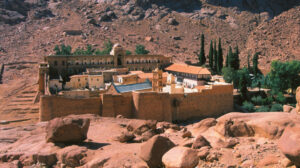

The true extent, nature and, most importantly, the true value of the property held by the Monastery of St. Catherine of Sinai seems like an open secret, that is, something that is being concealed while in the public eye – in theory at least, since there has been publication of the decision on what is to come from the Ismailia Court of Appeal.

In practice, however, few have access to the text of this highly controversial verdict, whereby the Egyptian state, quite succinctly, acquires a legal right to confiscate at will properties from the portfolio of the Monastery of Sinai. That portfolio includes at least 71 properties.

Arab law

However, the issue raised by the Court of Appeal’s decision, whereby the monastery’s tenants and trustees effectively have no legal ownership rights to properties that were considered the property of the monastery for 1,500 years, is sparking a very long debate. Apart from the fact that it is a twisted legal document of 160 pages, with the original written in Arabic ‘clear’ and translated into English, the decision echoes the logic and worldview of Arabic law, which differs significantly and substantially from Greek law.

Thus, critical and difficult questions arise, such as, for example, whether the 71 disputed properties include the monastery’s allotments abroad, i.e., not only outside the Sinai Peninsula, but also outside Egyptian territory altogether. And the issue of the shares is of key importance, given that the monastery has property in Egypt, Lebanon, Greece, and Cyprus. So it is reasonable and valid to be concerned about the fate of these properties, such as, for example, the church-next monument of St. Catherine in Plaka.

Of course, equally interesting is the parameter of value: How much, I wonder, is the portfolio of these 71 properties, which are scattered in at least four countries around the world and in a variety of settings, from hermitages of deserted monks in steep Sinai cliffs, to seaside plots of land, ancient monumental buildings and so on, valued? How many of these properties are ‘fillets’ jointly coveted by the Egyptian state and would-be investors for the construction of hotel complexes on Mount Sinai and with a privileged view of the monastery? How many and which of these are worthless plots of land, either because they happen to be too small and/or too inaccessible, lost somewhere in the rocky, lunar environment of Sinai?

Places and “seats”

Even in the arid rocky landscape that surrounds the historic monastery, there are, for example, the Gardens of the Holy Sarandas, with the springs that water the monastery, as well as some fairly large orchards, which perform a vital role, acting as natural food suppliers for the monks who settle in Sinai. Equally valuable for the survival of the monastery are the olive groves of Agioi Anargyroi, while an integral part of monastic life are the chapels, the metochia and the “seats”, the places of seclusion for the hermit monks, who withdraw from the mundane and devote themselves to communion with their Lord.

Properties of this kind make up the mosaic of fragmented, tiny properties, but they are an organic part of the Sinai Monastery. For example, its properties include the men’s skete on Mount Saint Science, with an operational monastic “seat”. There is an ancient chapel from the 3rd or 4th century AD, as well as the cell where for two years (1962-1964), Saint Paisios monastic monk, monk Paisios, monk of the Holy Trinity, lived, hence for many pilgrims, this is one of the top attractions of the Sinai Monastery – even if access to it requires an almost torturous mountain hike up to an altitude of 1,800 meters.

If the ultimate motive of Egyptians, behind the legal challenge to the monastery’s land ownership rights is the tourist development of the surrounding land, then it seems completely incomprehensible why the Egyptian state covets caves and ruined ascetics, a large number of which are scattered in the Sinai mountain range, in steep places, in valleys, etc.etc., but certainly also in Raitho, the point where the monastery exits to the sea.

Broadening the horizon of reference beyond the monastery and the area close to it, one of the thorny and complex issues raised by the latest legal processes in Egypt focuses on the fate of the shares. The properties, that is, are located in places of general interest to St. Catherine’s Monastery, even far away from Sinai and the monastery’s headquarters.

In the majority of cases, the metopes come from donations from the faithful or rulers, as was the case in earlier historical periods. In this way, in its long course, Sinai Monastery has acquired metochia almost everywhere in the world: from France and southern Europe to Russia and India. Today, many of the monasteries of St. Catherine’s Monastery remain in operation in Lebanon, Cyprus, Greece, etc., functioning as small “annexes” to the main monastery.

It is intended that Sinaite monks should reside in them continuously and be given the character of a small monastery, while the economic importance of the development of a network of metochia should not be overlooked, as income is created thanks to the fact that each metochi is usually accompanied by a productive farm or other property to be exploited.

Indicatively, metochia of the Sinai Monastery in Greece exist in Athens (temples and additional premises in the historical centre of Athens, in Agia Varvara Acharnon, in Alepochori of Megara), in Thessaloniki, in Crete and Ioannina.

