I heard Rena’s voice, his wife, on the phone telling me: “He’s not here, he’s somewhere around Evia with the boat.” What could I do? I dialed his number and the first thing he told me was “I can’t talk now, call after 8 in the evening.”

Beforehand, I had made a little research about the legendary case of Kostas Thoktariadis. So, I imagined him running at a depth of 212 meters and exchanging kisses with the fish. Like astronauts flying in space? Something like that at the depths of the Greek seas.

Thoktariadis is well known to the British Admiralty officials as well as the French equivalent. The researcher who, among other things, discovered seven sunken submarines—mostly from World War II: three British, one German, one Italian, and two Greek. The top diver who discovered the sunken British ocean liner “Arcadian.” Then, in his insatiable passion for research, he managed to locate the incredible case of an Englishman, Thomas Thrulfol, who held an unbelievable survival record. He had survived both the Titanic and the Arcadian!

From this phone conversation, I took three things with me. First, that in diving you don’t fear sharks but your own mind. Second, that there are more dangers on land from people than in the depths. And third, “Man is an invader of the sea, entering an environment where he essentially shouldn’t be. We are guests, we enter, look around, and leave.”

To understand the greatness of his passion, he baptized his only daughter Agapi-Okeanida (Love-Oceanid)! And he trained her in diving since she was only 5 years old!

Scene 1

“Walker” of the seabed

Dimitris Danikas: Where do I find you now, Kostaras?

Kostas Thoktariadis: I’m in Northern Evia with the boat. The professional one we use for work. It’s 9 meters, small.

D.D.: And what are you doing there?

K.Th.: We’re a team of five, doing industrial-type work. I can’t say more; there’s industrial secrecy.

D.D.: Are you diving?

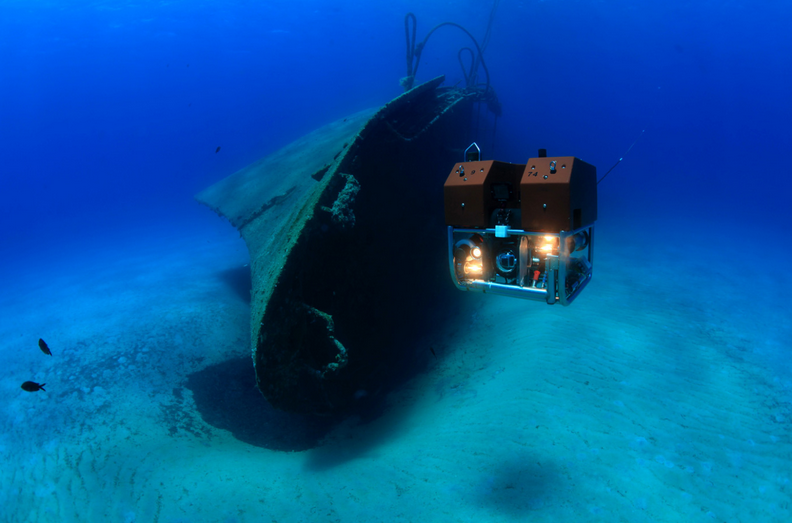

K.Th.: No, we haven’t been diving for years. Mainly we work with robots, remotely operated underwater vehicles.

D.D.: Why don’t you dive anymore? Are you afraid?

K.Th.: No, it’s not about fear. I’ve just been working for a long time now with underwater robotic systems that are unmanned vehicles.

D.D.: And you control them?

K.Th.: Yes, from the boat. They usually conduct underwater research or inspections.

D.D.: Do you work for the government or just private companies?

K.Th.: Both, many times for the government, for industries, in the gas & oil sector, and on cables…

D.D.: What cables?

K.Th.: Repairs of underwater cables, old cables that break. High voltage cables that connect islands and supply power. If one breaks and is very deep, where no person can go, we send down robots.

D.D.: How deep can the robot go?

K.Th.: Up to 1,000 meters.

D.D.: How deep have you gone?

K.Th.: In the past, in 1995, I reached 212 meters.

D.D.: That deep!

K.Th.: Yes, I specialized in deep diving with gas mixtures.

D.D.: What are these gas mixtures? Explain to us.

