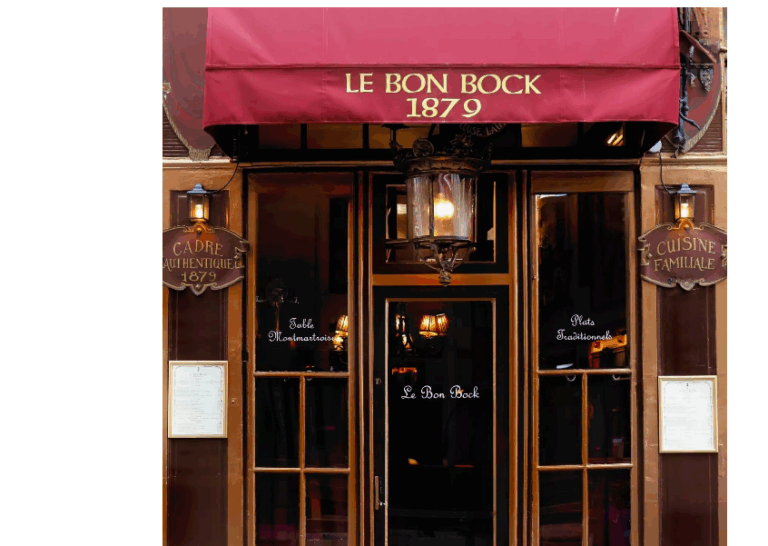

Founded in 1879, has been reborn today thanks to two visionaries who value authenticity over trends. Cantina visited, candlelight flickering, spoke with the creators of its new chapter, and wandered through a Paris that continues to hum quietly.

In an era of fast food, staged experiences, and trend-driven restaurants, Le Bon Bock feels almost miraculous—not because it tries to impress, but because it doesn’t try at all. Since 1879, at the heart of Montmartre, it has quietly written its story without following fashion. And that is its magic.

Cantina crossed its threshold on an autumn evening—not to dine “like a Parisian,” but to experience life as Parisians truly live: unposed, unfiltered, with a glass of wine in hand and conversations that start spontaneously and linger late.

Le Bon Bock is more than a restaurant. It is a living monument to the French art de vivre—that subtle, nearly ineffable sense that blends elegance with everyday poetry. It is a place where time pauses, yet life continues, naturally, humanly, almost conspiratorially.

“Hospitality here is not a profession,” said Adrien Chiche, dining room manager and partner in the venture. “It’s a way of life.” And it was clear immediately: the atmosphere is genuine, not staged; warmth is spontaneous, not served. Nearby, a Parisian couple discussed books. In another corner, tourists shared plates and laughter. At the bar, a regular elder sipped his glass, the same every evening for 30 years.

A Table Full of Art, Companionship, and a Touch of Absinthe

Le Bon Bock’s history is inseparable from Paris’s artistic soul. On its walls hang, sometimes timidly, sometimes proudly, the shadows of Manet, Toulouse-Lautrec, Van Gogh, and Apollinaire. All passed through here, drinking, talking, writing, painting. The space was a hub for Belle Époque intellectuals and bohemians, who gathered around a glass of absinthe to celebrate, flirt, and philosophize.

Even the name “Bon Bock” references that era, specifically Édouard Manet’s painting Le Bon Bock (1873), depicting a solitary drinker whose serene presence embodies the relaxed, communal, deeply human spirit of Parisian brasseries.

Today, Benjamin Moréel and Christopher Prêchez, two young restaurateurs with historical sensitivity and culinary vision, have not sought to “modernize” Le Bon Bock. As they told us: “We don’t want to create another ‘concept’ for Paris. We want to protect a real place. Le Bon Bock is like an old book: you don’t rewrite it. You read it carefully, dust it off, and let others love it as it is.”

Under chef Salim Soilah, the cuisine remains deeply bistro, authentic, generous, yet never lazy. We were served œufs mimosa, pistachio-crusted pâté, snails, gratin quenelles with crayfish, boeuf bourguignon with coquillettes, and finished with baba au rhum with fresh crème chantilly. Every dish is honest, handmade, crafted with care—not to impress, but to honor.

A Return to the Essential

From candlelight to the music that some nights drifts from the back room, Le Bon Bock evokes inner calm. There is no noise, only companionship. No posing, only authenticity. No chaos, only music.

“You don’t come here to see and be seen,” Christopher says. “You come to share.” That is, ultimately, its beauty. Le Bon Bock is not fashion; it is habit. It is one of those places that, when you find it, feels like it has been waiting for you. And that is why you return.

Ask me anything

Explore related questions