More than 100,000 objects and countless documents narrate the official history of Tatoi, bridging two centuries. Known and unknown items — even those forgotten or lost for years — from key moments in the lives of the royal families, archival remains and diaries, personal belongings, photographs, and memorabilia bring to life different chapters of Greece’s history and its diplomatic relations, while also revealing lesser-known aspects of the history of art and fashion.

As Minister of Culture Lina Mendoni emphasized during the presentation of the digitized collections of Tatoi: “The vast majority of the objects were found piled up in extremely poor conditions.” She added that most of them were unknown to the public, meaning that countless stories are now being brought to light thanks to their digital accessibility.

The Royal Dress

Among the countless objects found in forgotten corners of the former royal residences, many stand out for their historical significance. These are showcased in the “Stories” section of the Tatoi Collections website, which, as the minister noted,

“serves as a precursor to the 2026 opening of the restored palace complex and the main museum exhibitions to the public.”

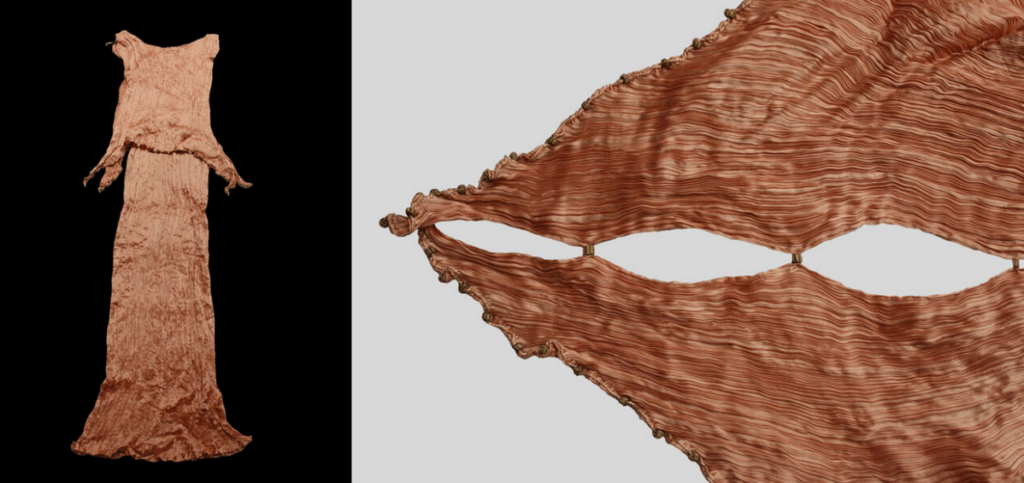

Imagine ministry staff opening a box containing an invaluable treasure: the ethereal Delphos dress, created as an homage to the Charioteer of Delphi. They were likely awed by its refined aesthetic, pleats, and the exceptional quality of this evening gown designed by the artist Mariano Fortuny. The garment stands out for its unique salmon-pink hue, its theatrical design, its silky texture, and the label from one of Florence’s most famous art ateliers.

What makes Fortuny’s creation — once owned by Queen Frederica and Queen Sophia — extraordinary is that it influenced the entire history of art and fashion through its singularity.

Mario Fortuny was not merely a fashion designer but also a painter, engraver, photographer, stage designer, pioneer in theatrical lighting, furniture and lamp designer, and inventor. His family shaped Spain’s artistic course in the late 19th century — his father, Mariano Fortuny y Marsal, was one of the country’s most important painters, and his mother, Cecilia de Madrazo, descended from a long line of directors of the Prado Museum.

When Fortuny designed this dress in 1907, as the Tatoi Collections website explains, it was revolutionary — women still wore tightly fitted, corseted gowns at the time.

Liberating women from such constraints and allowing them to feel more sensual, the Delphos was initially considered daring. Among the first to wear it were French actress Sarah Bernhardt, American dancer Isadora Duncan, and American socialite and art collector Peggy Guggenheim. As corsets fell out of fashion and softer silhouettes emerged, the Delphos became a hallmark of avant-garde aristocracy and was even referenced in the novels of Marcel Proust.

By wearing Fortuny’s Delphos — inspired by the Charioteer of Delphi — Queen Frederica broke from the stiffness of traditional royal gowns, setting her own quietly revolutionary style.

The gown’s intricate decoration featured Murano glass beads. The silk was repeatedly dipped in dyes crafted by Fortuny himself, ensuring that each piece had a unique color. The salmon-pink hue of this specific gown was made especially for Frederica, and later Sophia — making it a precious artifact in the history of European fashion and art.

It is no coincidence that the award-winning costume designer of Downton Abbey used a blue Delphos gown to accurately capture the refined tastes of the 1920s aristocracy.

King George I’s Key

The story of the dress is just one among countless others found in the digital collections, presented in detail by Maria-Xeni Garezou, Deputy Director of the Directorate for the Management of the National Archive of Monuments, during a special seminar at the Benaki Museum. She described the multi-stage process that included cataloguing, documentation, and digitization — part of the broader, ambitious “Tatoi Project,” a flagship initiative of the Greek government.

