Speaking for the first time openly about all his political comrades, as well as his governmental partners, Alexis Tsipras in his book Ithaca seeks to highlight behaviors, mistakes, weaknesses and personal strategies in his political and party environment through a series of events that start from his first days as leader of SYRIZA–PS and reach up to his resignation.

Excluding the late Alekos Flambouraris—who had guided him since his student years as his political mentor—the former Prime Minister sheds light on unseen aspects of his governance, while also recounting what unfolded from time to time behind party doors, in an attempt to give a panoramic assessment of the “assault on the heavens,” which nevertheless cost him dearly—because of his comrades—on quite a few occasions, as he implies in many parts. Without precedent, however, Alexis Tsipras vividly revives what marked the country’s recent history over the last decade, letting “the facts speak” and without intentionally resorting to positive or negative labels, although in many cases the associations arise naturally for readers, without him attempting to overturn them.

Yanis and the… vouchers

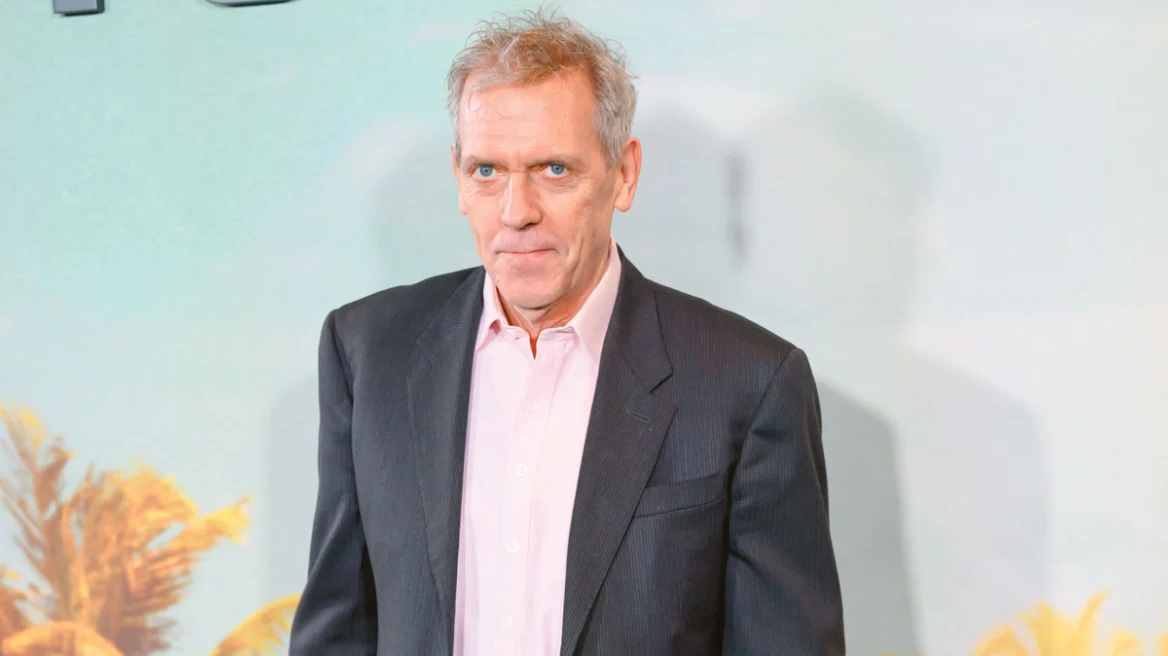

One of the faces that returns often in the pages of Ithaca is that of Yanis Varoufakis, whom Tsipras chose as Finance Minister of the “first-time left” government. “For the Ministry of Finance, I had initially spoken with Giannis Dragasakis. I had made him the proposal long before our election victory, nearly six months earlier, but he did not accept,” he notes. Although Varoufakis was not the former Prime Minister’s first choice for the “electric chair” of the Finance Ministry, at first he seemed the most suitable, since Tsipras had planned a high-intensity negotiation with the institutions. As he says, “in any case, Varoufakis, when I chose him as Minister, was not a supporter of exiting the euro. And I wanted an honest agreement within the euro. We had emphasized this repeatedly. But on the other hand, we did not hide that we sought radical changes in Europe. We wanted to halt the imposition of neoliberal economic irrationality, not only in Greece but across the continent. To end austerity policies.”

