks, despite promises of autonomy, took “preemptive measures” to ensure the survival of the state, transforming it into a solely Turkish nation. These measures included violent expulsions and the physical extermination of Christian populations across Asia Minor—Greeks in Pontus, Ionia, Cappadocia, as well as Armenians and Assyrians.

This was a systematic effort aimed at erasing the Greek presence that had lasted nearly 3,000 years in the Euxine (Black Sea) region. The persecutions started before World War I, targeting Greeks in Eastern Thrace and Ionia in 1914, followed by the Armenian genocide in 1915. By 1916, Greeks in Pontus faced the same fate.

The Young Turks’ nationalist ideology centered on the slogan “one state, one language, one religion, one people: the Turk,” viewing all non-Muslim communities as threats to the empire. Modern studies and the International Association of Genocide Scholars confirm that persecutions of Greeks, Armenians, and Assyrians were part of a broader plan to eliminate Christian populations in the Ottoman Empire.

First Wave of Persecution (1914–1918)

During WWI, persecutions in Pontus took the form of genocide under the Young Turks’ regime. From 1915, after the Ottoman defeat in the Caucasus, Turkish authorities accused Greek soldiers of collaboration and sabotage. Historian Vlasis Agzidis notes thousands of Greeks from Pontus were sent to forced labor battalions, where high death rates from hardships, hunger, and abuse were common. Conditions in these units were akin to death sentences.

Pontian Genocide: The Tragedy Unfolded

Many civilians fled to the mountains, organizing resistance and provoking brutal reprisals: in Kerasounta alone, 88 Greek villages were burned within three months, and around 30,000 Greeks were forcibly marched on foot toward Ankara through harsh winter, with a quarter dying from cold and hunger along the way.

By 1917, diplomats and foreign correspondents were aware of the unfolding catastrophe. U.S. Ambassador Henry Morgenthau warned that “Greeks, like Armenians, are targeted by the same extermination machine… This is not war; it is elimination.” In a November 1917 report, The New York Times described systematic destruction—thousands of Greeks in Samsun and nearby villages had already perished or were dying from starvation, disease, and executions, in death marches similar to those experienced by Armenians years earlier.

The Times reported that Turkish authorities were repeating the same methods used against Armenians: men were taken to the mountains and never returned, women and children followed only to die of starvation, villages burned, and churches looted.

Second and Deadliest Phase (1919–1923)

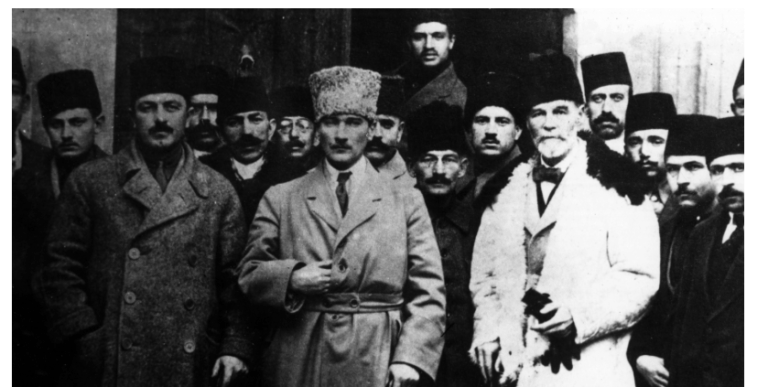

After WWI ended in 1918, the Allies imposed a ceasefire on the Ottoman Empire, but the persecution of Christian populations in the East continued. On May 19, 1919, Mustafa Kemal (later Atatürk) landed in Samsun to oversee disarmament of remnants of the Ottoman army but instead organized a new nationalist movement. Exploiting the inaction of major powers, Kemal launched a campaign of ethnic cleansing against Greek communities in Pontus.

Contemporary French newspapers described a “silent, insidious war of disappearance” in Pontus, even after the war’s official end. Correspondents spoke of a “silent Armageddon,” but appeals to the newly formed League of Nations went unheeded—international community either hesitated or chose to ignore the crime due to geopolitical interests. Turkish nationalist paramilitary groups, led by Kemal, ravaged Greek villages. On May 29, 1919, Kemal assigned notorious gang leader Topal Othman to “cleanse” Pontus of Christians.

The violence intensified: Samsun was set ablaze, and over 394 Greek villages were looted and destroyed, with inhabitants either massacred on the spot or deported inland.

In the next months, horrific atrocities occurred. In 1920, around 6,000 Greeks gathered in churches for protection in Bafra Province were slaughtered—most burned alive when their shelters were set on fire. An estimated 90% of Greeks in Bafra perished, with survivors forced on new death marches into the depths of Anatolia.

In 1921, the so-called Courts of Independence set up by Kemal in Amasya sentenced and executed hundreds of prominent Greeks, including clergy, elders, and educators, effectively dismantling local leadership. Numerous cases of rape and kidnapping occurred, with young women and children taken from their families and sold as slaves, completing the ethnic cleansing.

By 1923, with the signing of the Lausanne Treaty and the compulsory population exchange, the Greek population of Pontus was virtually uprooted. Survivors fled to the Caucasus, Soviet Union, or Greece, starting anew from zero.

The Toll and Personal Testimonies

Death marches were the primary method of extermination. Thousands—mainly women, children, and the elderly—were violently expelled from their homes, forced to walk long distances across mountains and deserts without food or water. Few survived. The Pontian genocide resulted in approximately 353,000 deaths.

The once vibrant Pontian Greek civilization—cities, villages, schools, churches, and rich culture—was almost entirely destroyed. A 2,500-year-old Greek community in the Black Sea region was eradicated, leaving scorched earth and abandoned settlements.

Survivor Testimonies

Eyewitness accounts are heartbreaking. Maria Texakalidou, a refugee from Samsun, recalled scenes of “300–500 dead bodies lying” and a baby still nursing from its slain mother among the corpses. Konstantinos Iordanidis described witnessing people eating rotting flesh and fierce fights over scraps in the streets. These testimonies, documented in historical records, serve as a sacred legacy passed down through generations to preserve the truth.

Remembrance and Recognition

For decades, the Pontian genocide remained a deep, unhealed wound. Greece officially recognized it in 1994 when Parliament unanimously declared May 19 as the “Day of Remembrance for the Pontian Greek Genocide”—symbolic marking the date in 1919 when Kemal’s forces began their final extermination phase.

Every year, memorial events are held across Greece. Descendants and officials honor the 353,000 victims through speeches, memorials, marches, and cultural events, affirming “We do not forget.”

The Pontian diaspora and organizations like the Pan-Pontian Federation continue advocating internationally for recognition. So far, only a few countries—Sweden (2010), Armenia (2015), and the Netherlands (2015)—have officially recognized the genocide. U.S. Senate resolutions also explicitly acknowledge it. Since 2007, the International Association of Genocide Scholars has confirmed that the mass killings of Greeks and Assyrians by the Ottomans form part of the same genocidal campaign that targeted Armenians.

Turkey, however, persistently denies that a genocide occurred, attributing the deaths to war, disease, or famine. The recognition of this crime remains a vital goal for the global Pontian Greek community. As the International Association of Genocide Scholars states, denying a genocide is considered its final stage—perpetuating impunity and paving the way for future atrocities. Recognizing and understanding the historical truth about the Pontian genocide is both a moral obligation and a necessary step against forgetting and future crimes.

Ask me anything

Explore related questions