A Black Page in Cyprus’ History: The Coup That Opened the Gates to Tragedy

Every nation has its black pages in history. For Cyprus, there are many — but none as defining, as haunting, as the one commemorated today. It was not merely democracy that was executed on this day. It was the identity, the history, and the soul of Hellenism on the island that were placed against the wall. Since then, half of the homeland — and half of the nation’s spirit — has remained lost.

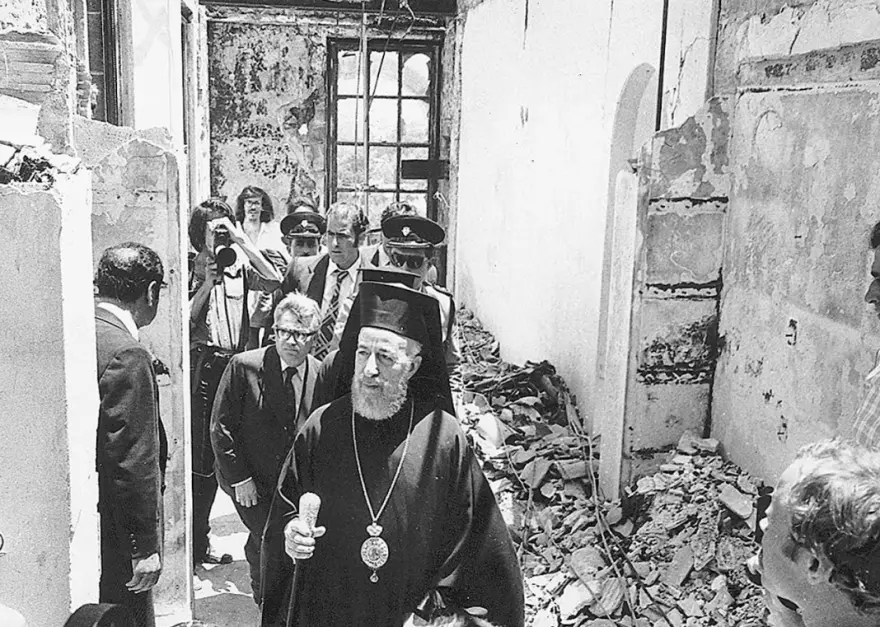

On this day, darkness fell. Not from a foreign invader — that came five days later — but from within. From the so-called “national centre” itself, which, through the force of arms, overthrew President Archbishop Makarios and installed a puppet of the Athenian junta. The coup against Makarios did not come out of nowhere; it was the culmination of a prolonged and dangerous confrontation that had simmered for years.

Flirting with Destruction

The 1960s were a turbulent decade. The independence granted through the Zurich-London Agreements satisfied neither of Cyprus’ two main communities. Greek Cypriots believed the constitution created a dysfunctional state. Turkish Cypriots, though officially a minority, had expansive rights, allowing them to paralyze government functions.

Archbishop Makarios, the Republic’s first president, attempted to walk a tightrope between nationalism and realism. But his vision of a gradually independent Cyprus — free from control by Greece — enraged hardline unionists who viewed any deviation from Enosis (union with Greece) as treason. Tensions with unionist factions and elements within the Greek military presence on the island, including ELDYK officers, were evident as early as 1964.

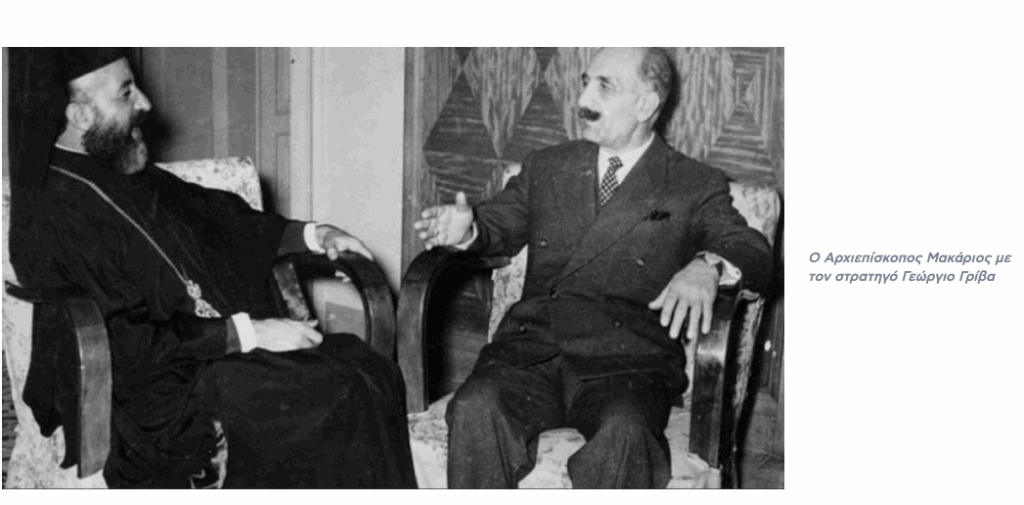

In 1971, General Georgios Grivas returned secretly to Cyprus and founded the terrorist organization EOKA B. Backed by the Greek junta, the organization targeted Makarios supporters, assassinated political opponents, and sowed fear. Meanwhile, pro-Makarios forces — though officially in control — sometimes operated as a parallel state themselves, exacerbating the instability.