However, as the negotiation progressed, Varoufakis’s strategy began to unfold, along with the apparent failure of his tactics, with Tsipras describing that “Varoufakis was not simply an economist with theories, he was a man with such immense self-confidence that he wanted, at all costs, to prove that the theories he embraced were correct. He wanted, in other words, to test his mathematical models and game-theory ideas, which he taught in academic lecture halls, on the battlefield. In short, there was in him a scientific obsession, a willingness to go all the way, even if that would cause the collapse of our plan, the collapse of the government or even of the country.”

As for “Varoufakis’s plan,” Tsipras recounts: “He said we would print some coupons instead of giving money to pensioners and employees; we would give coupons, and with them they could buy goods and services. When I heard it, I didn’t know whether to cry or laugh. I reacted: ‘Are you out of your mind? How will we give coupons instead of pensions? We won’t last a single day. Which pensioner will accept coupons instead of a pension?’ Then he began telling me there was an alternative—not printing coupons but doing everything electronically via mobile phones. Pensioners transacting via mobile phones, in 2015! With that level of sloppiness, for me the discussion ended,” Tsipras concludes.

The four references to Polakis

Among the sharpest references the former Prime Minister makes in his book are the four mentions (more than anyone else) of SYRIZA-PS MP for Chania, Pavlos Polakis. Regarding the vaccine issue, he admits he considered expelling him. “Several had recommended that I expel him. His divergence from our line on such a sensitive issue indeed constituted a very serious misstep. Ultimately, although I confess I thought long and hard about it, I did not make such a decision.

I tried to convince him that, in public-health terms, questioning vaccines posed serious dangers to life and, in political terms, harmed our common effort, provoked harsh attacks against us, and cast doubt on the sincerity of our stance,” he explains. And concerning the formation of the party lists for the 2023 elections, Tsipras speaks of “a blackmailing demand” by his party comrade.

However, “there was no way I would avoid taking responsibility and turn my back on Polakis, despite the mistake he had made. In politics, as in life, one can hardly escape one’s character,” Tsipras says regarding Polakis’s political attack on ND MEP Stelios Kympouropoulos. Additionally, referencing the “hit list” affair—when Polakis posted an image targeting a number of judges and journalists on social media—Tsipras does not hide his anger.

The “institutionally consistent” Kammenos

On the opposite end, he evaluates the stance of former Defence Minister Panos Kammenos as honorable, even if their cooperation occurred almost… accidentally, as Tsipras recounts. Despite the ANEL leader’s strong anti-memorandum rhetoric, an elevator ride is, according to Tsipras, what led to their governmental partnership—with Kammenos beating Stavros Theodorakis “to the punch.”

As Tsipras describes, after SYRIZA came to power in January 2015, “I asked to meet with Stavros Theodorakis, as leader of The River, and with Panos Kammenos, who led the Independent Greeks. The next day, Kammenos came first to my office at Koumoundourou. We had previously had some contact and discussions—mainly Pappas spoke with him, and I had spoken with him once or twice. A few months earlier, on 14 October 2014, we had officially met in my office at the Parliament about ANEL’s proposal on non-performing loans.” “So he came to Koumoundourou earlier than Theodorakis, even a few minutes ahead of our scheduled appointment, and outside SYRIZA’s offices he made statements to TV crews essentially announcing the imminent agreement before even meeting me,” Tsipras says, before going on to praise his coalition partner.

“He went up to the seventh floor, we took the customary photos, and when the door closed he told me: ‘I want the Defence Ministry and I won’t set any conditions. I don’t want to be Deputy Prime Minister. I want the Defence Ministry because that has always been my dream. I want to take part in this effort. Together we will create a new national unity. You will be Aris Velouchiotis and I will be Napoleon Zervas…’” Tsipras continues, adding that “beyond his usual exaggerations, which I expected, I admit his stance surprised me. I expected him to set specific terms and demands for joining the government. Instead, his approach was different, almost unexpected, and that, I confess, pleasantly surprised me.”

Moreover, “the truth is that, despite his occasional unorthodox—by political-leader standards—behavior, which often caused embarrassment or irritation both domestically and abroad, Panos Kammenos stood with institutional consistency by me and supported the functioning of our government without creating problems in its everyday cohesion. He did not impose unreasonable terms, he did not undermine us, he did not pull the rug from under our feet,” Tsipras concludes.

