Valeria Golino: A southern woman bridging two languages, two cinematic traditions, two lives

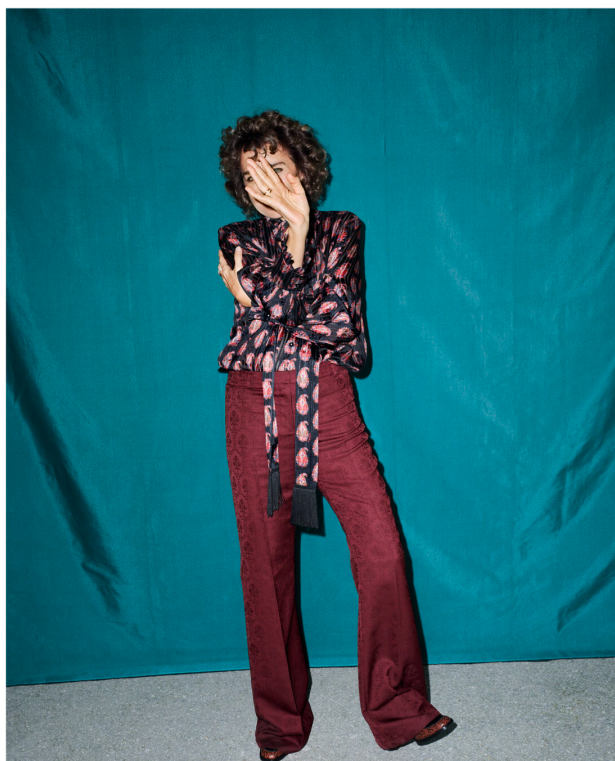

Four decades after her debut film and winning the Volpi Cup at the Venice Film Festival (“Storia d’amore,” 1986), Valeria Golino no longer cares about what others say. She fits only into one mold—her own—a fact she brilliantly proved at her appearance at the Marie Claire Power Trip. Cheerful and disarmingly honest, Valeria is a living legend of European cinema.

From Rain Man and major Hollywood productions to some of the most demanding roles in European and independent films, Golino carved her own unique path—one that earned her a second Volpi Cup in 2015 for Per amor vostro.

In recent years, however, this Italian-Greek star has moved beyond bringing others’ stories to life. She now chooses the stories she wants to tell. Behind the camera, she opens difficult, political conversations about euthanasia and scores a triumph with The Art of Joy, a TV adaptation of the iconic novel by Goliarda Sapienza. Meanwhile, she continues acting with the same energy she had in her twenties (most recently seen in season two of The Morning Show).

Valeria brought that youthful energy—a mix of determination and lightheartedness—to Athens, a city where she grew up and often returns, this time as a guest at the 7th Marie Claire Power Trip. Smiling and quick-witted, a woman who knows what she wants, she captivated audiences with her honesty and spirit. Speaking comfortably in three languages (Greek, English, and Italian), she discussed the beauty and the harshness of the South that shape us without us realizing it, the fear and courage it took to become a director, death as a political issue, motherhood beyond moral stereotypes, and the unique power of cinema to change things.

How has this dual heritage—your Italian and Greek sides—shaped you as an artist and actress?

I believe where we come from and where we spent our early years shapes us deeply: what our eyes have seen, what our ears have heard, the languages we speak, and the beauty around us. In the South—both Italy and Greece—we live surrounded by breathtaking beauty, so familiar that sometimes we fail to see it. We live in landscapes, cities, light, seas, and architecture that are unbelievably beautiful. But it’s not just the beauty. It’s also the harshness of the South, which has its own history, poetry, and past. Even when things are chaotic, that chaos has something alive and human. This mix of chaos and beauty—the Greece and Italy I know—has influenced me deeply. I’m proud to be a child of the South.

I didn’t grow up in an industry that encourages women to direct. It took time, experience, and inner work to dare.

You’ve made brave choices, never opting for safety in your collaborations. You’ve built a career both in American and European cinema—a rare feat. Would you say European cinema has more depth and maybe more “soul” than American?

Americans have made great cinema—perhaps less so in recent decades, in my opinion—but fantastic films still exist. They created much of cinema’s history. Europeans, on the other hand, make a different kind of cinema, partly because we have fewer resources. In Europe, the auteur cinema—the director’s personal vision—is still alive. The director’s signature matters a lot. In big American studios, things are more industrial. On television, for example, the writer is hugely important. The director remains important, but not in the same way as in Europe. I try not to fall into stereotypes like “we have soul, they don’t.” Great, profound cinema exists on both sides. They’re just different ecosystems.

You once said, “It’s nice to be an actor, but the person who makes all the decisions is the director.” Is that what finally led you behind the camera?