K.Th.: They are gases that allow someone to go deep, made up of helium, nitrogen, and oxygen. A mixture of these. Because nitrogen, for example, causes narcosis that prevents a person from going deeper than 50 meters.

D.D.: How did you start?

K.Th.: I saw a documentary on YENED (Greek TV), a tribute to frogmen. It was very impressive what I saw and I had questions about what the seabed is like. I was fascinated by the underwater environment. When I got the chance, I tried diving. At first, I wasn’t doing well, I didn’t feel comfortable. So, I decided to dedicate myself more to feel better. It took me time, and so I had to engage more deeply. I started to like it a lot and decided to pursue it professionally, specializing in deep diving and shipwrecks. I trained in England and France, in their official schools. The French school is INPP (Institut National de Plongée Professionnelle) and the English one is Fort Bovisand. I stayed there for several months and did full training. I must tell you, the British and French are way ahead. That’s where I used diving suits for the first time—both old and new.

D.D.: So the greatest tradition is held by the English and the French?

K.Th.: Yes, the English because of the North Sea and oil, they developed professional training a lot. And the French because of Cousteau.

D.D.: What about Americans, Norwegians?

K.Th.: Americans less so, actually they come last. Norwegians are good, but the great tradition belongs to these two schools, the English and the French.

D.D.: Previously you had gone to university, had you studied something else?

K.Th.: No, I only dealt with this. Later, I worked with the submersible “Thetis,” which Greece bought in 1999. It is the first and only research submersible the country acquired. The pilot and one passenger went inside. I was responsible for the vessel and its operator. There was also a team including a second pilot and maintenance crew.

D.D.: How deep did you go?

K.Th.: Up to 610 meters.

D.D.: And could you get out of it?

K.Th.: No, it was airtight and maintained atmospheric pressure. It recycled the atmosphere with a special chemical system that absorbs carbon dioxide and adds oxygen. So, you could move around underwater.

Scene 2

The “harmless” sharks

Dimitris Danikas: The submersible looks like a spaceship of the seabed. That’s how director James Cameron, who made films about it, describes it.

Kostas Thoktariadis: Yes, he has used submersibles. I would say the environment is just as inhospitable as space. An environment unfriendly to humans; it’s unnatural for humans to be underwater.

D.D.: Have you seen sharks? Were you afraid?

K.Th.: Fear isn’t an issue; in Greece, sharks are extremely rare anyway. I’ve seen them two or three times.

D.D.: Did they approach you?

K.Th.: No, they just passed by. You can feel more awe than fear. Usually, they are harmless creatures.

D.D.: A harmless shark? Spielberg says otherwise in “Jaws.”

K.Th.: That’s fiction, it doesn’t reflect reality. It’s very rare to see a shark and even rarer for it to attack.

D.D.: Have you encountered anything else inhospitable in the depths?

K.Th.: No, I mainly did salvage work. It’s a very specialized job, not well known in Greece, very few people do it.

D.D.: Don’t the frogmen do this?

K.Th.: Frogmen are mainly diver-warriors. They also dive with breathing apparatus but operate on a military level.

Scene 3

Agapi-Okeanida

Dimitris Danikas: You have a daughter, if I’m not mistaken.

Kostas Thoktariadis: Yes, Agapi. Agapi-Okeanida. We work together. She’s been diving since she was little, from 5 years old. Now we mainly work with remotely operated underwater vehicles.

D.D.: Agapi is your only child, right?

K.Th.: Only, only. As far as I know… (laughs)

D.D.: Ha ha, nice. Does your wife dive?

K.Th.: She is trained. She dived in the past, but it’s not something she really likes.

D.D.: Did you meet her underwater?

K.Th.: No, at ANT1 (a TV station). She was a journalist and we met during a report. You might remember her; her name is Rena Giatropoulou. It was a report about Monachus monachus seals, which Rena was covering, and that’s how we met in 1994.

D.D.: And your child started diving at 5 years old. With normal gear?

K.Th.: Initially with children’s equipment. A bit of diving in the summers; in winter she did competitive swimming at Ethnikos Piraeus and since she was young had a very good affinity with water, a very good relationship with the liquid element. We made it like a game. Gradually she did more diving. In recent years, she is a pilot—the first certified female ROV pilot (remotely operated underwater vehicles) in Greece.