The “unexpected” 13–0 of Pappas

Tsipras appears more decisive in retrospect about his close friend and former trusted collaborator Nikos Pappas, following Pappas’s conviction in the TV-licensing case. “It was clear that I had to weigh my decisions carefully. I contacted Nikos immediately, waiting to see what stance he would take. Clearly hurt by the decision, he showed no inclination to raise the issue of resigning, stepping aside temporarily, or even leaving open the possibility of withdrawing from the front line ahead of elections. Nor did I on my part initiate such a discussion,” Tsipras writes. However, “in retrospect, I believe I should have asked him to make things easier—primarily for the party but also for himself—by withdrawing his candidacy. And this is because he had shown unacceptable carelessness throughout the process,” the former Prime Minister concludes in self-criticism.

Kasselakis as a tragicomic figure

Alexis Tsipras also refers very vividly to his successor in the party leadership, Stefanos Kasselakis. As the former Prime Minister notes, “the picture at the beginning was somewhat tragicomic. It was as if we were living through a remake of the famous Italian comedy Viva la libertà by Roberto Andò, where the leader of Italy’s Centre-Left Party, played by Toni Servillo, suffers a depressive crisis and mysteriously disappears. Things take an unexpected turn when his assistant discovers his twin brother and, in his desperation, presents him as the real party leader — even though he knows nothing about the party or politics, and that’s where a series of absurd events begin. Something like that happened with the SYRIZA base which, in its despair, elected Stefanos. And all of us tried at first, respecting the democratic verdict, to support him and teach him the basics, so that he could at least stand on his feet and we could avoid collective humiliation,” Tsipras concludes.

Pavlopoulos since… 2008

The former Prime Minister speaks warmly of former President of the Republic Prokopis Pavlopoulos, whom he had met in December 2008 after the murder of Grigoropoulos. “During those hours he was in constant, daily communication with me with a sincere intention to avoid the worst, namely the escalation of violence,” describes Tsipras. “That’s when a relationship of honesty, mutual respect and genuine communication began to form between us,” he continues — a relationship that “over time was destined to play a decisive role in my decision to propose him for the office of President of the Republic.”

Criticism of the referendum to G.A.P., “speechless” on Karamanlis

There are also many references in Ithaca to former Prime Minister George Papandreou, who governed during SYRIZA’s rise. It all begins at the PASOK Congress, when Alexis Tsipras was invited as a speaker — a move he later confesses he believed was a trap. “What Papandreou’s ploy at the PASOK Congress failed to achieve with the proposal of post-election cooperation, which was rejected, was achieved by December and the shocking events after the murder of Alexandros Grigoropoulos,” Tsipras argues, adding that the invitation to speak at the Congress was “intended to ‘expose’ me.”

Speaking critically about Papandreou and his attempt at a referendum, he recalls: “In Parliament, without knowing all the backstage consultations taking place at the time, I took the floor and challenged Papandreou to hold a referendum, so that the Greek people would either ratify or reject the decision. In the end, at the critical crossroads, he chose the seemingly safer path, the one that would mathematically lead to his political destruction. He decided to ratify the IMF agreement with only the government’s 160-seat majority. Neither with an enhanced majority of 180 MPs nor through a referendum. Both carried the risk of defeat, but not the certainty of collapse,” Tsipras comments meaningfully — while avoiding any harsh reference to former Prime Minister Kostas Karamanlis.

Reservations and… Theodorakis

Although the former Prime Minister acknowledges that the leader of To Potami, Stavros Theodorakis, was familiar to him due to their televised interviews, he believed that a government partnership would clash with ideological and political differences if it ever came to pass.

Still, he invited him in January 2015 to SYRIZA’s headquarters a few minutes after Panos Kammenos, exploring the possibility of cooperation. After informing Kammenos of such a prospect, Tsipras recalls: “I’m thinking of proposing to Theodorakis that he join the government,” and reports Kammenos’s reply: “Don’t bring him, he’ll tear us apart; he’ll give everything away to the outsiders.” According to Tsipras’ account, “Stavros Theodorakis walked through the main entrance of the Koumoundourou offices. He entered without giving statements and began to climb the stairs. I could not imagine how important that detail would prove. With Theodorakis nothing was predictable — quite the opposite. Kammenos and Theodorakis operated in completely different political and aesthetic wavelengths. Yet I believed that after the elections things could change.”