The Greek reaction

Almost by reflection, an atmosphere of resentment is also being created, especially in Greece, because of the umbilical cord that has been connecting the Monastery of St. Catherine to our country for ages. And because the long-standing link is not only symbolic and religious, but inevitably entails some very serious political and economic implications, the confiscation of the monastery’s property is expected to lead to the reopening, once again, of the debate on Egyptian – and, in essence, Mosaic, in general – bacuffs in Greece.

First of all, a vakuf (Hellenization of the Turkish vakf) in the context of sacred Muslim law is any charitable initiative and any object, movable or immovable, donated for the benefit of the human community and a noble cause. The distinctive feature of a vakf is that it is identified with the higher, divine will, and, therefore, it is very difficult to sell, change its use, or even be subjected to a different management framework. In short, every bacoux is considered a “thing of divine right”-for Mohammedans, of course.

In Greece, mainly in the form of buildings, there are Turkish and Egyptian mosques. The establishment of the bacuffs in our country dates back to about the beginning of the 19th century and at first they were under Turkish-Egyptian management. since Egypt was part of the Ottoman Empire, the Egyptians participated as allies in Turkish military operations against Greece, such as Ibrahim in the Peloponnese, etc. Around the middle of the 19th century, between 1851 and 1854, an organization was established in Egypt specifically for the administration of the bai’s, and the situation remained stable for more than half a century, until about 1912.

Eventually, the recognition of property rights to Egyptian bacuzzis was agreed upon, something that applied predominantly in areas where there were several institutions of this type, the most typical being the case of Kavala, thanks to the famous and emblematic Imaret, a large workhouse that had dominated the city’s coastline since 1821, when it was built by Mohammed Ali, the later founder of the modern Egyptian state.

Imaret and Erdogan

However, it seems that the imarmeni, the “kismet” of the Mohammedan and especially the Egyptian bacuffs in Greece, foreshadowed only adventures. Which did not cease to complicate the status of the Waqf, carrying the shocks of the cosmogonic changes that were taking place in the very existence of Egypt. In 1948, Greece and Egypt reached a new agreement, which concerned the compensation to which the citizens of each country were entitled for material damage suffered during the war. These compensations covered both properties – Egyptian property in Greece and Greek property in Egypt.

Moving on to modern times, when Gamal Abdel Nasser came to power in Egypt, with statism and nationalism as the pillars of his policy, the Egyptian borders were negotiated with Greece. Indeed, a year later, Nasser sold several properties – even the mausoleum of Mohammed Ali’s mother – to the Greek state.

The next big change would come in 1984, on the occasion of another interstate agreement. This stipulated, among other things, that Greece would compensate Egypt for trespassing on certain buildings in northern Greece to the tune of 72,220,000 drachmas, while Imaret and Muhammad Ali’s house would remain Egyptian properties, due to their priceless historical and symbolic value. Over time, however, the care of the buildings by their rightful owners was not appropriate – far from it. Indifference and decay were evident, in a painful way, especially on the face of the Imaret, which had been left for many years as a pawn to the imposition of any destroyer, living or otherwise.

Before the destruction of the monument became irreparable, a Greek private initiative intervened to save it, the soul of which was Anna Missirian, a member of one of the most prominent and wealthy business families of Kavala. In 2001, Mrs Missirian, representing “Imaret S.A.,” leased Imaret for 50 years from the Egyptian Wakufi Organization.

Without sparing any expense, Imaret was fully restored in an exemplary manner, with the extensive use of traditional materials and methods, to serve as a monument-hotel, as well as a center for the study of Mohammedan culture and an institute for research into the life and state of Muhammad Ali.

However, despite the fact that Turkish and Egyptian officials declared themselves admirers of the project, the political backstage was working on plans not at all auspicious for Imaret and the bureaucrats in general.

Around 2012, when the dominant force on the Egyptian political scene was the Muslim Brotherhood – and, coincidentally, Greece was plunged into economic crisis – Recep Tayyip Erdogan managed to persuade Egypt’s then-leader Mohamed Morsi to make an internal exchange of bacuffs: Turkey would cede to Egypt certain Cairo mosques and Egypt would reciprocate the gesture by transferring Imaret. In the end, the verbal and initial agreement, for rather circumstantial reasons, never materialised. However, everyone can imagine what kind of foothold Turkey would have gained in Greece by using as a Trojan horse an internationally prominent and prestigious mosque, the Imaret of Kavala. As anyone can easily guess what a possible revival of this indirect expansionism would mean, this time with the ownership of the Monastery of St. Catherine of Sinai at stake.

Ask me anything

Explore related questions