Scene 4

Wet graves

Dimitris Danikas: Let’s move on to your discoveries. What are the biggest ones? Have you found any ancient artifacts?

Kostas Thoktariadis: I haven’t personally worked with ancient artifacts, except for several missions I participated in earlier with the Ministry of Culture. These were various programs of the Ephorate of Underwater Antiquities, and I participated as a team member. Personally, I have dealt with modern shipwrecks.

D.D.: What have you discovered?

K.Th.: War submarines. I have found three English, one German, one Italian, and two Greek.

D.D.: Were these from World War II?

K.Th.: The French one was from World War I, the rest from World War II.

D.D.: Do you remember where they sank?

K.Th.: In various locations in Greece: Kefalonia, Mykonos, Donousa, Skiathos, Kavo Doro.

D.D.: In what condition did you find them?

K.Th.: Almost in excellent condition, except for one that had exploded and was cut into three pieces. The others were intact.

D.D.: Were there skeletons inside?

K.Th.: In most, you can’t see inside because they are closed off, you can’t look inside.

D.D.: Have they been raised?

K.Th.: No, never. They are wet graves and remain as they are on the seabed.

Scene 5

The hobby

Dimitris Danikas: For these discoveries with the submarines, were you paid?

Kostas Thoktariadis: No, these are hobbies. Discovering shipwrecks and maritime history has been a favorite hobby of mine since I was 18.

D.D.: You must have studied a lot of Greece’s maritime history.

K.Th.: Yes, it’s very important. I have mainly dealt with modern maritime history, from World War I onward. It’s a very important history documented in Greek bibliography and archives. Likewise, we research their history in foreign archives.

D.D.: And the foreigners have given you access?

K.Th.: Of course, they have no problem at all. On the contrary, they like it, especially when the work is organized and systematic. For them, it’s a promotion of their maritime history and they seek it. It’s a revelation of the past, true stories that have not been told.

D.D.: Have you ever thought of making documentaries about all this, showing it on screen?

K.Th.: No, I don’t deal with that. We do our work and beyond that…

D.D.: When you say “we,” how many are you? Do you have a company?

K.Th.: Yes, we have a company and when we don’t have jobs and have free time, we often deal with these shipwrecks.

D.D.: When you say “jobs,” do you mean industrial jobs?

K.Th.: Yes, industrial but also shipping-related, with ships. Many times we search for anchors, do inspections on pipelines, things like that. We have a large client base in Greece and abroad.

D.D.: Where abroad?

K.Th.: In various countries. Recently we made two trips to Saudi Arabia.

D.D.: What did they want there?

K.Th.: Inspections with robots during the handover of a port. We check how the port is when the constructor delivers it to the client. This is done with robotic machines and we operate them.

D.D.: When did you start with the robots? When did you stop diving?

K.Th.: I started working with robots and got trained in 1998. I still dive, but in recent years I don’t do professional diving.

D.D.: Because you got older?

K.Th.: I’ve grown older on the one hand, and on the other hand, the robots work very well. I have extensive experience, over 10,000 hours as an operator. We do it very systematically and we have built a fleet of robotic vehicles.

D.D.: How many do you have?

K.Th.: Seven.

D.D.: Are these robots very expensive?

K.Th.: They’re specialized; price is not the main issue. They require special maintenance knowledge, which we have. We do the maintenance ourselves, me and my daughter. Maintenance, conversions, modifications—we handle that technically too. These robots are French-made, all the same brand, so they share parts. We avoid complexity.

Scene 6

The castaway

Dimitris Danikas: How many days a year do you spend at sea?

Kostas Thoktariadis: It’s not fixed, but definitely over 100 days a year we spend working at sea.

D.D.: Besides the submarines, what else have you encountered “walking” on the seabed?

K.Th.: We have examined the Arcadian, a British ocean liner that sank during World War I in Greece after being torpedoed by a German submarine.

D.D.: Were there passengers onboard?

K.Th.: It was requisitioned by the British Admiralty and was carrying military personnel to the Middle East. It was torpedoed by a German submarine operating in the Aegean. There is a lot of material about it. A very interesting fact is that among the crew was a castaway from the Titanic who had survived that sinking and then sank again four years later.

