They’re impressive and otherworldly. Some of them glow in the dark. At the mere mention of them, beachgoers panic. Whether you call them jellyfish, stingers, or by their scientific name—like Pelagia noctiluca—what’s really going on in Greek waters this summer? Are their numbers really exploding, and how worried should we be?

“Not at all,” say scientists at specialized marine research centers, explaining that this isn’t a new phenomenon for Greece. Seasonal blooms occur based on various factors—from water temperature and wind direction to the amount of organic waste in the sea. These outbreaks eventually subside. Still, if you’re unlucky or careless, you might end up with itchiness, redness, or even burns from close contact with a jellyfish—or the mucus it leaves behind in the water.

12+1 Truths About Purple Jellyfish

- Older than dinosaurs: Jellyfish have existed in the oceans for at least 500 million years.

- No brain, heart, or bones: They function with a neural network, like an underwater Wi-Fi system, allowing them to respond to light and movement.

- Biologically immortal: The Turritopsis dohrnii can reverse its aging process and return to a larval stage.

- Mostly water: Jellyfish are 95–98% water. Out of the water, they evaporate within hours, leaving nearly nothing behind.

- Giant tentacles: The Cyanea capillata or “lion’s mane jellyfish” can reach 36 meters in length (including tentacles).

- Lethal venom: Australia’s box jellyfish has venom 100 times more potent than a cobra’s.

- One hole for everything: Jellyfish have a single opening that serves as both mouth and… toilet.

- The mythological Medusa wasn’t a jellyfish: The famous Gorgon with snake hair and a petrifying gaze had nothing to do with the sea creature.

- Ancient symbol of protection: From the Parthenon to Vergina, Medusa’s head was used to ward off the evil eye in ancient Greece.

- Bad omen in dialects: In some island dialects, saying “I saw a jellyfish” means bad luck is coming, especially if you step on it with an oar or drag it ashore.

- Human impact: Overfishing and warming seas lead to jellyfish population explosions, threatening marine ecosystems.

- They glow! Many jellyfish, like the purple ones, exhibit bioluminescence—they can produce their own light. Ancient Greeks may have mistaken them for sea nymphs.

+1. They’ve inspired our culture: From Versace’s logo to ancient mosaics on Delos, jellyfish have left their mark on art and mythology.

Sea Turtles

“Why me? And why now?” That’s the common cry of someone who’s had an unfortunate—and painful—encounter with a jellyfish. The answer lies in environmental conditions: warmer waters, ocean currents, jellyfish reproduction success, and even overflowing sewage can trigger a bloom.

Scientists agree that jellyfish surges are mostly caused by humans, mainly through actions that remove their predators from the ecosystem. The most famous of those predators is the sea turtle, whose numbers are declining due to accidents and deliberate killings.

Ironically, many turtles choke on plastic bags, mistaking them for jellyfish. Others fall victim to fishing gear or even intentional head trauma. Greek environmental groups have documented hundreds of attacks on turtles, some estimating up to 1,000 per year.

A Couple of Striking Cases from 2022

- A 1.3-meter male sea turtle was found beaten and strangled with a rope near Diakopi beach in southern Pelion—an area later plagued by purple jellyfish, a primary food source for loggerhead turtles (Caretta caretta).

- In Agia Anna beach, Naxos, swimmers watched in awe as “Marios,” a male sea turtle, appeared offshore and cleared the waters of jellyfish. In just 30 minutes, he ate more than 100 purple jellyfish, making the beach safe again.

So while jellyfish may seem like villains of the summer, the real issue lies with human activity—both in disturbing marine ecosystems and in harming their natural predators.

And yet, as paradoxical as it may seem, some of the dead turtles are killed by fishermen who see them as competitors—accusing them of stealing fish or tearing their nets. The irony? Jellyfish feed on phytoplankton and zooplankton, which are the food fish need to grow, as well as on fish eggs. They also often trap and consume small fish in their tentacles. It’s a vicious cycle triggered by the disruption of the natural food chain: jellyfish consume the eggs of fish that would otherwise prey on them, but those fish are now nearly extinct due to overfishing.

It’s no coincidence, then, that scientists from the environmental organization Archipelagos, commenting on the panic caused by the appearance of purple jellyfish—mainly in the Pagasetic Gulf and on beaches in Evia—point out that the real issue isn’t jellyfish or their numbers, but the loss of their natural predators: fish species suffering from intense overfishing. And they’re right. Two of the jellyfish’s top natural predators are tuna and swordfish, but they’re far from the only ones.

