On the occasion of the 572nd anniversary of the Fall of Constantinople to the Ottomans, we present the most recent information about Constantine, based on the distinguished work of the leading Byzantinist and Professor Emeritus of Medieval and Byzantine History at the University of Peloponnese, Mr. Alexis G.K. Savvidis, titled “For a New Biographical Dictionary of Byzantium: An Introductory Contribution,” Volume A, Papazisis Editions, second edition, 2024.

Who was Constantine XI Palaiologos?

Constantine XI Palaiologos, the last Palaiologos ruler (the tenth in succession) and the final defender of the medieval Greek world, was born in Constantinople (Byzantium) on March 12, 1405 (or, according to some sources, February 9, 1404). He was the fourth of six sons of Emperor Manuel II Palaiologos and the Serbian-origin Elena Dragaš, a scion of the prominent Serbian family of Dragas.

For this reason, Constantine XI is often referred to as Constantine Palaiologos-Dragaš. His father, Manuel II Palaiologos, reigned from 1391 until 1425. He was succeeded by his eldest son, Constantine’s brother, John VIII Palaiologos, who ruled Byzantium from 1425 to 1448. Constantine was co-emperor with his brother in 1423–1424 and again from 1437–1441.

572 years since the Fall of the City – His life, reign, and tragic end

After a brief stay in Tauris, Constantine went to the Peloponnese, where together with his younger brothers, Theodore and Thomas, they administered the Despotate of the Morea, completing the reconquest of the Frankokratia-held territories. Their residence and joint rule in the Peloponnese created tensions.

Eventually, Theodore and Thomas took over the administration of the Despotate. Constantine traveled to Constantinople to support his brother John VIII’s efforts. Later, after 1441, he returned again to the Peloponnese. However, the stance of Despot Constantine Palaiologos, supported by the Turks, brought him back to Constantinople (1442–1443), to bolster John VIII. From 1443 to 1448, he engaged in administrative and military reorganization of the Despotate in response to the Turkish threat.

Constantine XI Palaiologos, Emperor of Byzantium

When John VIII died childless in October 1448, Constantine’s brothers, Theodore and Thomas, opposed his accession to the throne. Their mother’s intervention was decisive, and on January 6, 1449, Constantine was officially crowned “Emperor of the Romans” at Hagios Demetrios in the Morea, then set out for Constantinople, arriving in March 1449. No other coronation is recorded in Hagia Sophia. Theodore and Thomas remained co-emperors at Mistra until 1460/61.

The Turks on the verge of Constantinople

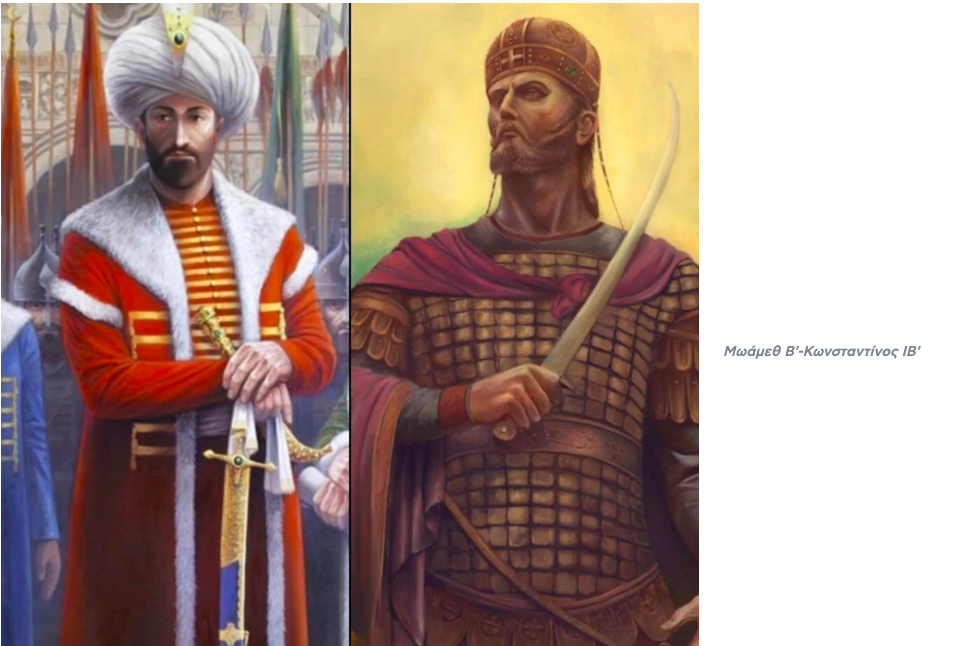

When Constantine ascended the throne, the Ottoman sultan was Murad V. Upon his death in February 1451, he was succeeded by his son Mehmed II (Mehmed the Conqueror), whose seat was then Edirne. Initially, Constantine XI maintained good relations with Murad and Mehmed. However, his support for Orhan, a rival claimant to the sultanate, strained relations further. From the beginning of his reign, Constantine understood that the Turks planned to attack and seize Constantinople.