“There had been some exploratory contacts to arrange the meeting, though in the dominant dividing line of the time, Theodorakis and To Potami were not counted among the so-called anti-memorandum forces. A large part of SYRIZA intensely disliked him, though some believed his participation in government would help. And I had generally good relations with him from his journalism days when I had given him a few interesting interviews. However, I admit I was not fully convinced we could cooperate harmoniously, because the climate was polarized around the Memorandum vs. Anti-Memorandum divide, and this would complicate our moves,” Tsipras adds, implicitly foreshadowing the impossibility of collaboration.

The “Narcissus” Zoe

“A characteristic case of such self-destructive intransigence was that of Zoe Konstantopoulou,” Tsipras writes in Ithaca about the former Speaker of Parliament. He comments that “managing her was one of the most painful experiences of that period,” admitting he had already regretted proposing her for the position “in an attempt to project renewal and combativeness. A young and dynamic woman in a role typically reserved for political retirees — that’s what I thought when I decided to nominate her.”

“However, her stance was consistently confrontational and obstructionist. From the outset she opposed any idea of an Agreement, without feeling the slightest need to present an alternative proposal,” Tsipras continues, portraying her as inflexible. “When I called on her to discuss realistic alternatives in the event of a full rupture with our partners, she replied with disarming vagueness: ‘We will go to the UN.’ And when, almost in despair, I asked, ‘And if we go, what exactly will change? Won’t the public finances and banks have already collapsed?’, she stubbornly repeated: ‘The debt is odious; we must appeal to the UN.’ She insisted on her own strictly one-dimensional understanding of the problem, completely ignoring the country’s urgent needs and the political challenges of the moment,” he adds.

The double refusal of Achtsioglou – Haritsis

The former Prime Minister received a double, and rather negative, surprise after the electoral collapse of 2023 in his attempt to appoint a successor — first Effie Achtsioglou, then Alexis Haritsis. Regarding the former Labour Minister, “she told me that the idea of leading SYRIZA had never crossed her mind and that she felt unready for such a burden. She also mentioned her family and the difficulties she would face balancing the role’s demands with the needs of her young child,” Tsipras recalls. He adds that “her stance surprised me. Where I saw a great opportunity, she saw problems.”

He then turned to Alexis Haritsis. However, “upon hearing my decision to leave and even more so my proposal that he run, he darkened. He told me he did not feel ready to take on such a heavy burden. And he asked me not to resign,” Tsipras remembers, concluding: “After that meeting too, the options were narrowing.”

The “exit supporter” Lafazanis

Referring to the former Speaker of Parliament, Alexis Tsipras groups her together with the “supporters of exiting” the euro, such as former Minister and head of the “Left Platform,” Panagiotis Lafazanis. As Alexis Tsipras recounts:

“After the agreement, Konstantopoulou, in order to oppose the central choices of the government, turned herself into a dissenting voice. She aligned with the supporters of exit from the euro and Europe — Lafazanis and those who left with him — taking advantage of her institutional role as Speaker of Parliament, to which she had been elected at my own proposal. Instead of ensuring the smooth functioning of Parliament, she chose to actively obstruct procedures, causing delays in crucial votes. Thus unfolded events that offend any notion of seriousness, with exhausted MPs sleeping on the benches because the sessions were deliberately starting at midnight. She herself intentionally delayed taking the Speaker’s seat, resulting in procedures lasting until the next morning.”

In this context, “the culmination of her unpredictable and obsessive behavior came later, in August, during the voting procedures for the loan agreement. The constant postponement, the artificial delays, the unusual procedural strictness to the point of excess, revealed an immature political attitude that undermined the role she was meant to serve. Instead of being an institutional guarantor, she had turned into an agent of Parliament’s humiliation. She would deliberately exhaust and keep the House awake until six in the morning, without serving any institutional purpose other than the need to express her disagreement in a theatrical way,” the former Prime Minister recalls about those dramatic moments, concluding that “unfortunately, politics and the Left attract narcissists like light attracts insects.”

The underestimation of the “Umbrella”

At the same time, the former Prime Minister does not hold back from referring to historical SYRIZA figures, even though some of them — such as Nikos Voutsis — had supported his rise to party leadership. However, the 2019 defeat created new intra-party dynamics, and “so in December 2020, Voutsis, Tsakalotos, Vitsas, Papadimoulis, Lamprou, and Dritsas visited me in my office with full formality. This large delegation came to inform me that a new faction was being formed, which they named ‘Umbrella.’”

