These divisions have cost the country dearly: rivers of blood, national defeats, and lasting scars that never quite heal, even if they fade with time.

It’s not a matter of “Greek DNA” or cultural destiny. Many nations have gone through civil conflicts — from the American Civil War to Switzerland’s brief internal war in 1847. Yet, in Greece — the “land of parallel monologues,” as poet Giorgos Seferis once said — quarrels have long been a national tradition.

Even in the age of the Internet, battles have moved to keyboards and screens. Social media overflows with anger, misinformation, and toxicity. Minor issues turn into “wars,” and arguments easily become national divides.

For example, consider the heated debate over protecting the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier — a symbol of unity that somehow became a new source of polarization.

And how is it possible that in 2025 people still die in rural Greece over blood feuds, while entire communities live in fear?

From Ancient Greece…

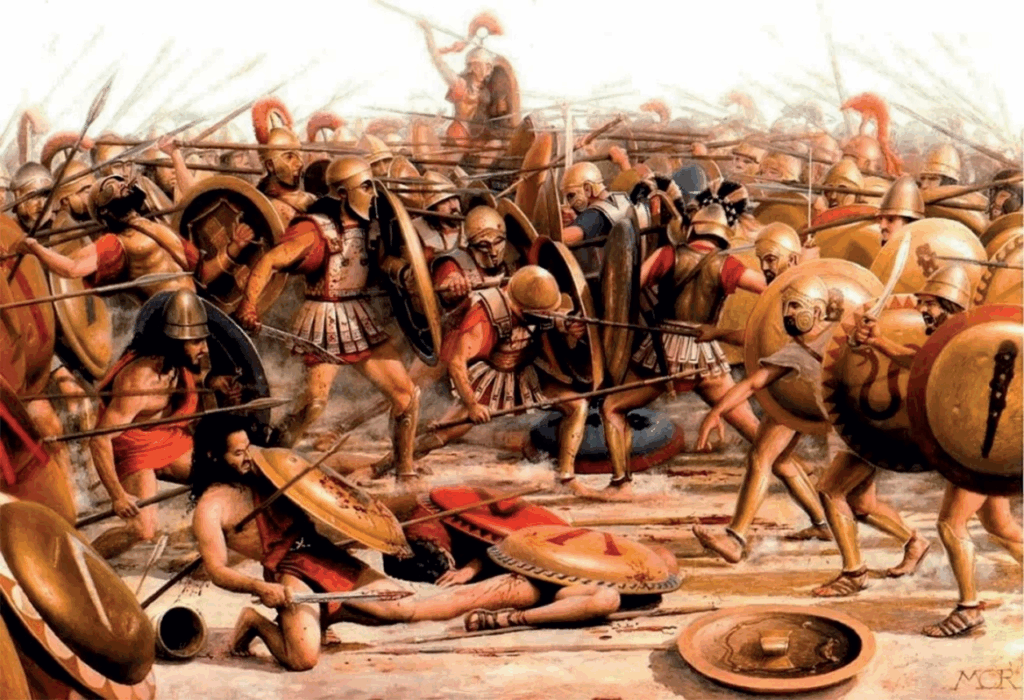

Ever since ancient times, when the land was divided into city-states, Greek history has been full of civil wars — despite the ideal of a shared language, faith, and ancestry.

Alongside glorious victories like Marathon, Salamis, and Thermopylae, there were countless Greek-on-Greek battles: the Peloponnesian War between Athens and Sparta (431–404 BC), the Messenian Wars, the Lelantine War in Euboea, and many others.

…To the Revolution of 1821

Even during the War of Independence against Ottoman rule, Greeks fought one another. Two bloody civil wars broke out (1823–1825), dividing revolutionaries into factions over power and spoils.

Theodoros Kolokotronis was even jailed, and Odysseas Androutsos was murdered by fellow Greeks. “The violence,” one chronicler wrote, “was such that not even the Turks behaved so brutally.”

When Governor Ioannis Kapodistrias arrived in 1828, Greece was in ruins. His assassination in 1831 by the Mavromichalis brothers plunged the new nation into chaos again.

The “Hat Riots” of 1859

In 1859, a bizarre episode known as the Skiadika erupted in Athens — a riot over straw hats made on the island of Sifnos! What began as a patriotic gesture to support Greek products turned into street battles between students and the police.

The “June Events” of 1863

After King Otto was overthrown, two factions — the “Plains” and the “Mountains” — fought violently for power. The fighting in Athens lasted three days, leaving hundreds dead before foreign powers intervened.

Language Wars

In 1901, the Evangelika riots broke out after a newspaper published the Gospels in modern Greek. Students, priests, and nationalists saw this as blasphemy. Eleven people were killed in the protests.

Just two years later, riots known as the Oresteiaka followed the performance of Aeschylus’s Oresteia translated into the vernacular. Even plays sparked bloodshed.

The National Schism (1912–1922)

The bitter conflict between Prime Minister Eleftherios Venizelos and King Constantine I over Greece’s stance in World War I split the nation in two: the Venizelists and the Royalists.

This deep political and social divide lasted decades and ultimately led to the Asia Minor Disaster in 1922.

The Civil War (1945–1949)

After World War II, Greece plunged into a brutal civil war between communist forces (the Democratic Army) and the government, supported by Britain and the U.S.

It left more than 50,000 dead and tens of thousands of refugees. The wounds of that conflict scarred the nation for generations, only starting to heal after the fall of the military junta in 1974.

The Tumultuous 1960s

The 1960s were marked by political upheaval, street protests, and assassinations, such as that of MP Grigoris Lambrakis in 1963.

The monarchy’s interference in politics and the 1965 “Apostasy” crisis paved the way for the 1967–1974 dictatorship — another dark chapter in Greek history.

A New Cycle

Since the restoration of democracy in 1974, Greece has remained within democratic boundaries, despite fierce debates and crises — from the debt crisis to the “Indignant” movement of 2011.

Still, the tendency to divide into camps persists. Perhaps, as Nikos Kazantzakis wrote, “Greece survives through a series of miracles.” But miracles, as history shows, don’t last forever.

Ask me anything

Explore related questions