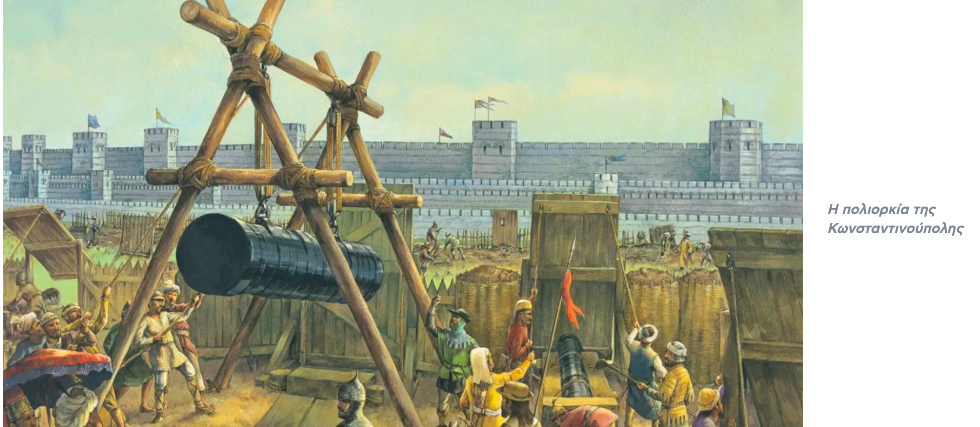

1452-1453: The siege and fall of Constantinople

Between April and August 1452, Mehmed II constructed the formidable fortress of Rumeli Hisar on the European side of the Bosporus, opposite the Anatolian Anadolu Hisar, built earlier by Bayezid I, known as the “Lightning” (1395/1396). According to Chalcondyles, from Rumeli Hisar, Mehmed could completely control the passage of ships to and from the Byzantine capital, whether via the Euxine (Black Sea) through the Bosporus or from the Sea of Marmara (Propontis) to the south.

The tightening Ottoman siege around Byzantium intensified after the victory of Mehmed’s pro-war allies, who ultimately prevailed over more moderate factions. The leader of these was Grand Vizier Halil Pasha Jandarli. It is recorded that Halil Pasha was bribed by the Byzantines to persuade Mehmed not to attack Constantinople.

Today’s Rumeli Hisar

Constantine’s desperate efforts to strengthen the city’s defenses

Faced with these circumstances, Constantine XI attempted to establish a modest defense. However, the empire had shrunk to Constantinople, some Aegean islands, and the Despotate of the Morea. He hoped for assistance from his brothers at Mistra, but they were attacked by the aging Turahan Bey (who died in 1456) and his sons Omer and Ahmed Bey.

His attempts to secure aid from Pope Nicholas V (1447–1455) and the West were unsuccessful. Furthermore, the dire economic state of the Byzantine Empire, burdened by substantial debts to Venice, and its debased currency—the poorly produced silver “stavrat” coins, which were very weak compared to the powerful Italian city-state coinages—added to the despair.

Additionally, Constantine, a moderate supporter of ecclesiastical union, aimed to recognize the Council of Ferrara-Florence (1438–1439). Yet, on December 12, 1452, he boldly led a joint Orthodox and Western liturgy in Hagia Sophia—an act that enraged many residents of the city. Most preferred the opinion expressed by the “Great Duke” Loukas Notaras, that he would rather see a sultan’s fez in Byzantium than a Latin mitre.

The unequal fight of the few defenders of Constantinople against the Turks

The Peloponnesian cardinal Isidore, who had previously served as Metropolitan of Russia, along with 2,000 foreigners—including 700 Genoese—led by the capable and brave John Longo Justinian, whose injury may have been the final blow to the city, added to the defending forces of 5,000–8,000 Byzantines. Opposing them were tens of thousands of Turks (estimates range from 100,000 to 400,000 depending on sources).