D.D.: Incredible story, that’s a movie script! He survived the Titanic and then sank with the Arcadian.

K.Th.: He survived that too! Twice he survived! Actually, the two shipwrecks happened on the same day four years apart.

D.D.: No way! What was his name?

K.Th.: Thomas Threlfall.

D.D.: When did you discover the Arcadian?

K.Th.: Last year, in 2024.

D.D.: Did you find it by chance?

K.Th.: No, it was a mission; we had done research in England and planned it.

D.D.: On behalf of the British government?

K.Th.: No, we do these for ourselves, for fun. We’re not paid, nor do we have sponsors.

D.D.: How did you think of searching for the Arcadian?

K.Th.: I have studied all the ships lost in Greece. There’s a database of over a thousand ships lost since World War I. We create detailed files to which we keep adding information — which ship sank, how it happened, the ship’s log, survivor testimonies, all that. And when the timing fits — we happen to be in the area for work, have free time, good weather, and spare funds for fuel — we might do something. Missions like that happen by chance.

D.D.: How many stable partners do you have in this?

K.Th.: Mainly my daughter and some sailor friends who love history and pursue it as amateurs. Often we create joint projects and work on the history of a ship for two, three, five, ten years until we find it.

D.D.: What impressed you most from all this?

K.Th.: The human stories stand out.

D.D.: Tell me one.

K.Th.: For example, the British submarine Perseus, which had a single survivor. It sank on December 6, 1941. One man managed to escape. He got out of the sunken submarine, surfaced, and survived. Greeks hosted him for many months in Kefalonia, moving him between houses, risking being arrested and executed by the Germans. They fed him even when they had no food themselves, helped him, and he escaped abroad. His escape was arranged voluntarily by a Resistance legend, Captain Houmas, who organized escapes with caiques. He was from Samos and with a small 9-meter caique took on the task to cross the occupied Aegean, find him, and smuggle him to Turkey. From Turkey, he was taken to the Middle East. There, he gave testimony about what happened, how the submarine was lost, why he was the sole survivor. This, you see, is part of the story of the submarine Perseus that sank near Kefalonia.

D.D.: Have you ever encountered illegal immigrants on your way?

K.Th.: No, never happened.

D.D.: What’s the toughest sea in Greece?

K.Th.: The two toughest, the most difficult waters, are the Karpathian and Ikaria seas. And third, I’d say, Kavo Doro. These three have many shipwrecks and are rough seas even for experienced sailors. Everyone suffers passing through them. They’re beautiful seas but very wild.

D.D.: Have you “walked” all over the Aegean?

K.Th.: I’ve been almost everywhere in Greece. I really love the Aegean and Greek seas in general. The Ionian is milder. It has bigger waves but is gentler, more pleasant. The Aegean has the meltemi winds, often strong weather, and blows harder, especially in the central Aegean.

Epilogue

Invader in the sea

Dimitris Danikas: What has been the best personal moment in your life?

Kostas Thoktariadis: The best moments are with my daughter. When I’m working together with her. Like now, while we’re talking, I’m with her.

D.D.: And the most unpleasant moment so far? Something you regret?

K.Th.: At sea, I have no regrets; I have almost only good memories. I feel more danger on land than at sea.

D.D.: So you think you’re more at risk from people on land than from fish at sea?

K.Th.: Yes, yes. Humans are invaders of the sea. We’re visitors capturing images.

D.D.: And the future?

K.Th.: I’m 56 now and will mainly focus on robotics and history. My mission is to equip my daughter with the technical knowledge and information so she can continue this work she loves. It’s something we do with love, a profession we would even do as amateurs. We’d pay to do this work.

D.D.: Such great passion!

K.Th.: Yes, it’s something done with passion and dedication. That creates joyful moments. This work is a bit tough, but very beautiful to do.

Before we finished, I managed to ask him, “All these years, have you ever been in danger?”

He said, “With robotics now, there’s no risk. In the past, with diving, the danger came only from your own mind. A person is more at risk from panicking and losing control than from the environment itself. When diving, you don’t risk fish, but your own mind.”

I imagine him running at 212 meters deep, shaking hands with harmless sharks. And they say to him: “Back again, Kostas? Maybe you’re a fish and you don’t even know it.”

Ask me anything

Explore related questions