According to current data, European seabass (Dicentrarchus labrax) actively hunt jellyfish in coastal areas, especially when they’re young and small. They’ve also been observed eating jellyfish eggs and larvae, and even entire small jellyfish. Gilthead seabream (Sparus aurata) has also been recorded eating small jellyfish or parts of them, particularly when other prey is scarce. The greater amberjack doesn’t hesitate to bite into larger jellyfish like Pelagia noctiluca (the purple jellyfish), cutting them apart with its teeth. Horse mackerel has been seen biting jellyfish when they appear in large numbers in its habitat, as has the grouper. Meanwhile, many small pelagic species—like sardines and anchovies—while not actively hunting jellyfish, feed on their drifting eggs and larvae.

However, these fish are no longer present in large numbers, say scientists, because bottom trawlers sweep the seafloor clean. Add to that the effects of climate change, which not only boosts jellyfish reproduction, but also alters underwater currents. A temperature increase of just one degree Celsius can shift a current’s course, potentially bringing jellyfish swarms into areas where they were never seen before.

Beyond that, aside from rising sea temperatures that support jellyfish population growth (climate change and overfishing are globally recognized as the two main factors influencing Pelagia noctiluca populations), on a local level, another contributing factor is the steep slope of the sea floor. This topographic feature is found in areas such as the Gulf of Corinth, among others, where large concentrations of purple jellyfish have been observed near beaches adjacent to underwater canyons.

Reproduction

“The great depth and steep slopes enhance the vertical movement of organisms by creating vertical currents,” say researchers.

There are also cyclical appearances. Some species experience population surges every seven years, every decade, or even more frequently. This happens when there’s a successful reproductive season and other conditions are favorable.

Professor Emeritus of Biology at the Aristotle University of Thessaloniki and marine life expert, Chariton-Charles Chintiroglou, has explained that population booms can be linked to weather conditions, such as northerly winds, which can transport populations from one region to another, as well as to the geomorphology of each area. Since the 1970s, the species has become a common presence in Greek waters, with small or larger population surges occurring in cycles. These surges often follow a successful reproductive period, such as in 2022. Typically, a population spike is observed every seven to ten years. Prof. Chintiroglou has noted that—though not yet scientifically confirmed—in some areas the increase in the population of the purple jellyfish may be related to organic pollution. These are organic waste materials that cannot be processed through biological treatment plants, possibly leaking due to overflowing cesspits. Such local organic pollution may provide a food source for jellyfish, thus contributing to population growth.

Species

In recent years, the most “trendy” species is the purple jellyfish, not because it glows in the dark and is visually impressive, but because swarms have taken over northern Evia, an outlet for the Pagasetic Gulf to the open sea, where jellyfish also appear in large numbers, especially along the eastern coasts. The Hellenic Biodiversity Observatory has reports of jellyfish spreading as far as the northern Sporades, with confirmed sightings in Skiathos and Skopelos.

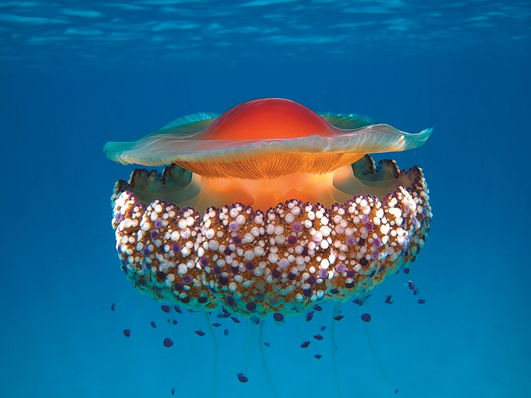

According to the National Public Health Organization (EODY), it is a marine organism capable of bioluminescence. It is a small, multicolored species whose tentacles and bell (which is unusual for jellyfish) are covered in stinging cells. Stings are common and painful, and symptoms can persist for a long time, though they are generally not dangerous. Swarms of Pelagia noctiluca have been known to devastate entire fish farms, making it one of the most studied jellyfish species.