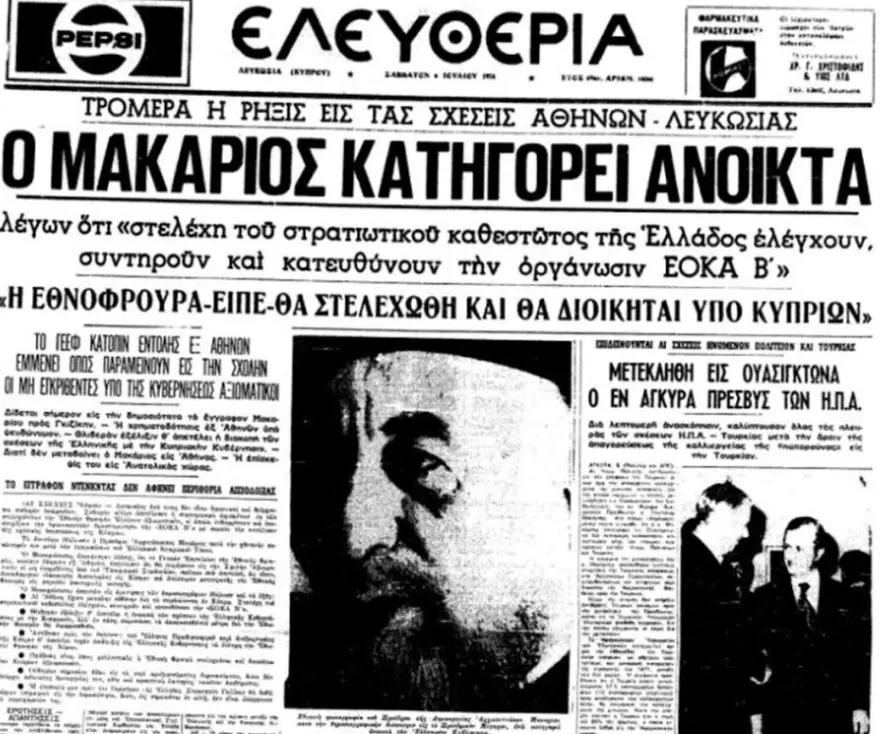

The Letter That Foretold Disaster

On 2 July 1974, Archbishop Makarios addressed a letter to Greek President General Gizikis, openly accusing the junta of undermining Cypriot independence. It was a historic warning — and a cry for help — that went unheeded.

“The root of evil,” Makarios wrote, “reaches all the way to Athens… where the tree of evil is fed, and grows, and bears bitter fruit.”

Makarios outlined the illegal support of EOKA B by Greek officers, the subversion of the Cypriot National Guard, and the steady erosion of Cypriot sovereignty. He condemned the Greek military regime for sponsoring violence and political assassinations, and demanded the withdrawal of Greek officers from the National Guard. His final plea was simple yet defiant: “I am not a prefect appointed by Athens. I am the elected leader of a large part of Hellenism.”

The Coup

At 8:15 a.m. on Monday, 15 July 1974, tanks of the National Guard surrounded the Presidential Palace in Nicosia. In a chilling broadcast, the junta’s voice declared:

“Makarios is dead. Familiar is the voice you hear.”

The signal to execute the coup had been coded: “Alexander has entered a clinic.” At that moment, Makarios was welcoming a group of Greek children from Egypt. He barely escaped with his life, fleeing the palace through a window under fire, and ultimately finding temporary refuge in Paphos — where he heard news of his own “death” broadcasted.

The coup plotters, led by Nikos Samson and backed by Athens, believed they had succeeded. General Ioannidis, the Greek junta leader, had told Samson:

“Nikolaki, I want the head of Muskos” (Makarios’ surname).

Though democracy was abolished, the coup failed to fully conso

lidate power. But it handed Turkey the pretext it was seeking.

The Invasion

On 17 July 1974, Turkish Prime Minister Bülent Ecevit sent a letter to the United States and Britain, citing the coup and the endangerment of Turkish Cypriots:

“The violation of the constitutional order in Cyprus poses an immediate danger… Turkey cannot remain impassive.”

When Britain declined to intervene, Turkey acted alone. On 20 July 1974, Operation Attila I was launched.

And the rest is bitter history: Invasion. Partition. Occupation. Ethnic cleansing. A de facto divided island. 51 years of loss.

The Greek and Greek Cypriot responses were chaotic. The coup regime collapsed. Nikos Samson, ridiculed as a “seven-day president”, handed over power to House Speaker Glafkos Clerides on 23 July, the same day the Athens junta fell.

Permanent Division

Half a century later, 15 July remains a scar — not just a memory. It still divides Cypriots: Macarians and Grivists, left and right, coup supporters and opponents. Each side maintains its narrative. Many accept that the main blame lies with the junta of Ioannidis. But that doesn’t absolve the Cypriots who willingly played their part: officers, Church figures, paramilitaries, journalists.

The reports by the Greek Parliament and the Cypriot House of Representatives remain filed and forgotten. Few were held accountable. Some perpetrators were rewarded. Others sheltered under the “olive branch” Makarios later extended, for the sake of unity.

July 15 is a day of national shame.

The betrayal of the coup is not undone with eulogies, symbolic ceremonies, or vague references to “mistakes.”

No one denies this day opened the gates to invasion, occupation, and displacement.

History does not punish.

But it does not forgive when we forget.

Sirens and Silence

At 8:15 a.m. today, sirens wailed once again across Cyprus. As every year, they marked the moment the tanks rolled in. At the Cemetery of Saints Constantine and Helen in Nicosia, a service was held for the fallen — both those who resisted and those who obeyed.

Later, President Nicos Christodoulides will travel to New York for a new round of informal talks convened by the UN Secretary-General. But hopes are dim. Turkey continues to demand a two-state solution, a proposal entirely outside the agreed framework for reunification.

The legacy of 15 July 1974 is not only the occupation of 37% of the island — but also the occupation of the national conscience.

Let this day not divide us further, but unite us in remembrance, responsibility, and resolve.

Lest we forget.

Ask me anything

Explore related questions