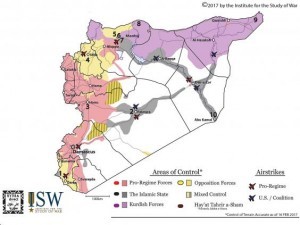

Winners and losers are emerging in what may be the final phase of the Syrian civil war as anti-Isis forces prepare for an attack aimed at capturing Raqqa, the de facto Isis capital in Syria. Kurdish-led Syrian fighters say they have seized part of the road south of Raqqa, cutting Isis off from other its territory further east.

Isis is confronting an array of enemies approaching Raqqa, but these are divided, with competing agendas and ambitions. The Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF), whose main fighting force is the Syrian Kurdish Popular Mobilisation Units (YPG), backed by the devastating firepower of the US-led air coalition, are now getting close to Raqqa and are likely to receive additional US support. The US currently has 500 Special Operations troops in north-east Syria and may move in American-operated heavy artillery to reinforce the attack on Raqqa.

This is bad news for Turkey, whose military foray into northern Syria called Operation Euphrates Shield began last August, as it is being squeezed from all sides. In particular, an elaborate political and military chess game is being played around the town of Manbij, captured by the SDF last year, with the aim of excluding Turkey, which had declared it to be its next target. The Turkish priority in Syria is to contain and if possible reduce or eliminate the power of Syrian Kurds whom Ankara sees as supporting the Kurdish insurrection in Turkey.

Turkey will find it very difficult to attack Manbij, which the SDF captured from Isis after ferocious fighting last year, because the SDF said on Sunday that it is now under the protection of the US-led coalition. Earlier last week, the Manbij Military Council appeared to have outmanoeuvred the Turks by handing over villages west of Manbij – beginning to come under attack from the Free Syrian Army (FSA) militia backed by Turkey – to the Syrian Army which is advancing from the south with Russian air support.

Isis looks as if it is coming under more military pressure than it can withstand as it faces attacks on every side though its fighters continue to resist strongly. It finally lost al-Bab, a strategically placed town north east of Aleppo, to the Turks on 23 February, but only after it had killed some 60 Turkish soldiers along with 469 FSA dead and 1,700 wounded. The long defence of al-Bab by Isis turned what had been planned as a show of strength by Turkey in northern Syria into a demonstration of weakness. The Turkish-backed FSA was unable to advance without direct support from the Turkish military and the fall of the town was so long delayed that Turkey could play only a limited role in the final battle for nearby east Aleppo in December.

Turkey had hoped that President Trump might abandon President Obama’s close cooperation with the Syrian Kurds as America’s main ally on the ground in Syria. There is little sign of this happening so far and pictures of US military vehicles entering Manbij from the east underline American determination to fend off a Turkish-Kurdish clash which would delay the offensive against Raqqa. The US has shown no objection to Syrian Army and Russian “humanitarian convoys” driving into Manbij from the south.

There are other signs that the traditional mix of rivalry and cooperation that has characterised relations between the US and Russia in Syria is shifting towards greater cooperation. The Syrian Army, with support from Russia and Hezbollah, recaptured Palmyra from Isis last Thursday with help from American air strikes. Previously, US aircraft had generally not attacked Isis when it was fighting Syrian government forces. Seizing Palmyra for the second time three months ago was the only significant advance by Isis since 2015.

Turkey could strike at Raqqa from the north, hoping to slice through Syrian Kurdish territory, but this would be a very risky venture likely to be resisted by YPG and opposed by the US and Russia. Otherwise, Turkey and the two other big supporters of the Syrian armed opposition, Saudi Arabia and Qatar, are seeing their influence over events in Syria swiftly diminish. Iran and Hezbollah of Lebanon, who were the main foreign support of President Bashar al-Assad before 2015, do not have quite same leverage in Damascus since Russian military intervention in that year.

American and British ambitions to see Mr Assad removed from power have been effectively abandoned and the Syrian government shows every sign of wanting to retake all of Syria. If Isis loses Mosul and Raqqa in the next few months there will be little left of the Caliphate declared in June 2014 as a territorial entity.

The remaining big issue still undecided in both Syria and Iraq is the future relations between the central governments in Baghdad and Damascus and their Kurdish minorities. These have become much more important as allies of the US than they were before the rise of Isis. But they may not be able to hold on to their expanded territories in post-Isis times – and in opposition to reinvigorated Syrian and Iraqi governments.

Ask me anything

Explore related questions