Scientists from the Archipelagos Institute explain that Pelagia noctiluca, or purple jellyfish, is responsible for the most frequent jellyfish blooms in certain areas. These events are usually local and temporary and occur mainly in spring, summer, or autumn. They are particularly noticeable in regions where populations of their natural predators—such as tuna, sea turtles, and various fish species—have decreased, mostly due to overfishing. Their presence is also supported by warmer sea temperatures, calm seas, and changes in ocean currents, which can carry them en masse to shore.

The purple jellyfish is generally small (up to 12 cm in diameter), with a characteristic orange-brown or pink/purple color and strong spots, and has long, trailing tentacles reaching up to 2 meters. Its sting is quite unpleasant.

But it’s not the only one. The second most well-known jellyfish in Greece is the blue jellyfish (Rhizostoma pulmo), one of the largest in the Mediterranean, with a large, hemispherical bell. Its sting is mild and rarely causes problems for humans. Still, some caution is advised: this species secretes mucus, and if someone swims too close, they should avoid touching their face, as mild swelling may occur. The blue jellyfish has a distinctive iridescent purple ring around its bell, a body ranging from milky white to deep blue, and instead of thin tentacles, it has thick, lobed appendages.

In Greek waters, according to Archipelagos, you may also encounter:

Chrysaora hysoscella, known as the compass jellyfish. Occasionally found in Greek seas. Contact should be avoided as it can cause intense irritation.

Cotylorhiza tuberculata, commonly known as the fried egg jellyfish. Frequently found in Greek and Mediterranean waters. Completely harmless to humans. It often hosts small fish (such as sardines or anchovies) that find shelter among its tentacles. It plays a positive role in the marine ecosystem by filtering water and maintaining plankton balance.

Rhopilema nomadica, a species previously found only in the Indian and Pacific Oceans. It entered the Mediterranean through the Suez Canal in the 1970s and was first recorded in Greek waters in 2006. It has caused problems due to population surges in southern Mediterranean areas (e.g., Israel), primarily because of its potent sting.

Guidelines

“You’ll only be saved if you pee on the sting, or rinse it with fresh water.” Such old advice for jellyfish stings not only makes scientists scoff, but also causes victims unnecessary pain. A jellyfish sting is no joke—some toxins released upon contact with the skin can cause anything from itching to a burn-like allergic reaction and may leave marks lasting over a week. They’re called “τσούχτρες” (stingers) for a reason.

This is because jellyfish tentacles contain cnidocytes, which, upon skin contact, release nematocysts—toxin-filled capsules that cause itching.

According to EODY, these nematocysts can produce redness, swelling, burning, and sometimes serious dermonecrotic and cardio-neurotoxic effects, which are especially dangerous for sensitive individuals.

Symptoms of a sting may include:

- A burning pain

- Redness or visible jellyfish imprint on the skin

- Nausea, drop in blood pressure, rapid heartbeat, headache, vomiting, diarrhea

- Bronchial spasms, difficulty breathing

If someone exhibits systemic symptoms (rare), such as low blood pressure, voice changes, wheezing, generalized swelling (angioedema), widespread hives, confusion, or vomiting, they must be taken to a hospital immediately.

If stung by a purple jellyfish:

- Do not urinate on the area, rub it with fresh water, vinegar, alcohol, ammonia, or cover it with a bandage.

- Do not use vinegar: while effective for some jellyfish stings, it is not suitable for the purple jellyfish.

- Fresh water can cause more nematocysts to rupture due to its lower osmotic pressure.

- Gently rinse the irritated area with sea water—do not rub.

- Remove any attached tentacles using tweezers, a knife, or a plastic card, never bare hands.

- If you don’t have a tool, you can rub sand gently to detach the tentacles.

- Apply ice or cold compresses to reduce swelling and discomfort.

- Use cortisone cream to relieve inflammation, stinging, and itching.

- Take an antihistamine to manage itching or systemic symptoms.

- If symptoms persist or worsen, a cortisone injection may be necessary—seek medical help.

Robot Hunters

In years when jellyfish populations boom and their presence at beaches could hurt tourism—unless a natural “hero” like Marios the sea turtle (who cleared the beach of Agia Anna in Naxos in 2012 by eating all the jellyfish) appears—there are alternative, though costly and not always effective, solutions.

In South Korea, a high-tech method has been adopted: robotic underwater drones patrol areas where jellyfish are unwanted. When they detect swarms, the robots shred the jellyfish and remove the remains. While this is the fastest and easiest solution (after natural predators), it is also the most expensive, for obvious reasons.

Ask me anything

Explore related questions