“What was the political or ideological basis of this grouping? One and only: their opposition to the transformation of SYRIZA into a modern, mass, democratic, and open party of the Left. And their opposition to me, who supported this transformation,” the former Prime Minister stresses.

He adds: “At the time, I judged it a move without particular political weight, one that could not halt our strategy. Deep inside, I was certain that when the time for the Congress arrived, the party members and the progressive public would take the transformation into their own hands. And nothing would be able to stop it.

“This was a correct assessment — but only in intra-party terms. What I underestimated was that these developments were not just internal matters irrelevant to society. They negatively affected the already burdened image of the party,” he concludes.

“Dimitra” and… Tsakalotos

Although Alexis Tsipras considers Euclid Tsakalotos the most suitable person to succeed Yanis Varoufakis as Finance Minister, nevertheless “New Democracy had in its hands an intra-party document that Tsakalotos had signed along with other Umbrella members, written long before the elections, when I had asked for serious proposals for our pre-election program. They had then proposed the idea of local currencies, which they considered so brilliant that they made it public,” Tsipras recounts.

“I remember I was truly enraged, mainly with Tsakalotos, but Andreas Xanthos ended up paying the price. It was probably the only time I ever spoke in such a harsh tone, especially to someone with a mild character like Andreas. But he happened to be in front of me at the moment I learned about it, and he took the hit. I even ended up shouting at him: ‘If you don’t want us to ever win elections again, if you want to undermine the party, say it clearly,’” he describes, believing that the parallel-currency proposal cost the party in the electoral outcome.

The “Members’ Initiative”

Against the “Umbrella” faction, other cadres mobilized under the banner of transforming SYRIZA, but with rhetoric and intra-party practices that did not particularly enthuse Alexis Tsipras.

“Opposing the ‘Umbrella’ a different bloc became active — led by figures like Pappas, Polakis, and Tzakri. Supposedly they were driven by support for the restart plan, but what actually motivated them was hostility toward the Umbrella. This conflict was not only political. It was a clash of culture and style that reached the party base. One side supported a party that was indeed closed, but serious and measured. The other proposed a more popular, hardline anti-right-wing stance, based mainly on anti-right rhetoric and denunciation. One side offered more rational argumentation, often difficult and elitist; the other spoke a more comprehensible language but projected an aggressive, often toxic tone, at a time when citizens wanted calm, not escalation. A comparison between Polakis and Tsakalotos perhaps best illustrates this difference in style and culture,” he notes.

The large “incomprehensible” image of SYRIZA

Looking back a decade later, Alexis Tsipras attempts to summarise in a few lines the broader atmosphere within SYRIZA during the negotiation period, describing the psychological and political distance between himself and his own party. Even for him:

“Some things in SYRIZA seemed incomprehensible. And I had not come from another planet — I was part of that world. I took part in party processes from the age of fifteen, spent hundreds, maybe thousands of hours of my life in them, yet there were moments when I could not understand how it was possible that they did not grasp the situation, the difficulties, our political line. It would be unfair to say they were not fighting. They were fighting, most of them, on the front line. They supported our political line, even if they didn’t fully understand it or disagreed with parts of it. Nevertheless, from the summer of 2015 onward, a grumbling, a negative attitude, an excessive tendency toward self-criticism weighed on the party’s atmosphere.

“I felt as if they believed we needed to constantly apologise for having won the elections again,” he says.

“Obviously, there were political reasons. The shift we were forced to make in our strategy naturally disoriented many. But since moral evaluations play a huge role on the Left, I sensed an underlying feeling of guilt in the party. Neoliberal austerity, compromises, policies we did not agree with but had to implement to save society and the country — these deprived many of sleep. I admit that at times I was among them, and perhaps that’s why I understood them so well. But understanding is one thing and justifying is another. I justified no hesitation — neither to myself nor to anyone else. I was the head of a team of dedicated people whom the people had entrusted with the heavy responsibility of saving the country,” he explains.

The “first time Left”

Regarding the composition of the “first time Left” government, the former Prime Minister concludes in retrospect that “the most serious problem was not their attire, but their statements before and after being sworn in. Before they even arrived at the Cabinet meeting, some of them must have already raised Greek bond spreads by at least one percentage point each. One was nationalizing services, another was rehiring the fired, another was expelling the Chinese from Piraeus. There prevailed the optimism of will and the absence of the pessimism of reason.”

Ask me anything

Explore related questions