Yes, but it took me many years. I’ve been an actress since I was 16. I love my craft and still feel like an actress. It took time to gain the courage to say, “Now I will direct.” It wasn’t just about knowing the work—I knew I had taste and understood cinema. It was about confidence and how I saw myself. I think this relates directly to being a woman. I didn’t realize it then, but I understand now. I was afraid I wouldn’t be enough, that I wouldn’t have the right to stand as a director. I didn’t grow up in an industry that encourages women to direct. It took time, experience, and inner work to dare.

I believe cinema still carries the responsibility to open conversations on difficult topics and help change things. Maybe that’s its last great power: it can change your mind.

What changes when a woman sits in the director’s chair? Do you think people listen to and trust her as much as they do a man?

That’s an interesting question because you do have to work much harder to be heard. You need to find a language that is yours but also reaches others. That’s why working with good collaborators—men and women—you trust is so important. The director’s real power is to truly listen and use others’ talents. I’m very open to my collaborators’ ideas. I know their opinions, techniques, and artistry can become my strength. I’m not afraid to say, “What you said is better than what I thought.” That’s how the work gets better. But because you are gentle and want to listen, people might see you as weak or insecure. Yet, for me, listening is the opposite of weakness. It’s the most creative form of power.

In your second film as a director, Euforia, you tackle euthanasia. How did you come to such a difficult subject?

I did it for many reasons. Legally, as a citizen, I was deeply concerned about euthanasia. My first film, Honey (2013), was about assisted suicide. At the time, everyone opposed the idea, understandably, and thought it wouldn’t be commercially viable. In Italy, as in Greece, euthanasia is illegal. Yet it’s a reality. Everyone who worked with me agreed it’s worth talking about—not just emotionally but politically. Death as a subject deeply attracts me artistically.

Why?

Dramatically, it’s a very strong theme because it’s taboo. Our relationship with death has changed. It used to be part of daily life; now, it’s rarely discussed. Yet, we see death everywhere—in movies, shows, news. We watch violent deaths almost like entertainment. We’re used to seeing people die on screen, but when it comes to acknowledging it as part of life, it becomes taboo—very personal, tender, fragile. That’s what interests me artistically. We talk about death constantly but also deny it. I fought hard to make Honey because I believe cinema must open discussions on tough topics and help change things. Maybe that’s its last real power: it can change minds.

I’ve heard many actors say they want to play a death scene. You’ve filmed many. How do you approach them?

Yes, many over the years. Some turned out very well, some less so. It’s never easy. I have death scenes in Euforia and Daughter of Mine. Each time is a new, delicate balance between truth and drama.

You prefer to ask questions and leave the audience with doubts rather than give answers. Why?

I want to show contradictions, not erase them. When you ask a question, you force the viewer to find their own answer. That’s a powerful form of communication.

Your film Daughter of Mine deals with family bonds and motherhood, exploring how it can be both tender and harsh, full of contradictions. What drew you to this?

Motherhood as an idea—not just experience—is full of clichés. I’m not a mother, but I care deeply about the image of the “good” and “bad” mother, the “right” and “wrong,” what a woman “should” feel, what it means to be a biological mother or not. These topics have been explored many times, sometimes brilliantly. But mainstream discourse—TV, melodramas, emotional rhetoric—often treats these fundamental moral issues in a judgmental way. Morality and moralizing are different things. As a director and actress, I don’t like ready-made answers. I don’t like telling people “This is how you must feel.” I prefer to ask questions and leave doubts. That’s much more interesting for me. When you ask, you make the viewer think for themselves, and that’s a powerful form of communication.

Let’s talk about L’arte della gioia (The Art of Joy), based on Goliarda Sapienza’s cult novel, which was hugely successful in Italy and led you to meet Sapienza herself in a way.

Goliarda Sapienza is a writer I deeply admire. Among other works, she wrote L’arte della gioia, now a cult classic. Recognition came after her death. I spent five years directing a six-episode miniseries based on the book, which went to Cannes and was very successful. After those years living almost inside her mind, Mario Martone asked me to play Sapienza herself in a film. So, after trying to think like her, write and direct from her voice, I was called to become her in front of the camera. It’s like her spirit is chasing me, telling me, “No, you won’t get rid of me so easily.” The film is called Fuori and I co-star with two amazing, charismatic young actresses, Matilda De Angelis and Elodie. It’s a story of a woman who wants to define her own life, body, and fate. For me, that’s deeply political.

Whenever women talk about independence, it becomes a political issue. In Per Amor Vostro, the film that earned you your second Volpi award, your character—a woman who sacrificed everything for others—says, “I was quiet all my life. Now I’ll make noise.” Why is it important to make noise today?

Something always comes from noise. We have to make noise to change things. If we stay quiet and sit in our place, nothing moves. I’m not particularly revolutionary in the stereotypical sense—I live and work within the system. But I believe you can and must say what you believe, defend what you think is right. Making noise doesn’t necessarily mean burning everything down. It means refusing to accept injustice, not saying, “That’s just how things are.” It means saying, “No, that’s not enough for me.” We won’t change the world alone, but if change happens, it’s because some people once made noise.

Ask me anything

Explore related questions