“The overall plan aims to highlight the estate as a site of historical memory, culture, education, environmental awareness, and recreation — within the restored and protected natural landscape — respecting its unique identity and ensuring its long-term sustainability,”

explained Minister Mendoni.

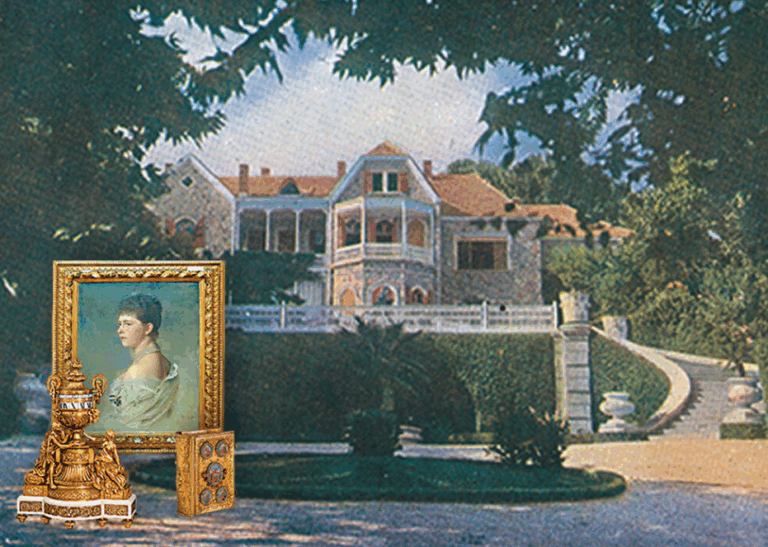

Under this framework, a small yet deeply symbolic item — a gilded key bearing the initials of King George I, who purchased the Tatoi estate in 1872 — “unlocks not only Tatoi but also a century of Greek history,” as Mendoni emphasized. The key adorns the cover of the special volume Unlocking the Tatoi Collections.

It is similar to the chamberlain’s keys commissioned by King George I of Greece, who reigned from March 18, 1863, until his assassination in 1913, marking the rise of Greece’s royal dynasty. Born Prince William of Denmark, George arrived in a Greece eager to become European, embracing its ancient heritage. He sailed from Copenhagen carrying this symbolic key, his monogram marking his transition to a new Hellenic identity, arriving in the newly neoclassical Athens shaped under King Otto.

Elected king by the Greek National Assembly at just 17, George learned Greek and earned the trust of the people. His portraits, displayed in government buildings and public institutions, played a key role in solidifying his image. He even brought in German photographer Carl Boehringer to serve as court photographer — his family portraits, found in the archives, include those of George I and his wife, Olga Constantinovna of Russia.

Their descendants — Constantine I (who married Sophia of Prussia), and later George II, Alexander, and Paul (who married Frederica) — anchored the ties between the Greek, German, and Russian royal families.

The “Narrative Plates”

King George’s marriage to Queen Olga was a deliberate move to strengthen Greece’s Orthodox identity — something reflected in the treasures found at Tatoi. Among them are the famous “narrative plates,” a hallmark of the European Renaissance tradition. Originating from the Italian maiolica style, these ceramic pieces feature a white tin glaze and vividly painted historical or mythological scenes, often commemorating family events like weddings or births.

Several such items were discovered at Tatoi, including commemorative dishes for the 1867 royal wedding of George and Olga, a plate with their portraits, and another celebrating the annexation of Thessaly and Arta to Greece.

Queen Olga’s Russian heritage is further evident in the Fabergé collection — ornate frames, vodka cups, boxes, goblets, and desk accessories adorned with precious stones, created by artisans of the renowned Russian house that supplied royal families across Europe. Her personal seal, bearing a naval motif, reflects her honorary role as admiral of the navy.

The Endless Journeys

George and Olga had eight children, including Alexandra, who married Grand Duke Paul of Russia but tragically died in childbirth. The family gathered at royal palaces across Europe — particularly in Denmark — where they enjoyed leisure activities like cycling. Olga frequently traveled to Russia via the Black Sea.

Her albums, discovered in the Tatoi archives, along with the memoirs of her son Christopher, describe journeys aboard the imperial train to St. Petersburg.

As royal travel became increasingly popular, luxury luggage — including leather trunks and vanity cases by Tiffany, Cartier, and Gucci — evolved from practical necessities into works of art, epitomizing sophistication and refinement.

Of exceptional aesthetic value and rarity are also the jewel and cosmetic cases, which over the years have become rare heirlooms, found among the collection’s objects, bearing the distinctive royal monograms.

As ministry officials revealed during the presentation, thousands of items have been officially designated as “monuments.”

For, as the Minister of Culture emphasized, “through the various thematic categories dictated by the very nature of the artifacts, the specialized scientists working on the cataloguing and documentation of the Tatoi Collections perceptively and vividly highlight the many facets of the palimpsest of historical memory.”

This is evident not only from the texts accompanying the special edition “Unlocking the Tatoi Collections,” but also from the entirety of the catalogued material and the operation of the dedicated website featuring the digitized collections — now publicly accessible and thus constituting a democratic heritage belonging to all.

Ask me anything

Explore related questions