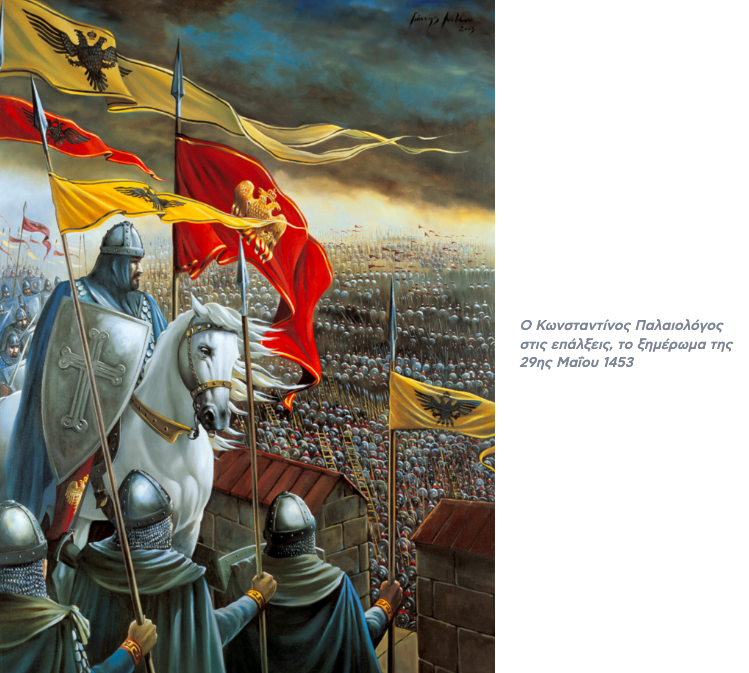

Constantine fought heroically surrounded by his officers and soldiers, refusing to surrender. After a 54-day siege (April 2–May 29, 1453), the city fell to the Ottomans. Constantine was killed, likely near the Gate of Saint Romanus. His trusted friend and historian, George Sphrantzes, was not present at his death to provide a precise account.

Assessment of Constantine XI Palaiologos

According to Alexis G.K. Savvidis, “the last Palaiologos is among the noblest ruling figures of medieval Hellenism,” although some modern historians question his political, military, and diplomatic abilities. Even the admirer of Mehmed II and chronicler of the fall, Michael Critobulus, influenced by Thucydides, compares Constantine XI’s leadership qualities with those of Pericles, despite not citing primary sources.

The Byzantines were deeply shaken by the fall of Constantinople, which was described as “the common Greek homeland, the seat of learning, the teacher of all sciences, the metropolis of cities,” according to the “Monody on the Unfortunate Constantinople,” written during that period by Andronikos Callistus, a humanist scholar and professor in Florence.

Why is Constantine XI (and not XI) considered the last Byzantine emperor?

Constantine XI Palaiologos was a fervent supporter of the revival of the national consciousness of Hellenism, which began to take shape after 1204—the first Latin conquest of Constantinople. Until recently, he was referred to as Constantine XI (the eleventh), but recent research indicates he should be numbered as Constantine XII (the twelfth).

The eleventh is now considered to be Constantine XI (Komnenos-Laskaris), co-founder of the Empire of Nicaea (1204–1205), along with his brother Theodore I Laskaris. This view was first proposed by the renowned Cretan Byzantinist and scholar, Konstantinos Amantos (1874–1960), around 1956. In recent years, this perspective has gained acceptance in both Greek and international scholarship.

The “Marmaromenos Vasilias” (The Marble King)

A recent legend

Constantine Palaiologos, as the “Marble King,” passes into the realm of myth

“Among the most popular themes in these legends (about liberation from Ottoman rule) is that of the ‘Marble King’—a motif common across Greek regions. According to one version, an angel appeared at the final battle on May 29, 1453, to save Emperor Constantine, who fought encircled by Turks. The angel took him from the battlefield and hid him in an underground cave near the Golden Gate, on the western side of Constantinople. There he was said to have remained marbleized (or sleeping) until God sent his angel again. The messenger of God would then wake the emperor, return his sword, and Constantine would emerge from the cave with his army, entering the city through the Golden Gate, and pursuing the Turks to the Red Apple hill, where he would slaughter them. The legend of the last Divine Liturgy in Hagia Sophia and the Holy Table was also widespread.

According to this tradition, the Turks entered Hagia Sophia during the service, just before the Divine Communion, and the priest vanished within the walls of the church. The interrupted liturgy would have concluded when the Greeks retook the city, at which point the priest would emerge from his hiding place to finish the service. Simultaneously, the Holy Table, which sank into the Sea of Marmara, would return to the church” (Spyridon Vryonis, “The Decline of Medieval Hellenism in Asia Minor and the Process of Islamization (11th–15th centuries)”, trans. K. Galatariotou [Athens: MIET, 1996, reprint 2000], pp. 388-389).

Ask me anything

Explore related questions