Nikos Marantzidis’ signature on a work of political and social history, like the newly published “Between Loyalty and Suspicion” (Alexandria Press), guarantees scientific rigor and often originality. Despite his alliance with SYRIZA (before Kasselakis) prior to the 2023 elections and his newfound admiration for Alexis Tsipras, Marantzidis continues to produce prolific scholarly work. His latest project, a collective volume, explores the bonds developed between Greek political refugees, primarily communists, and the state services of the so-called “People’s Democracies” from the end of the Civil War onwards.

Through a series of essays, the book highlights significant local differences while presenting a unified picture: Greek political refugees, expelled from their homeland after the Democratic Army’s defeat, were often treated as unwelcome outsiders in the socialist states they sought refuge in. Their expectation of finding a warm, welcoming environment proved naive and unrealistic, as they were often viewed with suspicion and treated as second-class citizens. Isolated in ghettos and under constant surveillance, their daily lives were marked by misery and distrust.

“Between Loyalty and Suspicion” focuses on the security services’ treatment of Greek refugees, both as victims and informants. It examines how these regimes encouraged refugees to spy on potential enemies or to betray their comrades.

The book “Between Loyalty and Suspicion,” edited by historian Nikos Marantzidis, is structured into seven chapters, each dedicated to a different country where Greek refugees settled after the fall of Grammos in August 1949. It covers Albania, Bulgaria, Yugoslavia (specifically the “People’s Socialist Republic of Macedonia”), Romania, Czechoslovakia, Poland, and East Germany. The Soviet Union is notably absent, possibly due to the need for more extensive analysis or insufficient information. Existing testimonies about Greek political refugees in the USSR are primarily related to the violent incidents between two KKE factions in Tashkent in September 1955.

The unique circumstances of Greek communists in each country of exile are of particular interest. As noted by philologist and author Maria Bodila in the book, “The KKE, due to specific conditions and peculiarities after 1949, created an idiosyncratic ‘country of refugees’ abroad, extending over a vast geographical area from Bulgaria to Tashkent.”

To survive, political refugees had to accept ideological subjugation, myth cultivation, and factual distortions. The party imposed a local lifestyle alien to the Greeks. Mrs. Bodilla notes that propaganda included heroic tales of workers exceeding production plans and building while tied with ropes to prevent falls.

Clandestine Operations

In Czechoslovakia, where 12,000-13,000 Greek communists lived post-conflict, refugees were surveilled, and agents and spies continued training. “Between Loyalty and Suspicion” describes a spy school operating from mid-February 1950 in Mikulovice, near the Polish border, supervised by the KKE. Trainees specialized in illegal communication, forgery, and illegal printing, with training in self-defense, making explosive devices, and operating illegal networks. Vassilis Barziotas requested further training for women to infiltrate Greek homes for espionage, but this plan was abandoned.

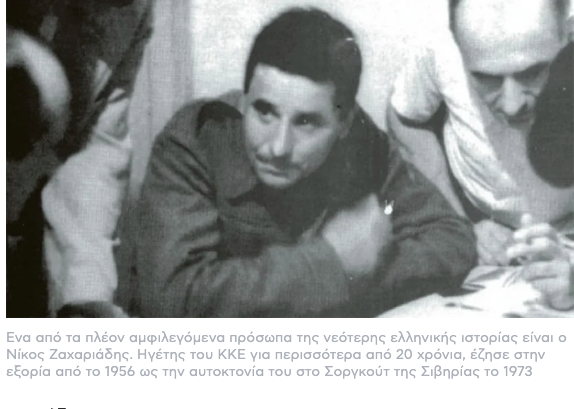

The arrest of saboteurs, the exposure of training schools in Eastern countries, and the dismantling of KKE operations in Athens, notably with the arrests of Nikos Belogiannis and Nikos Plombidis, significantly hindered Zachariadis’ envisioned partisan struggle.

The Stasi

In East Germany, the Stasi monitored the Greek community, fearing a “Trojan horse.” Greek agents helped the Stasi control political refugees, monitoring their attitudes toward the GDR, the Soviet Union, and communist ideology. Most agents were children of the Civil War, recruited in the 1960s.

The KKE’s Projects in Romania

The book notes that 65,000-70,000 Greek political refugees lived in the People’s Democracies, including 28,000 children evacuated by the KKE starting in 1948, showcasing the extensive reach of KKE’s efforts across Eastern Europe.

Ask me anything

Explore related questions